The Happy and the Godless

A brief digression into religious anthropology

It is sometimes claimed by some that the religious impulse is natural and inevitable in human beings and even that true happiness can only be found with the meaning brought to us by religious faith. But is that actually the case? Is it possible that there is a society, however small, that has found the secret of happiness without the need for religious faith?

Having just released the most recent episode of History Impossible that I, at least would like to think, threw us gracefully into the weeds of American religious history and America’s potentially eternal religious character, I thought it might be prudent to take a more anthropological and even linguistic look at the nature of religion itself by using the case study presented to us by the Amazonian Pirahã people. I feel that they serve as a fundamental counterpoint to the reality of United States culture when it comes to the question of religious belief.

This is not to say that they—a relatively isolated tribe with very little in the way of modern-day accoutrement that we would recognize—are comparable in most ways; what it is to say is that they serve as the antithesis of American culture when it comes to the religious question. In other words, despite my seemingly deterministic view on American culture being fundamentally shaped by Protestant Christian forces whether we like it or not, I do not think this is the case with all cultures. Nor do I believe, as it will become clear with this essay, that all people need religion to be happy. And even though it is hard for me to imagine this, the religious impulse does not seem to be an inevitable feature of all human nature. I think the exception provided by the Pirahã act as good, at least anecdotal evidence to the contrary. In my opinion, thanks to the work of linguist Dr. Daniel Everett that this is indeed possible, which is, in turn, thanks to his decades of work with the Pirahã. But there is a lot to cover, so let’s get started with explaining what an “atheist society” conjures in the modern, mostly Western imagination.

