Horror from Above, As Below

A Review of Stephen Kotkin's Magnetic Mountain: Stalinism as a Civilization

Before I get going with this academic review I wrote of the Sovietologist and Stalin biographer Stephen Kotkin’s excellent Magnetic Mountain: Stalinism as a Civilization, I want to first point folks to some of the writing I have been fortunate enough to see published in other outlets in the last couple of months.

First, at one of my regular writing gigs, the classical liberal LGBT-themed publication Queer Majority released the review and analysis I did of the recent docu-miniseries on Netflix that covers the rise, fall, and rise again of the infamous actor Charlie Sheen, called aka Charlie Sheen. I was honestly shocked at how moved I was by the series, never really being a massive Charlie Sheen fan myself, but I was teleported back to the salad days of Empire, to use the Bret Easton Ellis term that was often paired with his analyses of Charlie Sheen’s antics from the time. It really shook loose the realization that the world of 2009-2012 really was a different time, not just because my generation was still finding our way in the world as post-Recession 20-somethings, but also because it somehow feels so recent until you look at a calendar. Maybe that’s just getting older.

Similarly, I was struck even harder as I read the excellent Thomas Chatterton Williams’ incredible book, Summer of Our Discontent: The Age of Certainty and Demise of Discourse. I still have many complicated feelings about the chaos of 2020, stated most often in my work here with History Impossible, but Thomas’ book really struck a chord with me. This was both in his very sharp analysis of post-2008 optimism among the young and liberal, but also how that all fell apart and ultimately became that chaos. Being from Minneapolis myself and forced to watch everything unfold from 3000 miles away in Los Angeles was always something that hit me hard, but I don’t think I ever tried to grapple with how hard it actually hit me. But Thomas’ book put me in that space, so I sat down and started to write. I wasn’t sure what it was that I had written, since it was more personal than usual, so I asked my friend David Josef Volodzko to give it a look and, if he liked it, give it a home. He was insanely generous to do so, and you can read it here, and I recommend you do if you have not already.

That is all I have in the way of updates and links to my other recent work, so I hope you have been enjoying the episodes recently released to the feed. I am currently recording and editing the next major installment of the “Muslim Nazis” series, so please stay tuned for that. Given the scope of that series, it may take a little while, so to fill the gap, I’ve been reaching out to some folks to see if I can arrange some interviews; we’ll just have to wait and see where that goes.

In any event, please enjoy this review of Stephen Kotkin’s Magnetic Mountain while you wait. It was dense, but fascinating stuff, and I am starting to finally realize that outside of American religious history, the obscure corners of World War II, and Hollywood true crime, Soviet history is becoming a growing area of interest for me.

…

The horrors of the Soviet Union, while not as well-understood or well-known as those of Nazi Germany, are well-enough-known and well-enough-understood that we can draw many associations with several images or themes. The gulag. Genocidal famine. The NKVD and KGB. Censorship, including the erasing of people from photos. The Orwellian nightmare of the Soviet Union came alive most famously from the work of Robert Conquest in which he documented the “Great Terror” of 1937, during which an estimated 700,000 to 1.2 million people were executed or allowed to starve and die of disease in the gulag system. His assessment, which seems to suggest that it was “carried out as if its scale and the identity of almost all its targets were known in advance,” was largely considered the norm in the historical scholarship.1 This created a notion of a monolith, one in which the individual human being—especially the human being living their day-to-day life in Stalin’s Russia—is immersed in the communist blob, the role of agency forgotten and the role of ideology made coarse.

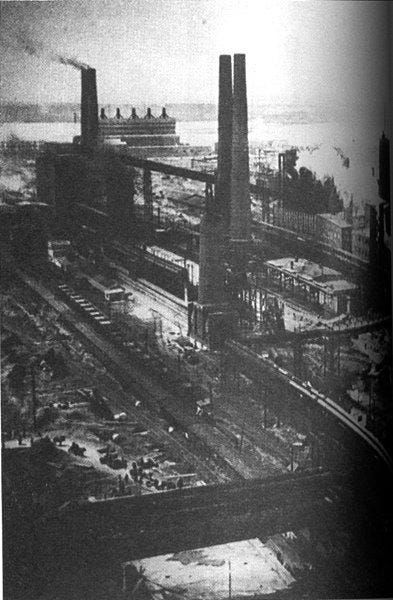

What is forgotten is that the Soviet Union, even (or especially) under the heel of Joseph Stalin from 1924 to 1953, was itself a civilization, different only in expression and kind from the capitalist norms of the West. It had its own rules, its own values, its own individuals working within it, the last of which acting as human beings as much as any American or European, and not as the automatons assumed in Western propaganda. Studying and realizing this does nothing to diminish the aforementioned horrors that existed for millions of people living within the Soviets’ grasp, but it does help illustrate the on-the-ground realities of the world’s first true, socialist civilization. That was the goal of Stephen Kotkin when he wrote his lengthy account of the industrial city Magnitogorsk’s conception, construction, and life within during the first two decades of the Soviet Union’s existence, Magnetic Mountain: Stalinism as a Civilization.

