The Fiction(s) of History

There is no progress, there are no cycles.

“We had tried every conceivable form of organization and government. We had a world in miniature. We had enacted the French revolution over again with despairing hearts instead of corpses as a result. … It appeared that it was nature’s own inherent law of diversity that had conquered us … our ‘united interests’ were directly at war with the individualities of persons and circumstances and the instinct of self-preservation.”

—Josiah Warren

“The idea of a utopian state on earth, perhaps modeled on some heavenly ideal, is very hard to efface and has led people to commit terrible crimes in the name of the ideal.”

—Christopher Hitchens

“‘Deserve’s got nothin’ to do with it,’ as Will Munny wisely observed [in the film Unforgiven]. Sometimes the good guys win, sometimes they don’t, and sometimes (maybe most of the time) there aren’t any good guys. And a lot of it’s just chaos and statistics.”

—CJ Killmer, The Dangerous History Podcast

…

Bari Weiss’ excellent Free Press publication put out an even more excellent piece written by essayist and literary critic William Deresiewicz essentially explaining how the idea of “the right side of history” is a complete myth. I highly recommend you check it out, perhaps before diving into this “yes, and” I’m here to provide, because it prompted me to finally put pen to paper (or, well, fingers to keyboard, voice to mic) to explore something I’ve touched on with some depth before in History Impossible—specifically my episode concerning Savitri Devi, Hitler’s Hindu priestess. That is, more broadly, the view of history, both from a progressive and a cyclical perspective. To put it bluntly, these are fictions: history, in my view, has no arc—there is no progress and there are no repeating cycles. And even though I’ve discussed this before, I really wanted to dive in and explore it.

Much of what I ultimately believe about history is, perhaps to the jaundiced eye, rooted in pedantry; I will be the first to admit it. But what are history fans, if not extremely pedantic? Just spend an afternoon browsing the various subreddits dedicated to history, especially including the famous r/AskHistorians, and you’ll see exactly what I mean. This isn’t to say these things don’t matter, however; in our current age of political pontificating and mineral extraction-esque mining of the world for outrage, much of what animates these discussions is a notion of human progress or a notion of returning to an earlier place in our historical cycles. Whether these animating forces are conscious or not is largely irrelevant since, either way, it is, at best, alienating to see your view as being one of a righteous march toward the ideal future or the righteous return to a noble past. At worst, it’s beyond destructive.

So to begin, let’s look at the prevailing notion of historical progress.

The Rubber Band of Justice

When we were kids, a lot of us—well, okay, I—used to play with rubber bands by stretching them as much as possible. This was usually done to shoot the rubber band like an annoying projectile at your friends and classmates (or perhaps a girl you liked; I know, boys are dumb). The thing is, there was always a non-zero chance that the rubber band was likely to snap back and sting your fingers. You still could have shot the rubber band effectively, but it wouldn’t have stung so much when it snapped back and lashed your fingers if you hadn’t been so overzealous in pulling it back as far as it would go. This is not even to mention that if the rubber band was old or not very good quality, then the entire thing could just snap in half. This phenomenon is actually rooted in basic physics: the law of conservation of energy, which states that energy can neither be created nor destroyed—it’s simply converted into another form of energy.

This perhaps-strained metaphor can help illustrate the fundamental problem at root when one believes that history’s arc bends toward justice, i.e. progress. This has been seen most pointedly in the fundamental assumptions—what few conscious ones there are—at the root of what we’ll call “critical social justice” (CSJ), though what many refer to derisively as “wokeness” or, if we really want to use a throwback, the ideology of “social justice warriors” (SJWs). Regardless, it is the current cause du jour among politically progressive-minded people in the West in general, and in the United States in particular. And while many aspects of this way of thinking—that the United States is, to this day, a deeply White Supremacist, Patriarchal, and Hopelessly Bigoted place to live if you experience Unequal Outcomes—are simply hyperbolic, essentialist, and above all, STUPID theses, the true error found within them is the core assumption required to believe them (never mind the cynics among us who see financial sense in adhering to these social principles): that the moral arc of history bends toward justice, that we are, of course, all progressing toward something much better for everyone and that anyone who opposes it is a moral pervert. Crucially to this Manichean worldview, however (apart from a flawed belief in notions of “human progress”), is the part that is often said with ever-increasing ferocity: that those who don’t fall in line will be “left behind” (though perhaps ironically, those who believe that always seem intent on doing all they can to not leave the supposed “holdouts” alone). While the damage caused by the proverbial snap-back of the proverbial rubber band is certainly worth being concerned about—because that does often happen—there’s something more fundamentally wrong with this assumption of human progress that goes far deeper, and is worth examining.

There is the old saying (whose core truth was unfortunately abused frequently throughout the 2000s during the peak years of America’s War on Terror) that “one man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter.” One could also say, with just as much reason, that one person’s progress is simply another person’s tyranny. One can already hear the protestations that this kind of attitude enables the subjugation of oppressed peoples—like the Jews in Nazi-occupied Europe in the mid-20th century, or the enslavement of African-descended Americans in the 18th and 19th. This might seem like a rhetorical/historical slam dunk, but it manages to miss a profound difference between the pursuit of (critical social) justice in the 21st century and the injustices of the 20th, 19th, and 18th: namely that in those injustices—that of slavery and genocide—the subjugation and destruction of the disenfranchised was the point. The supposed inequities/indignities of the 21st century, no matter how you spin them, are not being done for their own sake (if they’re even being done at all); if that were the case, our legal framework would be contracting and doing so rapidly and broadly, not expanding and doing so rapidly and broadly in ways unthinkable less than even 20 years ago. Far be it from me to be so cynical (lol), but when weighing the evidence available, I think it’s less likely that American society still needs to progress toward a more equitable, free future, and more likely that sociopolitical ambulance chasers (or people afflicted with “hero syndrome”) are invested in assuming that the world is more broken than it actually is so they have something to fix and, thus, meaning in their lives.

However, to claim that notions of “human progress” are just rooted in magical thinking and leaving it at that simply won’t do for our purposes. This is why it’s important to turn to history and assess the track record of assumptions of “human progress.” To do this, I want to highlight three different-but-related stories that stretch across two continents and three cultures over the course of a little less than a century. After this, I hope that you, dear skeptical reader, will understand at least where I’m coming from when you protest and tell me notions of human progress are “all we have” in our godless, uncaring world.

…

As Edwin Black writes in his book The War Against the Weak, “America was ready for eugenics before eugenics was ready for America.” To put it bluntly, as Black does, “breeding was in America’s blood,” as made apparent by the centrality of “good breeding” in the so-called peculiar institution of slavery. After all, “slavery thrived on human breeding,” Black explains. “Only the heartiest Africans could endure the cruel middle passage to North America. Once offloaded, the surviving Africans were paraded atop auction stages for inspection of their physical traits.” This story is familiar territory for most students of American history, of course, but there’s something to highlight about this: it’s that Americans—especially its elites—were already primed for seeing fellow human beings as something to be molded by selective breeding, little different from common livestock. This was why eugenics was so readily seen as acceptable in the minds of many Americans—including those who might have balked at slavery’s abject immorality—later in the 19th century. It wasn’t the perception of African slaves as livestock (or even the underlying racist perceptions that fueled such a thing) that was the problem for many Americans; it was the cruel treatment they received while acting as livestock (e.g. being whipped, raped, or lynched). While there were certainly plenty of Americans who saw the brutal and inhuman truth of slavery, many simply wanted to live in a world where face could be saved; the institution of slavery was, especially in the “civilized” European world, unfashionable by the time Americans did away with it.