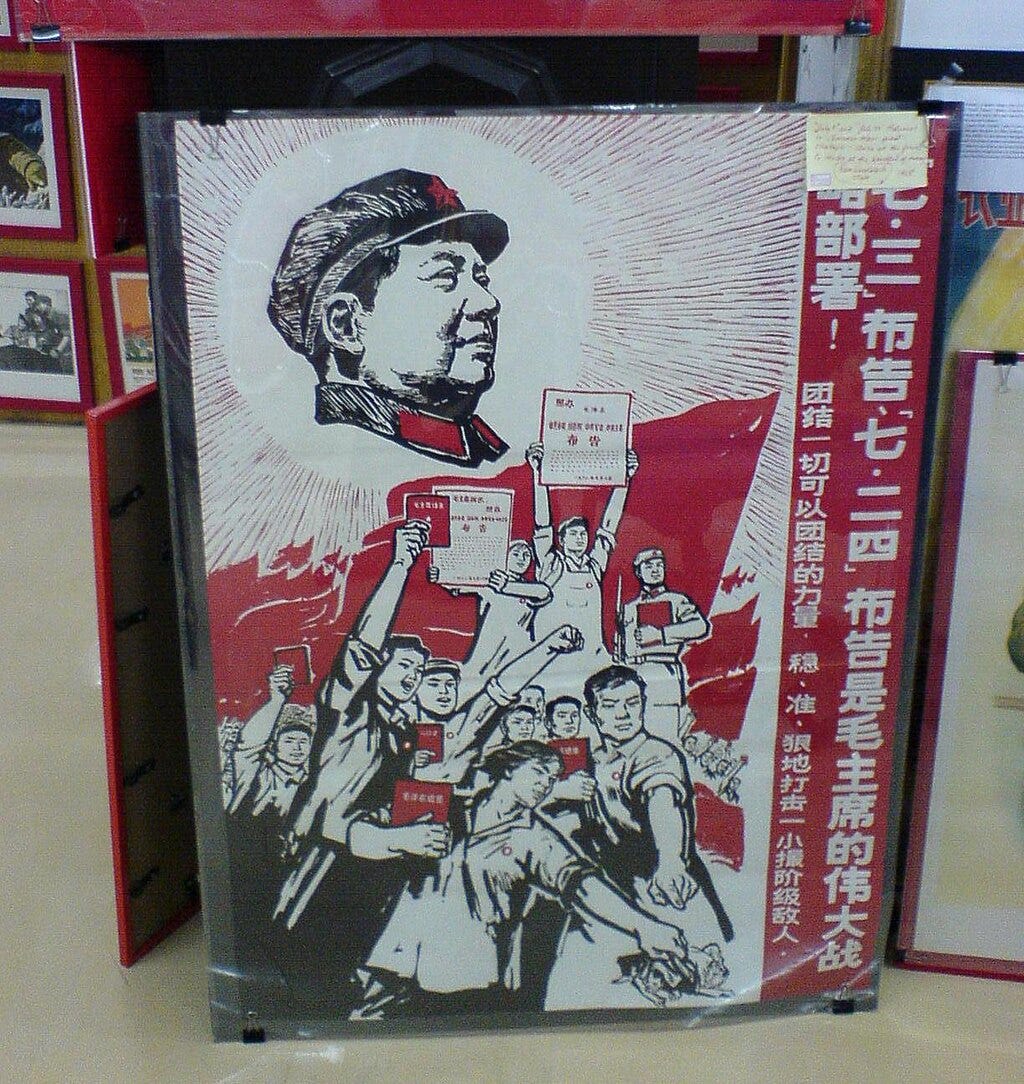

It is very unlikely that when one hears of an “atheist society” that their mind doesn't immediately dart toward the ostensibly secular dictatorships of the likes of Mao Zedong or Joseph Stalin. Characterizing Stalin’ and Mao’s regimes as atheistic is thanks to plenty of things that both of these men said, and efforts made to crush traditional, often religious parts of their societies, including the demolition of places of worship and the smashing of idols. However, what is missing from this analysis of Russian and Chinese state communism is the fact that they were attempting to wipe the slate clean of religious influences not because they found the religions or traditional beliefs questionable in and of themselves—primarily Christianity and Confucianism, respectively—but rather because they wanted to create what was in essence a new, civic religion—that of communism. One therefore needs not look far to see how it is a bit of a misnomer to label these societies or their totalitarian dictators as “atheist.” As the late polemecist Christopher Hitchens put it in his famous (or infamous in some circles) book God is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything:

For most of human history, the idea of the total or absolute state was intimately bound up with religion. A baron or a king might compel you to pay taxes or serve in his army, and he would usually arrange to have priests on hand to remind you that this was your duty, but the truly frightening despotisms were those which also wanted the contents of your heart and your head. [...] It is almost unvaryingly that we find these dictators were also gods, or the heads of churches. More than mere obedience was owed them: any criticism of them of them was profane by definition, and millions of people lived and died in pure fear of a ruler who could select you for sacrifice, or condemn you to eternal punishment, on a whim. The slightest infringement—of a holy day, or a holy object, or an ordinance about sex or food or caste—could bring calamity. […] This was even true when the divine right of despots began to give way to versions of modernity. The idea of a utopian state on earth, perhaps modeled on some heavenly ideal, is very hard to efface and has led people to commit terrible crimes in the name of the ideal.

In other words, it is better to see the two most infamous incarnations of communism as less inspired by an atheistic creed than it is to see them as inspired by a materialistic one, in which worship is directed at the state—and often the dear leader—rather than the spiritual realm.

After the 1949 revolution, it came to be said that “Mao is the star of salvation for the Chinese people.” In similar religious language, Stalin’s regime was described as “the Land of the Soviets is a light to the nations, a living beacon illuminating the road to the ‘promised land’ called the socialist world, a ‘torch lighting the path to liberation from the yoke of the oppressors’ for all the peoples of the world!” And lest we forget, even though he has been dead for over three decades, Kim Il-Sung (along with his own son Kim Jong-Il) is considered the “eternal leader” of North Korea, probably the last twentieth century communist dictatorship. The original constitution reads as follows:

Under the leadership of the Workers' Party of Korea, the Democratic People's Republic of Korea and the Korean people will uphold the Great Leader Comrade Kim Il Sung as the eternal President of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea and Comrade Kim Jong Il as the eternal Chairman of the National Defence Commission of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea. [Emphasis added]

What else can one call such a state of affairs involving leadership from beyond the grave (apart from Hitchens’ own clever neologism “necrocracy”) but that of a religious cult?

Keeping these observations in mind, it is also important to note that it also would not do to label Adolf Hitler and the Nazis, as public figures like Jordan Peterson and Dinesh D'Souza have done, as possessing an “atheistic doctrine” or being “atheistic” in general. While it's again certainly true that there was a very pointed internal rejection of Christianity within the Nazi higher-ups, when examining the true beliefs held by many of these figures—Hitler, Himmler, and Goebbels included—there remains an inescapable notion that this belief system they called National Socialism was, at its core, fundamentally religious in nature.

As observed by historians like Eric Kurlander and discussed right here on History Impossible many years ago, the Nazis possessed something known as a “supernatural imaginary” as part of their very ideological foundation. Nazi Party doctrine originated from several places, but the sort of moment of conception came from the esoteric writings of the philosopher and occultist Helena Blavatsky, who created what became known as theosophy in 1875. This field of “study” was mostly concerned with what we probably lump in with “ancient aliens” talk today but in truth it was just a new coat of paint on the musings of folks desperate to believe in the Atlantis myth: a secret “lost science” or “lost faith” that had died long ago and that a godhead was needed to keep the world in order.