Kotkin’s central argument in Magnetic Mountain rests within the story of Magnitogorsk, but by no means is it limited to that city. As a matter of fact, for Kotkin, Magnitogorsk serves as “a microcosm of the USSR,” in which the experiences of those who built, as well as worked and lived in Magnitogorsk scaled up to how many citizens of the Soviet Union lived and how the defining feature of Stalinism—that is ideologically-motivated state building—manifested.2 As Kotkin writes, “[Stalinism] was a way of life,” in which “intricate encounters, conflicts, and negotiations […] took place in and around the strategy of state-centered social welfare in its extreme, or socialist, incarnation.”3 Stalinism, as Kotkin explains, was built on “something hopeful,” but like any system, life inside of it was “characterized by gradations of commitment—particularly in the willingness to suspend disbelief.”4 This stands in stark contrast to any notion of mindless sheep following the will of the dear leader, as is often conjured in the Western imagination when one thinks of Stalinism.

Making use of both primary and secondary sources throughout, Kotkin begins the first section of his analysis from the broadest vantage, in which he looks at the role played by economic planning in the construction of a planned community like Magnitogorsk, as well as the massive resettlement that occurred, and the creation of what would be “a recognizably socialist city.”5 Calling to mind the efforts made by the French government to essentially “civilize” their peasant population as described by Eugen Weber in Peasants into Frenchmen (as well as elements of David Blackbourn’s Conquest of Nature), the Soviets engaged in what Kotkin calls “internal colonization” of their people into “the epitome of the Bolsheviks’ commitment to massive social transformation, their martial style of economic mobilization called planning, their understanding of industrialization as class war, their yearning to overcome Russia’s historic ‘backwardness’ and to master the country’s expanse, their obsession with outracing time, and, above all, their infatuation with heavy industry.”6 His ultimate point, made even clearer in the second part of the monograph, is that a focus on Magnitogorsk offers an opportunity to scale the analysis up to the Soviet Union as a whole, thanks largely to the socialist city’s legacy as just that: an emblem of Soviet socialism.

The primary sources Kotkin uses for the first section are effective in illustrating the themes to which he has wedded his argument about Magnitogorsk. In examining the role of a planned economy, Kotkin pulls from the recollections of “a Soviet manager […] when he was upbraided by the people’s commissar” in order to get new equipment delivered to Magnitogorsk’s construction area so he could meet the deadline that was being enforced by that very commissar and others like him.7 This demonstrates, according to Kotkin, that “the establishment of a hierarchical command structure,” endemic to a planned economy, “with authoritative commanders in the field did not […] mean that all bureaucratic conflict had been eliminated.”8 A planned economy, the Soviet thinking went, did away with such inefficiencies; not so, according to the sources. Similarly, the Stalinist dream of Magnitogorsk included many promises made to the people the state imported—especially dekulakized peasants—that their work would result in proper housing against the harsh elements of the Chelyabinsk Oblast. Quoting from a heartbreaking account from “a Soviet eyewitness,” who remembered that “’it was raining, children were crying, as you walked by, you didn’t want to look,’” Kotkin demonstrates that the imported peasantry “lived initially in tents,” with thousands dying in the harsh winter.9 This was all in service to making a socialist city, or “the modern world’s first completely planned city,” which ultimately “arose largely in spite of the plans.”10 Showing the diagrams drawn by German architect Ernst May, Kotkin demonstrates how these plans were modeled after the theory of the “linear city,” and then faced several challenges that could not be easily overcome even with the power of the Soviet state.11 However, what resulted—a “part barracks settlement, part village, part labor camp and place of exile, part elite enclave, and part new city”—was “a microcosm of the Soviet Union during the building of socialism.”12 Kotkin then turns his attention away from the construction of this fully planned socialist city and then turns to what it was like to live in it, as well as the revisionism he seeks to challenge.

For part two of Magnetic Mountain, Kotkin does little to shake up his methodology when examining what it was like to live in a socialist city, using different sources to explore the housing and domesticity situation of Magnitogorsk’s people, as well as the different expressions of belief and identity, the “shadow economy” that grew from an official one without private property or freedom of commerce, and finally, the effects of the Great Terror and how “individuals came to participate in their own destruction.”13 That final chapter is where revisionism comes into play, something in which scholars like Sheila Fitzpatrick who see Kotkin’s “post-revisionism” in a more skeptical light, claiming that “Kotkin and those who followed him saw the Stalinist ideology and values [...] as a collective social construction, not something imposed by the regime.”14 Kotkin’s seeming revisionist revisionism contends a more nuanced view than is suggested there, but it only becomes clear when one examines his arguments involving living in a Stalinist civilization.