So when books and papers like Francis Galton’s Hereditary Genius: An Inquiry Into Its Laws and Consequences in 1869, or Richard Dugdale’s The Jukes, a Study in Crime, Pauperism, Disease and Heredity in 1877, or Reverend Oscar McCulloch’s Tribe of Ishmael: A Study of Social Degeneration in 1888, or, perhaps the most infamous of them all, Madison Grant’s The Passing of the Great Race: Or, The Racial Basis of European History in 1916, it’s hardly a surprise they were all hits, especially among the intelligentsia of the time. This intelligentsia—both then, and today—was defined by their notions of human progress and were thus called “progressive” in every sense of the word, all cloaked in the language of charity and compassion. As Edwin Black writes in War Against the Weak:

“Many leading social progressives devoted to charity and reform [in the late 19th century] saw crime and poverty as inherited defects that needed to be halted for society’s sake. When this idea was combined with the widespread racism, class prejudice, and ethnic hatred that already existed among the turn-of-the-century intelligentsia—and was then juxtaposed with the economic costs to society—it created a fertile reception for the infant field of eugenics. Reformers possessed an ingrained sense that “good Americans” could be bred like good racehorses.”

While of course this was written by Edwin Black with the benefit of hindsight, it is by no means an exaggeration. The forefather of this “infant field,” Francis Galton, put it most plainly towards the end of his infamous work Hereditary Genius, laying out what he saw as the inherent good of such a project (one that he would indeed coin as “eugenics” in his 1883 work, Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development). Galton wrote the following:

“The best form of civilization in respect to the improvement of the race, would be one in which society was not costly; where incomes were chiefly derived from professional sources, and not much through inheritance; where every lad had a chance of showing his abilities, and, if highly gifted, was enabled to achieve a first-class education and entrance into professional life, by the liberal help of the exhibitions and scholarships which he had gained in his early youth; where marriage was held in as high honor as in ancient Jewish times; where the pride of race was encouraged […] where the weak could find a welcome and a refuge in celibate monasteries or sisterhoods, and lastly, where the better sort of emigrants and refugees from other lands were invited and welcomed, and their descendants naturalized.”

While eugenics increasingly took up what could best be described as an irrational defensive structure—particularly with early 20th century eugenics enthusiasts like Madison Grant and Lothrop Stoddard, the latter of whom wrote a book called The Rising Tide of Color Against White World Supremacy in 1920—eugenics was not initially an inherently reactionary movement for the time. We may see it that way today—and correctly so—but at the time of its popularity (which lasted far longer than many realize, with the American Eugenics Society existing by that name until 1972; and fan fact, following the passage of Roe v. Wade in 1973, they renamed into the much-more-PC The Society for the Study of Social Biology, which exists to this day under its third name, the Society for Biodemography and Social Biology), it was the cutting edge. And, as you likely picked up from the previous quotes, it was also seen as compassionate route to take: both for those “afflicted” and for those of “good stock.” If society wished to progress, as the thinking went, then it would be necessary to weed out the undesirable traits—i.e., people who carry those “bad” traits—and allow the strongest—i.e., people who carry the “good” traits—to survive and thrive. Of course, there are indeed traits that are undesirable—extreme conditions such as anencephaly come to mind—and by no means is this to say that abortion is “just” eugenics; in the most technical sense I suppose it meets the definitional criteria—you are indeed culling potential offspring—but as best I can tell, it is rarely (anymore), if ever done with engineering a master race in mind. However, the definition of “undesirable traits,” especially in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, is about as mushy as notions of “progress.” We need only look at the story of Carrie Buck.

In 1924, 18-year-old Carrie Buck was deemed “feebleminded” (as well as having “incorrigible behavior” and “promiscuity” because of course she was) by a Virginia judge after she accused a member of her adopted family, the Dobbses, of raping her, leading to impregnation. She had no known mental conditions, much less what today we’d call a developmental disorder, but was nevertheless committed to the Virginia Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded, alongside many other women—including her own mother, who had been committed there for her own “feeblemindedness,” which had lead to Carrie being placed in the care of the Dobbs family, whose parents’ nephew was ultimately revealed to be her rapist. Carrie ultimately gave birth to her child who, despite being without her mother and stuck with the same Dobbs family, showed herself to be anything but “feebleminded” when she scored well on all her school subjects except mathematics. Unfortunately, Carrie’s daughter—named Vivian—contracted measles in 1932 and died at the age of eight, while her mother continued to be confined in the Colony. But Carrie’s suffering didn’t end with losing her child or merely being imprisoned in a place for unwanted women, which was becoming, as Edwin Black puts it, “a dumping ground for those deemed morally unsuitable.” The Colony’s superintendent, Dr. Albert Priddy, would write in his 1923 Biennial Report, using very familiar eugenic language that focused on the sake of wider society’s health, the following recommendation regarding the growing population of “immoral” and “feebleminded” inmates:

“If the present tendency to place and keep under custodial care in state institutions all females who have become incorrigibly immoral [continues], it will soon become a burden much greater than the state can carry. These women are never reformed in heart and mind because they are defectives from the standpoint of intellect and moral conception and should always have the supervision by officers of the law and properly appointed custodians.”

Concluding, Priddy recommended the implementation of surgical sterilization. And shocking as it may be to hear to us today, this “remedy” was enthusiastically supported—both by the elites of society and by the experts in whom they placed their trust. As Dr. H.E. Jordan, Dean of the Department of Medicine at the University of Virginia, put it, “eugenics… will work the greatest social revolution the world has yet known… [for] it aims at the production and the exclusive prevalency of the highest type of physical, intellectual, and moral man within the limits of human protoplasm.”

Sterilization was thus on the table. And Carrie Buck would be, as Edwin Black put it, “the test case.”

Despite attempting to fight against her imminent sterilization all the way up to the Supreme Court, Carrie Buck, with the permission of the SCOTUS, was sterilized on October 19th, 1927, receiving a tubal ligation (i.e. “tube-tying”). She was the first, but she would not be the last, with 12,000 other Americans being sterilized in over two dozen other states that had legalized the practice until 1947 (and over 70,000 in total while it was still being practiced). This included Carrie’s sister Doris, who was sterilized against her will while undergoing treatment for appendicitis shortly afterward. It was all done for the “health of the state”; i.e. for the sake of societal “progress.” As Chief Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes put it in his ruling on the Buck case:

“We have seen more than once that the public welfare may call upon the best citizens for their lives. It would be strange if it could not call upon those who already sap the strength of the State for these lesser sacrifices, often not felt to be such by those concerned, in order to prevent our being swamped with incompetence. It is better for all the world, if instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime, or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind. The principle that sustains compulsory vaccination is broad enough to cover cutting the Fallopian tubes. [...] Three generations of imbeciles are enough.”

While it’s doubtful many Americans would even care had they known, little did they know where these medicalized notions of “progress” would be taken across the Atlantic Ocean only a handful of years later.