It did not take long for this type of philosophy to morph into more nefarious incarnations, including the proto-Nazi racial-spiritual esoteric pseudo-science known as “ariosophy”, the adherents of which indeed believed that there was once a race of supermen—the Aryans—who had essentially died out thanks to miscegenation with lesser “mongrel” races like the Africans and the Jews. While it would hardly do to claim that Nazi Germany was a Christian regime—especially considering the aforementioned hostility with which Christianity was regarded by Third Reich leadership—it is therefore hardly a stretch to see that 1.) the Nazi Party would have become nothing without its spiritual godhead Adolf Hitler, and 2.) that this resulted in a very religious kind of structure within Nazi society.

…

So as unlikely as it is for one's mind to typically find itself drawn to the images of these megalomaniacal men who unfortunately came to define much of, if not all of the twentieth century, it may be less likelier still to many of you reading that the term “atheist society” would conjure the image of a small tribe of hunter-gatherers living in the Amazon Rainforest. This is where an introduction of the relatively unknown Pirahã people, or the Hiatíihi, as they call themselves in their own language, can be illustrative.

Just as it is unlikely that we would make the connection between a nomadic Amazonian tribe and the notion of a godless culture, it's just as unlikely that the developed nations of the world would have any awareness of their existence in the first place if not for former Evangelical Christian missionary and linguistic anthropologist Dr. Daniel Everett, who spent many years studying and even at times living with the Pirahã people, his time with them stretching from the late 1970s until the early 21st century. In a profile written about him by the New Yorker in 2007, Dr. Everett described the Pirahã people and his admiration of them:

The Pirahã are supremely gifted in all the ways necessary to ensure their continued survival in the jungle: they know the usefulness and location of all important plants in their area; they understand the behavior of local animals and how to catch and avoid them; and they can walk into the jungle naked, with no tools or weapons, and walk out three days later with baskets of fruit, nuts, and small game.

Dr. Everett first encountered the Pirahã in 1977 when he was 25 years old and on a mission, as he saw it, from the lord. As he himself puts it, it was “an undergraduate diploma in 'Bible and Foreign Missions' from the Moody Bible Institute of Chicago.” His mission was quite simple: spread the good news with this relatively isolated tribe, bringing them into the Christian fold. The difficulty—and what would ultimately come to define his journey with these people—was coming to understand their language so they could communicate effectively together.

The groundwork, as he observed in 2009, had already started to be laid with the Protestant missionaries from his own organization with whom the Pirahã had interacted in the late 1950s into the 1970s. In truth, however, there had been previous contact with this tribe as far back as 1784 when Catholic missionaries encountered the Pirahã. Where their attempts to convert the people to the faith had failed, Dr. Everett and his Protestant organization were determined to succeed. As Dr. Everett, becoming increasingly trained in both linguistics and with his experiences with the tribe, would come to understand, the more he came to understand the Pirahã's language and thus their culture, the more he realized the potential futility of his efforts to bring them into the arms of Christ.

The language of the Pirahã is at the core of what has both fascinated and perplexed many researchers—namely linguists—the more they've come to understand about them, largely thanks to the decades of research completed by Dr. Daniel Everett. As he discovered, the Pirahã’s manner of discussing existence itself seems to be merely restricted to what falls inside personal experience. The notion of history is largely foreign to them. This is not to say there is not a sense of history when it comes to the immediate lived experience of elders being passed to their children and children’s children, but grand narratives of triumphant battles or noble defenses or destined conquests are largely alien concepts to the Pirahã. Strange as it may sound, this likely relates to tribe members’ unwillingness to learn how to preserve the meat they receive through hunting and trading, since they tend to eat what they obtain almost immediately. In other words, they work with what is in front of them in the here and now; they are, to use the wellness industry’s parlance of our times, living completely in the present.