When looking at the living situation of Magnitogorsk, Kotkin makes it very clear that socialism’s “anti-world” was reflected in its rejection of capitalism as its defining feature, made most apparent by the outright non-existence of private property. Explaining that “the antagonism between socialism and capitalism […] was central [...] to the mind-set of of the 1930s that accompanied socialism’s construction and appreciation,” Kotkin explores the about-face that occurred from anti-family communalism to pro-family policies.15 This shift is explored most directly through the decree against “hooliganism” that was passed in 1935, thanks to the communal living situation faced by many families who were not happy about placing families in the same place as “’regular drinking bouts,’” and “’noise, fights, and abusive language.’”16 This, in turn, led to the adoption of policies like “private housing,” as well as more supposedly pro-family policies, like “making divorce complicated and expensive,” as well as making abortion more difficult, but ultimately, putting in place a system of mutual surveillance within the populace.17 This all revealed the further challenges in creating the perfect socialist city, showing how compromises needed to be made, and how these, in turn, produced more opportunities for state control, including via the populace themselves.

Kotkin later examines those opportunities, and the people’s ability to deceive themselves, most effectively in his discussion of “speaking Bolshevik” and how this new “anti-world” (that is, a world seemingly existing entirely in opposition to Western capitalism; i.e. a world made of “socialist competition”18), managed to form itself just as easily from below as it did from above. Using a letter sent by the wife of the allegedly best locomotive driver to the wife of the alleged worst, Kotkin shows that “the new terms of social identity were articulated and made effectual.”19 Because the latter wife was illiterate and the former was obviously not, Kotkin shows that, in an ideological sense, the people of Magnitogorsk (and the USSR in general) were creating new social hierarchies defined by the state, instead by the acquisition of wealth, seen as the default in the West. What this, in turn, supports, is Kotkin’s contention that the Stalinist world was, as Fitzpatrick noted previously “a collective social construction,” and forces him to defend his position against such revisionists.

Kotkin does so admirably when nuancing the old arguments made by Conquest, by highlighting the revisionist arguments made by the likes of J. Arch Getty and Gabor Ritterspoon. He notes that the former’s “startling and baffling conclusion” of “chaos” being “the force driving events” during the Great Terror as being derived from a “backwater” archive in Smolensk, while noting the latter’s conclusion that the Party overextended itself is “equally idiosyncratic.”20 He more than ably counteracts these old, supposedly counter-intuitive interpretations, by making use of primary source documents—namely those that explain the elaborate processes, from making steel itself to party entrance—that demonstrate anything but an atmosphere of chaos and one of complexity (which, of course, often begets dysfunction). This is to say that, despite Fitzpatrick complaining that the Soviet history revisionists had been placed in an unfair position of “the new orthodoxy,” she is right to point out that scholars like Kotkin attempted to “[impose] new rules on research methodology stressing archives and primary sources,” leading to a more cultural view of the Soviet Union during the 1930s.21 This synthetic view is what strengthens Kotkin’s overall argument better than anything else.

Kotkin does not shy away from either highlighting the Soviet Union’s horrific human rights abuses as a given, nor from pointing out that there was still a highly-functional society at the core of Stalin’s early reign, more despite the dysfunction that existed rather than because of it. It both was and was not a product of the iron will of the state, as well as the individual human responses to the events and pressures that occurred throughout the 1930s, up to and including the Great Terror. As Kotkin writes, “the Soviet regime was a dictatorship,” in which “unconditionally binding decisions backed by the threat of coercion were handed down from Moscow, without discussion beforehand and with little opportunity to give direct voice to reservations afterward.” And yet, this “realization of socialism in practice involved the participation of the people,” including attempts to “[circumvent the] official strictures” themselves.22 This does nothing to erase the horror of the Soviet Union itself, but rather, demonstrates how—like with all states, including the most heinous ones—horror is not something solely perpetuated by the state from on high. Everyone plays a part.

Bibliography:

Fitzpatrick, Sheila. “Revisionism in Soviet History.” History and Theory 46, no. 4 (December 2007), 77-91. Accessed via: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4502285.

Kotkin, Stephen. Magnetic Mountain: Stalinism as a Civilization. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press (1995).

Notes:

1. Stephen Kotkin, Magnetic Mountain: Stalinism as a Civilization (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1995), 284.

2. Ibid., 25.

3. Ibid., 23.

4. Ibid., 358.

5. Ibid., 25.

6. Ibid., 33.

7. Ibid., 418.

8. Ibid., 57.

9. Ibid., 81.

10. Ibid., 107.

11. Ibid., 110, 112-113.

12. Ibid., 144.

13. Ibid., 24.

14. Sheila Fitzpatrick, “Revisionism in Soviet History,” History and Theory 46, no. 4 (December 2007), 88.

15. Kotkin, Magnetic Mountain, 153.

16. Ibid., 175.

17. Ibid., 179.

18. Ibid., 204.

19. Ibid., 218-219.

20. Ibid., 284-285.

21. Fitzpatrick, “Revisionism in Soviet History,” 90.

22. Kotkin, Magnetic Mountain, 356.