…

In Mein Kampf, Adolf Hitler wrote the following:

“Anyone who wants to cure this era, which is inwardly sick and rotten, must first of all summon up the courage to make clear the causes of the disease.”

It’s clear that Hitler’s medicalized rhetoric when it came to what he saw as the undesirable elements of German society—he once said “I discovered the Jew as the bacillus and fermenting agent of all social decomposition”—was rooted in defensive language. He frequently invoked “cleansing” metaphors, demanding that Germans undergo an improvement of their “Rassenhygeine,” excising the “unclean” parts of their society so that it may “return” to its earlier, cleaner state. Despite being a known and tactical liar, it’s highly unlikely that Hitler disbelieved anything he was saying in this regard—he did likely believe he was defending the “cleanliness” of the German race from contamination. And yet, the closer we start looking at the Nazis’ activities beyond “simply” the mass killing—the activity that was firmly rooted in Hitler’s delusions of erecting a “defense” against his so-called “bacillus”—a familiar picture does indeed start to form, particularly in the actions of the infamous “Nazi doctors,” as psychologist Robert Jay Lifton termed them.

This might not seem like it relates much to the idea of human progress, especially since as we’ve covered in History Impossible, many of the core Nazi elites—including Hitler to an extent—were animated by notions of cyclic time. However, it’s important to note that although the Nazis were indeed pumped up on a notion that they were ultimately returning to a glorious, ancient past—that of Aryan dominion—Hitler saw this cyclic return as part of human progress. Hitler made this very clear whenever he invoked the notion that conflict between the different races was the source of human progress; his view was simply that there would be progress for some and not for others. This is why strengthening the German people—the Volk—became paramount. However, in order to do this, the defensive measures first had to be undertaken, in which the very eugenics programs pioneered the previous decade in the United States were taken to their cruel, logical conclusion.

Before World War II even began, the Nazis had sterilized 95% of an estimated 400,000 people deemed undesirable within their borders. They used the methods preferred by American eugenicists—namely vasectomies and tubal ligations—but they went even further and experimented with the use of chemical castration and even radiation treatments. Almost half of these sterilizations were, like the United States’ own sterilizations, due to purported “feeblemindedness,” but it soon became clear—at least in the ideologically-possessed minds of the Nazis—that sterilization would not be enough to promote the creation of the idealized Aryan race. This was where euthanasia entered the picture. As Dr. Alfred Pasternak explains in his book Inhuman Research: Medical Experiments in German Concentration Camps:

“Doctors and other leaders simply had to have the ‘courage,’ as Hitler put it in Mein Kampf, to do the job, however distasteful or immoral it might seem. […] The Nazis grounded their arguments for euthanasia on two assumptions: first, that human beings are not biologically equal; and second, that this inequality relieves the State of the duty to protect all its citizens: the weak can be sacrificed. Euthanasia was simply one way of putting these assumptions into practice.”

Despite the difference in outcome—i.e. sterilization instead of outright euthanasia—this was the exact same motivation that drove the eugenics programs in the United States—to weed out the undesirable and promote the replication of the desirable. And indeed, it’s well-trod territory (at least with History Impossible) that the Nazis were very much inspired in their programmatic racism by American eugenic progressives like Madison Grant, who, if you’ll recall, corresponded with Hitler and whose book, The Passing of the Great Race, Hitler anointed as “my Bible.” Consider this further explanation by Dr. Pasternak, where the quotes might sound eerily similar to what was written in the report given by Dr. Albert Priddy when explaining the need for a sterilization program for the feebleminded and immoral:

“These ideas had been spelled out in 1920 in the book Die Freigabe der Vernichtung lebensunwerten Lebens [The Permission to Destroy Life Unworthy of Life], by two eminent German professors, Karl Binding, a legal authority, and Alfred Hoche, a professor of psychiatry. Binding and Hoche demonstrated that ‘assisted death’ could be justified on medical and legal grounds. Their argument was primarily utilitarian in nature: putting people to death can be a ‘useful act’ because it relieves individuals and the State of the tremendous economic burdens associated with caring for the incurably ill, the feebleminded, the retarded, and the deformed. The phrase ‘lebensunwerten Lebens’ [life unworthy of life] passed into the German lexicon as a respectable concept, which Hitler embraced and which, under the Nazis, acted as a euphemism signifying all people who did not meet the Nazis’ criteria for membership in the master race.”

We know where this ultimately lead. Mass culling, however politically-motivated, was always done under the justification of “cleansing” the new German Reich of tainted blood. This cleansing, however, was only half of the equation. Not only must the undesirable elements tainting society be removed, but a strengthening of the German race so that they could be the strongest people with the purest racial stock on the planet must be undertaken. There is a perverse irony that I may have mentioned on the podcast before that despite doing all they could to dehumanize the Jews and their other victims, the Nazis made it a point to use them as human guinea pigs in various experiments, after which, pending positive results, treatments would be developed for the German Volk. The experiments on concentration camp inmates involved the deliberate infection of diseases like typhus, malaria, and tuberculosis were not simply conducted for the sake of “mere” cruelty—though they obviously were cruel in spades—but for the sake of trying to create treatments. The same goes for their hypothermia treatments at Dachau, which, disturbingly, have been cited positively in certain medical circles, and did indeed produce “valuable,” if still very morally tainted, data. Experiments involving phosphorus burns, exposure to mustard gas, and forcing seawater into the victims’ stomachs were also conducted, also all for the sake of “improving” lives, though whose lives were being improved were always understood to be the pure German ones set to inherit the earth. This was “medical progress” at its most perverse.

However, the most apparent use of medical science for the purposes of “progressing” the Aryan people comes from one of the most infamous Nazis of all, Auschwitz’s Dr. Josef Mengele. While some have presented reasonable arguments that Mengele was a true psychopath who simply enjoyed causing human suffering for its own sake, it may be a mistake to believe that he wasn’t pursuing certain, ideologically-driven ends with some of his experiments, particularly those that involved twins. However insane it indeed was, Mengele was ostensibly trying to learn how he could genetically engineer the Aryan master race by studying identical twins—normally a perfectly reasonable vector for studying genetic inheritance. Supposedly in attempting to discern these traits, he engaged in everything from daily blood drawings and anatomical examinations to far more brutal experimentation. This included administering eye drops or even chemical injections into the eyes in order to make them turn blue (which was often painful and resulted in permanent blindness), as well as amputations of the hands and removal of the organs (sometimes done without anesthesia). This was always done because one twin could be used as a control and the other as the experiment; this was most overtly seen in the deliberate infection of diseases like typhus into one twin, whose inevitable death was followed by the murder of the other twin so both bodies could be examined. While it’s hard to imagine any scientific validity behind such experiments, even in trying to discern environmental pressures from genetic ones by using twins, it wasn’t hard for Mengele to justify what he was doing. According to Dr. Miklos Nyiszli, a Jewish doctor pressed into Mengele’s service in exchange for his family’s safety and, more importantly, the primary eyewitness of Mengele’s work at Auschwitz, Mengele was attempting to “establish a genetic cause for the birth of twins in order to facilitate the formulation of a program for doubling the birthrate of the ‘Aryan’ race” (per the Encyclopedia of the Holocaust).