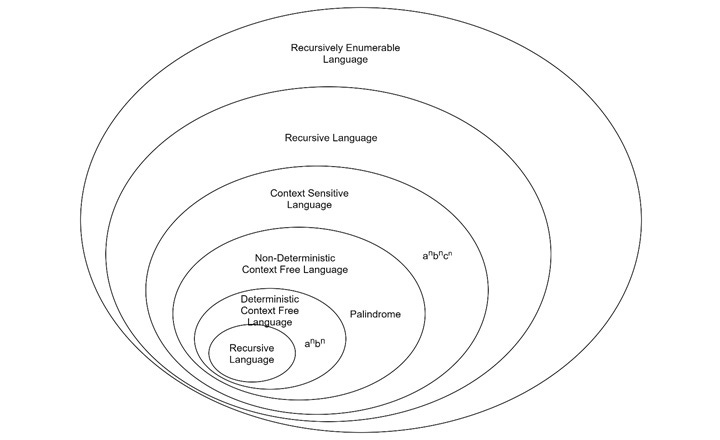

They also lack what would be seen as a traditional sleep schedule, taking periodic naps ranging from 15 minutes up to two hours. It would also be a misnomer to call the Pirahã “uncontacted” since they frequently trade with outsider traders, usually with Brazil nuts and even sex, in order to receive valuable resources like gunpowder, sugar, and alcohol. What makes all of this so interesting is that while it is clear that the Pirahã live in such a way that they are almost always living in the present, it also reveals why the most perplexing aspect of their language is what has presented the biggest challenge for a lot of linguists: their lack of a number system. Linguists like Noam Chomsky (who, being the classy guy he has always been, called Dr. Everett a “fraud” for daring to challenge Chomsky’s received wisdom) have claimed that the most basic unit of a language is that of recursion, or essentially numbering things, but the research conducted by Dr. Everett with the Pirahã has essentially revealed this to be wrong, or at least not as ironclad as figures like Chomsky believe.

Dr. Everett contends that it is not that the Pirahã are incapable of learning numbers either, as some have suggested, but that they simply choose not to. And when one considers how, to use this word again, present the Pirahã people tend to be in the extreme, this actually makes more sense than one might initially assume. When one engages in trade, how does one, for example, quantify sex? There is a reason this is used as trade, especially when considering that the Pirahã don't tend to store the things they obtain, with the exception of tools they use to hunt. They only obtain what they need in the immediate term, never asking for more. What reinforces this sense of a society being completely present (and happy) is the story recounted by Dr. Everett about what typically happens during an Amazonian rainstorm:

In a big rainstorm in the Amazon, a pretty common occurrence, the flimsy little Pirahã houses very often blow over at night, at three in the morning. And everybody’s sopping wet. What do you hear when this happens? Everybody’s laughing. They think it’s the funniest thing that ever happened. My house blew over! What do they do? They move into somebody else’s house.

This sense of immediacy is what leads to the most crucial aspect of Pirahã society: the complete lack of hierarchy and coercion. A member of the tribe will never try and tell any other member what to do, and anyone who might attempt to do so will be treated as someone not to be trusted. What's more, if someone attempts to make any sort of claim in which the subject of the claim falls outside of the realm of personal experience, the claim is dismissed out of hand. This lack of hierarchy and unwillingness to trust anything said that comes from outside the realm of personal experience is actually what leads to the most-talked-about aspect of the Pirahã in more mainstream, non-linguist sources: their complete lack of a deity or even the concept of a supreme being. In other words, to the Pirahã, there is no god.

While there are claims of individual spirits within the Pirahã experience, they always and only inhabit concrete real-world objects. One can claim that this doesn't make them godless, but they remain steadfast in their unwillingness to accept that the world was created by some supreme being. In fact, as Daniel Everett, fulfilling his role as a missionary, tried to explain to them the power and good news of Christ, the Pirahã simply lost interest. As Dr. Everett recalled in a talk he gave on the subject in 2009:

[T]he first thing I had to deal with when I got to the Pirahã was that I hadn’t done my background reading, as any anthropologist would have done. As a missionary, I felt that this was a new story with me and God. Why did I need to read about these people? They were and are monolingual, one of the only groups known in the world that are completely monolingual. So I got off a little Cessna missionary plane and tried to talk to them and they said something like, “Xaói xáo hi ahoáisahaxai. Xapaitíiso abaxáígio hi ahoaáti.” It means “Don’t speak to me with a crooked head, speak to me with a straight head.”

In other words, when one speaks to an individual in the Pirahã tribe, one better give it to them straight. This resulted in difficulty for Dr. Everett, of course, being a missionary with a truth to spread. But ultimately, it became impossible for him to get through to the Pirahã in any of the villages he visited. In the same talk from 2009, Dr. Everett recalled what one of the Pirahã men said to him in a conversation they had after solid communication had been formed between the men:

[Y]ou know, we’ve had people tell us about Jesus before. Somebody else told us about Jesus, and then the other guy came and told us about Jesus, and now you’re telling us about Jesus, and we really like you but, see, we’re not Americans and we don’t want to know about Jesus. We like to drink, and we like to have a good time, and we like, you know . . . [the equivalent of multiple sex partners is the way it came out, and that applies to both genders].... So we really don’t want to hear about that. You can stay here. We like you, we like your kids, but we don’t want to hear about Jesus or God or anything any more, we’re tired of that.