While it’s certainly reasonable to assume this was just a front for Mengele’s own twisted peccadilloes (and many of his experiments and actions I have, to be frank, mercifully left out of this account certainly suggest little more than that), it’s also a mistake to think that this kind of effort to literally breed Aryans (while culling the Jews and other “undesirables” from the German stock) was a one-off. While Mengele was supposedly attempting to “scientifically” double the birth rate of Aryans, our favorite Nazi ideologue on History Impossible, Heinrich Himmler, had been busy with one of his many pet projects, this one being known as the Lebensborn (or “Fount of Life”) association. In this “august” organization under the purview of the SS, “pure” German parentage was encouraged, in which the offspring of a German couple—married or otherwise, oftentimes not—was deemed “racially valuable.” If a woman gave birth to enough “racially valuable” offspring, she would be awarded the Cross of Honor of the German Mother for being so dedicated to creating a vast Volk. This program quickly went international as the years went by, with locations cropping up in all European nations deemed to have appropriate numbers of Germanic people (namely places like Norway) in order to help bolster the numbers. Ultimately, tens of thousands of German children were conceived this way, with many others even being kidnapped from other countries in order to be raised in Germany as Germans.

Whether or not it was always overtly the case, the base justification for all of these things was simple: strengthening the German race so it could never again be “weakened” by the undesirable elements currently being cleansed away. There’s simply no other way to characterize it: it was a medicalized program of human “progress,” writ as large as could be. And yet, attempts at “progressing” the human race, kicking and screaming, wouldn’t die with Hitler and the Nazis. In a lot of ways, such attempts to push the human race forward in the most brutal ways imaginable had just begun.

…

If you’ll allow me a brief moment to vent, there is far too much debate on the question of whether or the Nazis or the Soviets were evil. The numbers game is frequently invoked—Hitler’s dozen million versus Stalin’s purported two dozen million—which almost always falls mightily short of an incisive analysis and becomes your run of the mill ideological pissing contest, as I’m sure I’ve said here before. I’m still woefully uneducated regarding the history of Soviet Russia, at least compared to how much I know about the Third Reich, but from what I do know, I think the best way to describe Stalinist Russia—especially post-World War II—is to say that the Soviets looked at the kinds of experimentation the Nazis conducted and decided to say, “yes, and,” like an eager student at Second City. There is no sordid tale better suited for illustrating this than that of the “reeducation” experiments conducted at Pitești Prison in Romania between 1949 and 1951.

I know I share a lot of readers and listeners with Darryl Cooper of the excellent MartyrMade podcast, so many of you have likely already delved into all of his content, but for those who haven’t—and for those who have a strong constitution—I need to recommend you give his 4-hour episode “The Anti-Humans” a listen to get the full picture of the story I’m about to tell you. This story is far lesser-known than the stories of the Holocaust or perhaps even the stories of American eugenics, at least outside of Soviet history circles. But much of what you’ll be reading here will sound very familiar, either from reading classic works of literature like 1984 (or, frankly, the Marquis de Sade) or from seeing classic art house cinema like Salo: 120 Days of Sodom. It’s ugly. Indeed, famed anti-Soviet dissident Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn called it “the most terrible act of barbarism in the contemporary world.”

Shortly after the formation of the Socialist Republic of Romania in 1947, Pitești Prison became a site of what the Romanian literary critic and journalist Virgil Ierunca described as the largest brainwashing program in the entire Eastern Bloc of post-war Europe, with anywhere from 780 to 5,000 people subjected to the experiment during its two years of operation. Similar to the seeming nihilism of Dr. Mengele’s experiments, it’s at first hard to process what “use” the experiments conducted on the inmates at Pitești could possibly have, but unlike Mengele’s twisted experiments and surgeries, the Pitești experiments weren’t done with killing the prisoners (or rather, “subjects”) in mind. Operating from the basis of Stalinist state atheism—a sickening use of the term and even more sickening use of non-theistic belief, but it is what it is—the Romanian government wanted to see if it was possible to literally purge the brain of past religious or ideological convictions that ran counter to communist ideology, replace them with new beliefs, and eventually, rewrite the personality of the person whose mind had been purged: in essence, undo their personalities to allow them to progress from their supposedly backward religious beliefs and develop a true “communist personality,” according to Roman Braga, a friar who survived the gulags. Needless to say, it destroyed the subjects from the inside out.

This type of brainwashing-through-torture has been the subject of everything from The Manchurian Candidate to an excellent episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation, and even though I think George Orwell’s 1984 comes pretty close to depicting the sort of mind-replacing torture seemingly so common behind the Iron Curtain, none of these depictions even approaches the depravity visited upon the young people—many of whom were sincere adherents to the Romanian Orthodox Church, including actual seminarians and university students—at Pitești Prison. The Romanian author Dumitru Bacu, whose 1963 book The Anti-Humans: Student Re-Education in Romanian Prisons documents the tortures the people interned at Pitești Prison, described the program as follows:

“Everything of the past which could offer any kind of refuge was to be muddied and denigrated. This included the heroes of history and the folklore of Christian inspiration. Then, to be given special attention, was the destruction of love for family, in order completely to isolate the victim in his own misery, bereft of religion, love of country, and family. This would break the chain that links together a community of national thought and gives meaning to a national struggle. When the individual was thus cut off from his history, faith and family, the ultimate step in ‘re-educating’ him was to destroy his existence as a personality – an individual. This, to the victim, was to prove the most painful step of all and was called his ‘unmasking.’”

“Unmasking” was the ultimate goal; once the prisoner was “unmasked,” the remolding of his mind could begin. The path to unmasking was beyond brutal and depraved, and separated into three distinct stages. During the first stage, the prisoners were frequently beaten and tortured while being strenuously interrogated about past sins, many of which were completely fabricated by the prisoners in efforts to stop the pain. The second stage, which was termed “internal unmasking,” the prisoners were encouraged to essentially rat out other prisoners who were supposedly less committed than them to the reeducation process, essentially isolating them from one another. And finally, in the third stage, the prisoners were forced to publicly renounce all previous ties to faith, ideology, and even friends and family. According to Virgil Ierunca, this was all done repeatedly and perversely, with forced blasphemy playing a large role in the programming (including perverse rituals laced with Christian symbolism being paired with forced sexual degredation between the inmates). Other negative associations with Christian belief and practice were created, with the guards using buckets of urine and shit, both as sacraments, and as methods of drowning torture. Such torture was also done to extract false confessions from the prisoners regarding their families and friends, as well as rewriting the prisoners’ own personal histories, so they would naturally feel like they had nowhere else to turn but toward their new futures, molded by communist doctrine.

Similar to how most communist regimes handle disaster, the actual people responsible for allowing such an experiment to happen were never found responsible and instead, the flunkies—no less innocent by any means—were scapegoated, with over 20 people who participated in the experiment—namely inmates who had turned on the other prisoners—executed by firing squad in 1954 after it became clear what had been going on at Pitești. And indeed, the members of the Romanian secret police, the Securitate, who oversaw the experiment, were all given light prison sentences, and the entire project was claimed by the courts to be the product of American and fascist agents who had infiltrated the Securitate.

The Pitești Prison experiments were more than just the obscene depravity dreamt up by a communist regime possessed by runaway Marxist dogma in the mid-20th century (which, frankly, simply smacks of simplistic ideological analysis). More to the point, it shows what lengths people may take to both unmake (or “unmask”) a person and then, thus, remake them in a newer, “better” image. It, like the other stories I’ve related here, shows what lengths people possessed with illusions of human progress will take to get us to a supposedly better future, the corpses and shattered souls left in that future’s wake be damned.

…

This might seem like a silly question—perhaps an all-too-simple one—but it must be asked: in this historical context, just what is progress? To what are those who champion “progress” purporting to aim? As the philosopher John Gray wrote, “Modern politics is a chapter in the history of religion.” What we know about religion is that, whether it promises a blissful continuation life after worldly death or an enlightened way of Seeing the World, it purports to provide our species a world without the ever-present existence of that thing no one has ever truly escaped: suffering. In other words, progress promises utopia. And if you know me, ladies and gentlemen (brothers and sisters, comrades and friends), you know that I possess an inherent distrust (and some might even say disgust) with the idea of utopia. In his excellent book Black Mass: Apocalyptic Religion and the Death of Utopia, John Gray provides a nice analysis of the very modern propensity, especially in the West, to look at history as a linear line moving from depraved anarchy toward civilized Utopia:

“[T]he myth that humanity is moving towards adopting the same values and institutions remains embedded in Western consciousness. It is a belief that has been defended in many theories of modernization, but it is instructive to recall the many incompatible forms this ultimate convergence has been expected to take. Marx was certain it would end in communism, Herbert Spencer and F.A. Hayek that its terminus would be the global free market, Auguste Comte was for universal technocracy and Francis Fukuyama ‘global democratic capitalism’. None of these end-points was reached, but that has not dented the certainty that some version of Western institutions will eventually be accepted everywhere—indeed, with every historical refutation it is more adamantly asserted. The communist collapse was a decisive falsification of historical teleology, but it was followed by another version of the same belief that history is moving towards a species-wide civilization.”

Gray also asserted in his 2007 book that faith in utopia is dead, but I’m inclined to disagree, precisely because of this faith in human progress that he so astutely outlined. To believe in progress is to believe in some sort of universally appealing destination, even if it’s claimed—and it often is—that progress is its own reward and keeps us going; that it’s “all we have,” in other words. This may seem pedantic—and more on that later—but what that describes is a process, not progress. Processes require objectives, but they don’t require moral assumptions. Progress does.

When it comes down to it, progress is a moral assumption about the passage of time and what occurs within that passage. There is technological progress and increased legal protections, to be sure, and those can and should be celebrated where appropriate. But the people who want to believe that human progress is a tangible and thus inevitable are just going to end up with two possible choices: forcing the issue as American eugenicists and the Nazi racial scientists and the Soviet psychological torturers did, dragging society kicking and screaming and causing untold levels of suffering, or letting go of that rubber band. And wouldn’t it be preferable if that rubber band hasn’t been getting stretched to its very limit before it snaps back? Wouldn’t it be preferable if the snap back was eased, rather than simply released?

Cyclical Determinism

In their famous 1997 book The Fourth Turning, authors William Strauss and Neil Howe wrote that “Sometime around the year 2005, perhaps a few years before or after, America will enter the Fourth Turning.” (Emphasis added). Following this proclamation, Strauss and Howe provide some potential examples for what the Crisis—that is, the catalyst for the so-called Fourth Turning—might be, including:

A fiscal crisis.

A terrorist attack.

Congressional shutdowns.

A new pandemic.

A war started by Russia.

Likely any and all of these predictions strike a chord with those of you reading, especially if you’ve paid attention to current events during the last decade or so (with the terrorist attack of course invoking memories of 9/11 in Americans). All of these predictions made in 1997 have, in essence, been “confirmed.” The reason for so many people who have read this book—including the infamous Steve Bannon—believe that Strauss and Howe have identified the patterns that underlie the United States’ history and, more importantly, future, is because of these “confirmations.” It’s truly captivating to feel like someone has the future figured out. After all, the ability to predict the future is on the level of the ability to know what happens after we die or the ability to live forever, in terms of miracle wishes that defy the laws of existence. And at initial glance, Strauss and Howe present a compelling thesis: that history—Anglo-American history in particular—operates in century-long cycles in which exist four “turnings,” or new eras. As they write early on in their book:

“Over the past five centuries, Anglo-American society has entered a new era—a new turning—every two decades or so. At the start of each turning, people change how they feel about themselves, the culture, the nation, and the future. Turnings come in cycles of four. Each cycle spans the length of a human life, roughly 80 to 100 years, a unit of time the ancients called the saeculum. Together, the four turnings of the saeculum comprise history’s seasonal rhythm of growth, maturation, entropy, and destruction.”

If this is sounding familiar to History Impossible listeners, it should: this is the exact same structure of the Hindu cycle of the ages, or the time cycle, that we discussed in the episode in which I covered Savitri Devi and the most esoteric elements of the Nazi ideological worldview. Some of this is will cover the same ideas and material, but it’s a subject I find so interesting—that is, the belief in historical cycles—that I feel like it’s worth fleshing out a little bit. And in this case, we’re zeroing in on the more modern, Western incarnations of the subject of historical cycles that I mentioned more in passing in that episode. But they’re no less important to my—spoiler alert—skepticism toward and even dismissiveness of historical cycles that approaches the same tenor as that which I have for progressive views of history. And you can’t discuss modern Western notions of historical cycles without discussing the ideas contained within Strauss and Howe’s popular book.

As Strauss and Howe explained, the four turnings are characterized by “growth, maturation, entropy, and destruction.” The First Turning is sparked by a “High,” where individualism is on the back foot, institutions are strong, and there is a new, robust civic order; this was the 1945-1963 years. The Second Turning is sparked by an “Awakening,” in which “spiritual upheaval” occurs and new values are thrust upon the formerly robust civic order; this was the Baby Boomers coming of age in the late 60s and early 70s leading into the Reagan Revolution. The Third Turning is sparked by an “Unraveling,” in which, well, things unravel: the civic order is no longer robust, people begin to atomize with thriving individualism, and the values introduced during the Awakening begin to replace the formerly robust ones; this was the millennial years, defined by Clintonian neoliberalism and, as it would turn out, the War on Terror. And finally the Fourth Turning—which marks the Kali Yuga in the Hindu time cycle—is sparked by a “Crisis,” in which we live through “a decisive era of secular upheaval, when the values regime propels the replacement of the old civic order with a new one,” as Strauss and Howe put it; this would be the post-Great Recession, post-COVID, post-Russo-Ukrainian War world, according to adherents to this historical hypothesis.