Ultimately, as time went on, the words of this man—and the philosophy of the Pirahã—had an incredible impact on Dr. Daniel Everett. It would ultimately up-end his life and result in, of all things, the loss of his faith in god and Christ. He had, in fact, already begun experiencing doubts in his beliefs as far back as 1982, and finally was able to admit to himself that he had lost his faith by 1985, but not admitting to anyone else until 1999. This would cause a rift between himself and his very Christian family (though by 2008, they had reconciled), but it is important to note that despite the consequences felt by Dr. Everett for his loss of faith, he ultimately did not see this as a failure, but rather an expansion of his worldview. This allowed him to continue his time studying the Pirahã and learning to appreciate what kind of lessons they may be able to impart upon the Western world, namely the psychological ones. As Dr. Everett concluded in his 2009 talk:

We learn that not all the things we thought were universal are universal, not all the things that make people happy are necessary to make people happy, and that the idea that somebody died on a cross 2,000 years ago that nobody ever saw, nobody knows anybody who ever saw, has any relevance to my happiness or my life in any way today. We might take a lesson from the Pirahã’s skepticism there.

This is an admirable, and interesting sentiment from Dr. Everett; skepticism is one of the greatest strengths and skills human beings have developed and can deploy. It certainly has its trade-offs—a necessary feature of conspiratorial thinking and paranoia—but it has allowed us to get closer to that always-slippery thing known as “truth.” However, Dr. Everett’s observation about the split between the Pirahã and our modern sensibilities is perhaps not quite as he realizes. Certainly, their skepticism of Western universal truth claims about the Almighty differs from most Westerners’ views, especially considering their unique language structure and how that has informed their development over the centuries. However, is skepticism not baked into the fundamental structure of Protestant Christianity? Was skepticism—admittedly more directed at earthly institutions rather than the existence of god itself—not a fundamental pillar of Martin Luther’s own revolution against the Catholic authorities of the sixteenth century? Was skepticism not the central motivating force behind America’s Great Awakenings?

Skepticism, it seems to me, is a feature of the human experience, not a bug, and not something that religion precludes people from experiencing and expressing. In fact, religious belief strikes me as a reinforcement of that human feature. Skepticism can either result in a revolution of that religion, or it can produce a backlash that demands a return to tradition; either way, skepticism is at play. What makes the Pirahã distinct is that their skepticism has manifested differently thanks to their unique development as a people, and their relationship with language. It has seemingly inoculated them against Western social traditions, but it also reveals—as best I can tell—that skepticism is indeed a feature of the human experience and manifests in myriad ways. It also has not precluded them from happiness, as Dr. Everett observes. I have been on the record saying that I do not believe human nature changes much across time, thus giving us the illusion of history repeating itself. However, when looking at the story of the Pirahã, I do take Dr. Everett’s point that not everything is universal, including what provides meaning and happiness to us as human beings.

…

References:

1. Hitchens, Christopher, “God is not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything”, 2007

2. Orwell, George, “The Prevention of Literature”, Polemic Magazine, 1946

3. Kurlander, Eric, “Hitler's Monsters: A Supernatural History of the Third Reich”, 2017

4. Colapinto, J., “The Interpreter”, The New Yorker, 2007, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2007/04/16/the-interpreter-2

5. Everett, D.L., “The Pirahã: People Who Define Happiness Without God: Daniel Everett”, Freethought Today, Vol. 27, No. 3, 2010, https://ffrf.org/publications/freethought-today/item/13492-the-pirahae-people-who-define-happiness-without-god

6. Everett, D.L., “Don't Sleep, There Are Snakes: Life and Language in the Amazonian Jungle”, 2009

7, L3. Everett, D.L., “Recursion and Human Thought: Why the Pirahã Don't Have Numbers”, Edge, 2007, https://www.edge.org/conversation/daniel_l_everett-recursion-and-human-thought

8. Barkham, P., “The power of speech”, The Guardian, 2008, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2008/nov/10/daniel-everett-amazon

9. Else, L. and Middleton, L., “Interview: Out on a limb over language”, New Scientist, 2008, https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg19726391-900-interview-out-on-a-limb-over-language/

This is a really great article, I need to listen again but I especially appreciated the point about our most well known examples of atheism mostly being the leaders replacing God with themselves.