This hypothesis is certainly compelling enough to explore—and I must shout out my comrade Darryl Cooper for recently doing so on his own Substack, which is worth checking out for some more detail on this. As I said in a comment there and as I’ve said elsewhere, the Strauss-Howe generational theory of history (as it’s more widely known) is a great place to start: it’s a compelling thesis and, thanks to its looseness, is something that can be tested if you’re able to nail down concrete variables. However, that looseness is exactly why I find The Fourth Turning—and by extension, other cyclical theories—so frustrating in broad terms. Namely, that it’s incredibly easy to lay out those previous five examples of crises for almost any period in history, simply adjusting the few specifics that are present within the predictions. Congressional shutdowns are a feature of political polarization which tends to concentrate in particular historical moments, but it’s by no means confined to 20-year chunks of time. Terrorism has been a “normal” activity of political radicals since the 19th century, perhaps earlier. Financial crises are a dime a dozen, some worse than others. The same can easily be said about war. And disease is a constant feature of not just the human experience, but the experience of all life on earth. When you take this into consideration before looking at the various world events of the last decade and a half or so, you start to realize that it’s very easy to essentially glue these predictions onto those world events thanks to hindsight. What I’m describing, put simply, is known as confirmation bias.

This isn’t to say it isn’t fun to point out the seeming accuracy of the claims made by Strauss and Howe; it’s fun the way astrology can be really fun, or sleight-of-hand magic, or rapid-fire impressions of celebrities. In other words, it’s great for dinner parties. But it is to say that it becomes very tempting to see capital-T Truth in such claims when they seem to match up with our own lived experiences. If you examine any of the so-called “Turnings” within our last so-called “saeculum” you can find features of the other Turnings within; for example, the Cuban Missile Crisis can be seen very easily as a moment of, well, Crisis: it’s in the name after all. And that Crisis was about as existential as it got. And yet, we’re to believe that this was a High Era, to which Strauss and Howe would likely nod and say, “and we persevered,” as if that alone proves their thesis and doesn’t simply reveal hindsight or confirmation bias. Or let’s look at the 1990s leading up to 9/11: there are excellent examples throughout that decade that suggest an unraveling. And yet, the economy of the era is frequently seen as ideal, if only in the short term. The point is that none of these claims of “turnings” really hold any water outside of the imaginations of those who wish they had the ability to read the tea leaves. And yet, this is not to say that the effort to truly systematize history into something closer to science is trapped in the realm of tarot, astrology, and crystal healing. In fact, the modern starting point created by Strauss and Howe has, in some ways, led to one of the most interesting subdisciplines in history, and social science more broadly, I have ever seen.

…

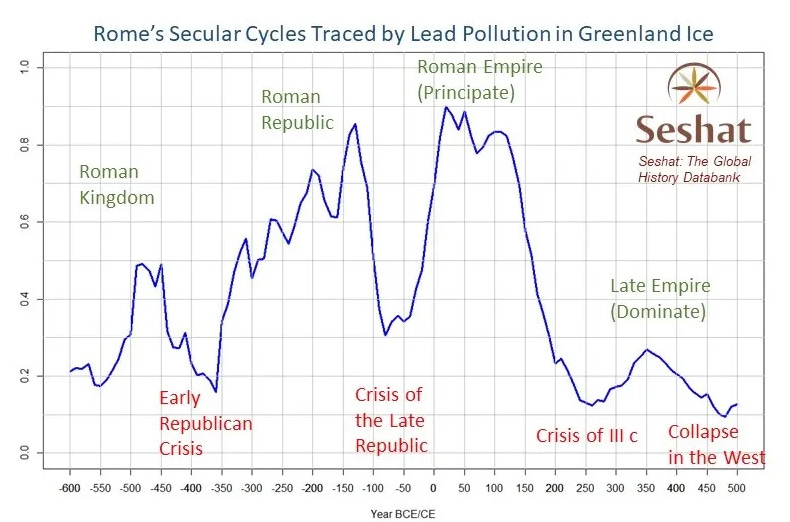

In their 2009 work Secular Cycles, complexity scientist Peter Turchin and historian Sergey A. Nefedov attempted to explain the patterns they were noticing when looking at various factors throughout human history, concluding in their introduction that:

“[I]t is becoming increasingly clear to specialists from very diverse fields—demographers and historical economists, social historians, and political scientists—that European societies were subjected to recurrent long-term oscillations during the second millennium CE.”

They go beyond simply looking at European societies, however (a major limitation one can point at when critiquing Strauss and Howe’s generational theories). Turchin and Nefedov continue and finish as follows:

“Furthermore, the concept of oscillations in economic, social, and political dynamics was not discovered by the Europeans. Plato, Aristotle, and Han Fei-Tzu connected overpopulation to land scarcity, insufficient food supply, poverty, starvation, and peasant rebellions. The Chinese, for example, have traditionally interpreted their history as a series of dynastic cycles. The fourteenth-century Arab sociologist Ibn Khaldun developed an original theory of political cycles explaining the history of the Maghreb. Are these phenomena, which at first glance seem very diverse, actually related?”

The in-text citations found throughout Secular Cycles (which I omitted from the quotes about for the sake of readability, even though I’m always a fan of APA-style citations) are extensive, and the evidence is very compelling, especially given that it’s multivariate, instead of simply vague observations about generational trends that sound good but really don’t have much behind them. But evidence for what? It’s not simply fluctuating grain prices—though that actually was the canary in the coal mine for this area of historical study for Turchin and Nefedov—nor is it related to “mere” class conflict. In writing Secular Cycles—which I really think probably deserves its own more dedicated analysis one day, because it deserves a much deeper look than I’m able to provide at the moment—Turchin and Nefedov went much further. They attempted to lay out “a synthetic theory that encompasses both demographic mechanisms (with the associated economic consequences) and power relations (surplus extraction mechanisms),” adding that “it does not make sense to speak of one or the other as ‘the primary factor.’ The two factors interact dynamically, each affecting and being affected by the other.”

To do this, they analyzed the historical data relating to things like demographic shifts (drawing from rich historical analyses as well, beginning with Thomas Malthus and moving forward). They also examine the phenomena related to social structure—namely, the divide between “commoners” and “elites” and how that has related to social mobility. They also look at levels of consumption at various periods and note how the same patterns seem to appear at the same periods of economic development for different societies across time and place. Turchin and Nefedov explain that when societies enter a “stagflation” stage in their economic development (that is, when inflation is high while the economy remains stagnant, i.e. not growing), things don’t tend to go well. As they write:

“During the stagflation phase […] economic inequality increases within each social stratum—peasants, minor and middle-rank nobility, and the magnates. Growing inequality creates pressure for social mobility, both upward and downward. Increased social mobility generates friction and destabilizes society. The growing gap between the poor and rich also creates a breeding ground for mass movements espousing radical ideologies of social justice and economic redistribution.”

Thanks to their use of economics as a general baseline (and that’s not a bad baseline to use when you’re proposing a grand theory of history), it’s hard not to see the pattern emerge, especially when applying them to whatever example you might choose. That becomes easier for the economically illiterate (of which I must count myself, minus the most tenuous grasp of the most basic macro- and microeconomic principles) when you look at what results of a stagflation stage, after elites engage in what Turchin and Nefedov call “surplus extraction” despite their declining wages—i.e. state breakdown, in which, “declining surplus production, popular immiseration, and intra-elite competition […] have a profound impact on the ability of the state to maintain internal order, or even to survive.”

Now we’re talking: the Crisis phase, as Strauss and Howe would put it, right? Because indeed, Turchin and Nefedov begin to make their proposal in earnest: that all of these secular cycles end in instability before making their way back to the first stage of the cycle. Where Secular Cycles differs from The Fourth Turning—apart from doing away with the woo-woo and trying to essentially systematize the process they’re describing—is that they refer to the cycles as being separated into two phases: A phase, and B phase, or “integrative and disintegrative trends.” During the integrative A phase, there is a “centralizing tendency, unified elites, and a strong state that maintains order and internal stability,” all while the population experiences persistent growth despite the presence of exogenous factors like natural disasters, disease, famine, and war. During the disintegrative B phase, there is “a decentralizing tendency, divided elites, a weak state, and internal instability and political disorder that periodically flare up in civil war,” all while population growth has slowed enough so that those same exogenous factors actually harm the “bottom line,” i.e. the stability of the population, often “[e]ven when the proximate Malthusian forces (epidemics, famines, and wars) are in abeyance.” Turchin and Nefedov further subdivide their secular cycle into subphases, bringing us back to the Strauss-Howe/Hindu time cycle norm of four stages—this time called the “expansion,” “stagflation,” “depression,” and “intercycle” stages—so it’s hard for the cynical jerk like me not to wrinkle his nose at what feels too good to be a coincidence, but again, it’s nonetheless important to point out again just how much more data-driven the Turchin-Nefedov method of cyclical trend analysis seems to be.

Data-driven is indeed a good way to describe it because their work set the stage for the subfield of history Peter Turchin essentially founded and has been catching on in various circles known as cliodynamics (“clio-” referencing the Greek muse for history, and “-dynamics” meaning the study of change). Credit where it’s due: Turchin is no guru, nor is he a figure who wishes to insert himself into the limelight the way most people purporting to have discovered the ability to read the future (which, too, is not something he’s claimed he can do). Turchin “merely” wants to revolutionize the field of history and open it up to a more scientific approach. And when it comes down to that, I think the project of cliodynamics is one of the most exciting things to be introduced to any social science in a very long time (if I were to make a comparison, I guess it would be to the rapid advances in bio- and neuropsychology in the last several decades). Turchin has the ambition, but he doesn’t have the hubris in other words, and I do really hope to give his work—all of his work—the proper analysis and coverage it deserves one day instead of the quick-and-dirty-job I just gave here. But I also bring this up—namely Turchin’s lack of hubris—to contrast that with the reality that lies behind such a revolutionary hypothesis: that plenty of people with undue hubris will always attempt to use such ideas for their own selfish or ideologically-possessed ends.

As Carnegie Mellon student and host of the Increments podcast Ben Chugg recently wrote:

“[T]rends are not universal laws — trends break. Looking for the laws of history is begging the question. By almost all metrics, after all, the modern world looks entirely different than previous eras. Moreover, exercises in predictive history don’t have a great track record. The desire to uncover the laws dictating human destiny is nothing new. Religious apocalypticism alleges that history will end with the return of a deity or a heavenly kingdom come to earth. Thomas Malthus believed that history was characterized by inescapable cycles of abundance and scarcity. Hindu cosmology contends that history is cyclical. Adolf Hitler believed that history led to an inevitable race war. Karl Marx that it led to a class war and ultimately, to a communist utopia.”

Chugg seems to cast a more critical eye on Turchin than I do—and more power to him—but in an interview given on the ABC’s Future Tense podcast, he also agrees that something as fundamental in nature as cliodynamics desperately requires continued study. And while I am indeed excited to see where cliodynamics goes as a field—whether it fails or succeeds—I can always appreciate kill-joy skepticism. And Chugg’s above quote contains quite a few historical reminders that I think bear remembering for why, as exciting as cliodynamics is, and as fun as Strauss and Howe’s generational theories can be, looking for historical cycles as a guide to the future is no less utopian, irrational, and soaked in blood than assuming we all live on a progressive arc toward a just promised land. Citing Karl Popper’s 1957 work The Poverty of Historicism, Chugg points out probably the most important thing the philosopher observed regarding the idea of “inexorable historical destiny”; that “it is logically impossible to know the future course of history when that course depends in part on the future growth of scientific knowledge.” In other words, future ideas—which are informed by far more than simply previous ideas; that’s pure social constructionism—are impossible to know today, no matter what we might claim. This is one of the main underlying reasons that I make the deliberately provocative claim that there are no such thing as Nazis today.

Yet I would be lying if I said there wasn’t something compelling about the idea of cliodynamics in particular (and historical cycles in general), especially as someone who studies history as much as I do. Many of you might remember that when I was discussing Savitri Devi in “The Hitler Avatar and His Masochistic Priestess” episode of History Impossible, I quoted from Ben Teitelbaum’s masterpiece, War for Eternity, where he laid out the appeal that this likely has for some people, writing that “cyclicality ascribes an unusual importance to history, for here, our past is nothing to overcome or escape, it is as well our future,” adding that “perhaps some of the unease we might feel in the face of [striving toward a better future] is that of the unknown.” I do indeed think these things are true. But more to the point, there’s a particular appeal in cycles, I think, for people who love to study and talk about history—this is because we’re more aware than most people of how complex history actually is, so perhaps paradoxically it compels us to look for concrete explanations for why there seems to be so many patterns in the events we look at.

And yet, I will likely always have an underlying problem with a belief in cyclical time or history. As we’ve covered many times, I have a problem with notions of inevitability. With hindsight, just as with ideological possession, anything can be inevitable. And as we’ll be getting into in a moment, time does not determine patterns; people do. This is partly why believing in historical cycles is no substitute for a progressive view of history, despite it providing some of the best refutations for such a delusion. But what many people attracted to the idea of historical cycles are really not seeing—at least in my view—is just how similar both views of time actually are when you place them under the historical microscope.

…

In a collection of one of his character’s aphorisms, the famous science fiction author Robert A. Heinlein once wrote that “A fake fortune teller can be tolerated. But an authentic soothsayer should be shot on sight. Cassandra did not get half the kicking around she deserved.” Referencing the Greek myth of the Trojan priestess Cassandra—who was cursed by Apollo to tell true prophecies that would never be believed by man—Heinlein was also suggesting something pretty profound: that anyone who predicts the future is basically harmless since they’re pretending that they can do something that’s impossible (while also suggesting that if someone actually had that ability, they would be profoundly dangerous). While we’ve certainly seen that danger depicted in films and books—Minority Report’s Pre-Crime Division comes to mind—the ability to read the future has always been something humans have strove to achieve, as mentioned earlier. There’s a reason the 450-year-old predictions of Nostradamus still carry cultural purchase. This desire is not just at the core of believing in historical cycles, but at the core of all Utopian assumptions, including my now-dead horse that is the progressive view of history.

When it comes down to it, the cyclical view of history is just as utopian as the progressive view of history because they both rest on the fundamental premise that the future can be known. In fact, the notion of historical inevitability is what has animated all the totalitarian regimes of the 20th century, and that supposed inevitability was always informed by two very important assumptions:

That history, or time, operated in cycles.

That these cycles could be harnessed in order to progress one’s nation (or species) into a glorious future.

As is probably clearest, at least to listeners of History Impossible, the Nazis—and somewhat by extension, their ideological ancestors in 19th century American eugenics circles—did indeed believe in both cycles and progress. Everything in the early Nazi ideologues’ heads was related—directly and indirectly—to a return to a past glory; an overdue ascension. This could be driven by “scientific”—and by extension, racial—progress, as the Nazis conceived of it. The progress that they were pursuing was simply the engine that drove the cycle in which they inhabited toward their deserved place at the top of the global hierarchy, defined purely by the glory of their supposed race. This is well-trod territory at this point, but it does bear repeating in order to understand what I, at least until recently, believed made the Nazi ideology unique (and it is still quite unique, in many ways). However, it’s pretty clear to me that this dual belief in progress and cycles informing one another wasn’t unique to the Nazis. In fact, the more one looks, the more you could see how both views on time and history informs all totalitarian regimes in general.

You’d be forgiven for thinking the Soviets and other communist regimes were solely falling prey to progressive theory of history—and they were, don’t mistake me—but they were, like the Nazis, also animated by notions of cycles through history. Theirs wasn’t a New Age-esque, esoteric belief in ancient races, however; with certain personality cult-driven exceptions, 20th century communists’ beliefs were rooted in a belief in rational, objective “laws of history” under the heading of “scientific socialism” (which honestly sounds a bit too similar to “scientific racism” to me, but that’s just my bias). While this type of socialism is usually contrasted with utopian socialism—the kind practiced mostly by 19th century Western intellectuals primarily in France, Great Britain, and the United States that didn’t necessitate class struggle—it was no less utopian in its ultimate vision. It was derived from Marx’ and Engels’ views on economic class struggles throughout history, which Lenin and his ilk saw as those aforementioned “laws” that governed history (and it should be noted that while Marx had a more squishy view of human progress than Lenin would many years later, he nonetheless believed in it). This way of looking at the world—that of cycles of class conflict—was what prompted revolution and the so-called dictatorship of the proletariat that Lenin sought to implement in early 20th century Russia. Through this dictatorship and its Five Year Plans and the like, Russia would industrialize and become a power to be reckoned with, and the center from which this scientific socialism would spread. Very similar types of promises of progress were made throughout the communist world, particularly in the People’s Republic of China leading to disastrous results, but by no means exclusively. Progress would take hold and it would come about by any means necessary.

To put it as bluntly as I can: if you truly see history as something operating in cycles and thus making your worldview or struggle “inevitable,” there is nothing you won’t accept—no matter how monstrous—if that confirms your predisposition. And if you truly see history as having a moral arc toward progress—justice, if you will—there is nothing you won’t accept that guarantees (or at least that you believe guarantees) such a future, and nothing you won’t accept that destroys anyone or anything that you think stands in that progress’ way. That these ways of looking at the world continue to gain purchase in American society the further we move into the 21st century is not something I take lightly.

Beliefs in cycles and beliefs in progress are not the conduits to free, democratic societies. They are the very things that destroy them.

…

So where does that leave us with the question of human progress versus time cycles, of the progressive view of history versus the cyclical one? If not those, then what? How can I question or deny that progress has undeniably been achieved? How can I question or deny that there are trends throughout history, even if they aren’t 1:1 the same? Well, not only can I explain why it’s pretty understandable to make either of these assumptions, but if I may be so bold, I think I can explain, at least in part, how history, broadly speaking, works.

The fact of the matter is, we do feel progress and we do feel cycles, or at least the appearance of them; by “feel,” I mean “perceive” in these cases. The thing is, as important as perception is to literally everything, perception does not equal reality. I don’t mean to say we can capture objective truth—or objective history for that matter—because I’m not sure we can. But I do believe we should reject subjective truth being presented as The Truth, which unfortunately is where these two conflicting-yet-complimentary worldviews are at their most faulty. We may not be able to actually capture objective truth, but we can be aware of psychological biases within ourselves that make us believe we can.

I submit that progress, as we often intuit it, is felt because technology progresses very rapidly while we, as a psychosocial species, stay largely the same (or, if we’re being charitable, are changing VERY slowly). For example, medical advances lead to longer, less fraught and lonely lives, allowing us to grow old with our loved ones. Or advances in communication, which allow us to stay in contact with people we might otherwise have lost touch with, or meet new friends. Or advances in food production, guaranteeing that not just the developed world doesn’t starve to death, but vast swaths of the developing world. These things have never happened before; these advances have indeed improved our lives. And yet…can we really say that we have changed all that much as a species? Have we truly “progressed,” especially at our base, psychological level? It’s true that environmental pressures help shape our individual and social psychologies (while interacting with genetic predispositions and other non-social influences), but it’s also pretty difficult to deny that, while history doesn’t repeat, human behavior clearly does. How else can we even attempt at explaining why, say, social media “witch hunts” so very closely resemble—in tenor and motive, if not in physical consequence, of course—the actual witch hunts of nearly 400 years ago? How else, if we stick to the History Impossible mythos, can we explain the same sorts of behavioral reactions to a global pandemic—in-groups banding together, out-group demonization, hyped up radicalism, and more—occurring during both the 1918 influenza pandemic and the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020-2022? How else can we explain the massive populist backlash occurring in both 1876 and 2016 due to the same sociopolitical and social psychological factors—rising immigration, widespread perceptions of corruption, outrage at growing inequality, a big financial crisis, and the emergence of demagogues—occurring in the same span of time? The truth is, we are complex, adaptable creatures that do everything we can to maintain our inner status quo, regardless of what is happening all around us, however marvelous or profound.

And while it may be tempting to chalk all these similarities up to, well, cycles, that would be missing the point. Notions of cycles are just as much tied up in our biased perceptions as notions of progress. Cycles are felt because we are pattern-recognizing creatures who see familiarity around every bush; if we didn’t, we would not have lasted long as a species. Identifying patterns have allowed humans to recognize magnitudes of difference, identify various cues, and most importantly, act on that identification. As Aditya Shukla has put it, “our senses adapted alongside our cognitive ability to make sense of sensory signals”; this hasn’t changed all that much, even over millions of years of evolution. It’s vital for our continued survival. And since our psychologies are essentially designed to protect us and motivate us to pass on our genes, the range of behaviors—which is what drives historical events—is relatively limited and thus constrained; hence the feeling of patterns of events, rather than patterns of stimuli. In a way, the fact that so many people can recognize patterns and abstractly interpret them in such a way that they see recurring events throughout history so clearly is quite remarkable; it’s a testament to our species’ cognitive evolution.

History does not repeat. It does not rhyme either. It does not progress, especially not in a moral sense. It is an abstract interpretation of time; it is, in essence, a story. It’s not untrue, by any means, but nor is it objective and it certainly can’t be used to predict the future or even, if I may dare to say, inform the present. But it can be used to inform us about us—about who we are as people. About how we reacted to various events in the past in potentially overlapping ways with how we react to events in the present, informing us how we’re really not all that unlike our ancestors. It doesn’t preclude change, let alone change that can be widely seen as an improvement for both broader society and those whom society forgot. It doesn’t preclude the possibility that our ancestors perhaps had some things right in how they reacted to the world around them, and in our arrogance as moderns we have completely written them off as problematic at best or genocidal at worst. History is, as it always has been, a way to learn about ourselves, in the moment, here and now. And yet: so many of us seem to have forgotten what that truly means, choosing instead to learn about things that make us feel good about ourselves or comforted in certainty as we enter an uncertain future.