The Legacy of Empire

A Brief Review of Policing America's Empire: The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State by Alfred W. McCoy

Seeing as we just finished our sequence of episodes and conversations regarding the contentious concept of empire and imperialism, I figured it would be good to close us out before moving onto the final set of grad school-related episodes with a short review I wrote of one of the books we used in my class that discussed American empire. It’s ironic how short this review is—not just because I tend to be, ah, a bit long-winded myself—because the book in question, Alfred McCoy’s Policing America’s Empire, is a bit of a doorstopper. Ultimately, McCoy provided what could be reasonably described as a definitive account of the United States’ involvement in the Philippines for over a century, and I think the length and breadth and depth of his work shows it, and really contributes to the overall scholarship.

The review didn’t really get too far into the details, nor did it really get into the critiques I had of the book, and there were a few. Primarily, it had to do with McCoy’s motivated reasoning that was made obvious within the first chapter—that this was indeed an in-depth history, but it was also a response to the then-new War on Terror of the early 2000s. This raises the issue of the intersection of contemporary politics and history and the deeper question of weaponizing history to serve a contemporary political project, and while I think McCoy deserves credit for not attempting to hide his beliefs in the continuity of American imperialism, he still blurs this line. This can be off-putting for some, and not just when they agree with the conclusions at which McCoy arrives (and for the record, I mostly did when I read this work).

Ultimately, I don’t see too much of an issue of current events informing our historical interests, but I do believe that if our contemporary beliefs conflict with the realities of history, that becomes a problem. This is why I try my best (but by no means always or even often succeed) to let my understanding of historical events guide my views toward modern issues. Sometimes I just try to keep those things separate to save myself the trouble. McCoy didn’t take that route with his book and even though the connections between current events and historical events might feel strained, he makes a good, honest, open case for those connections.

Anyway, please enjoy this short review of Policing America’s Empire: The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State.

…

September 11th, 2001 will likely loom large in the American imagination for the entirety of its history. Apart from the shocking and violent loss of life, it produced many downstream effects felt around the world, not least of which including the invasions and largely botched attempts at state-building in Afghanistan and Iraq. However, it also led to the rise of something many Americans likely take for granted in the 2020s, i.e. the rise of the surveillance state, starting with the passage of the USA PATRIOT Act of 2001. This, and subsequent revelations by whistleblowers like Edward Snowden, has led to a greater awareness of how exposed Americans' personal information is to agencies within the federal government and a persistent (if ultimately muted) fear of how that information might be used.

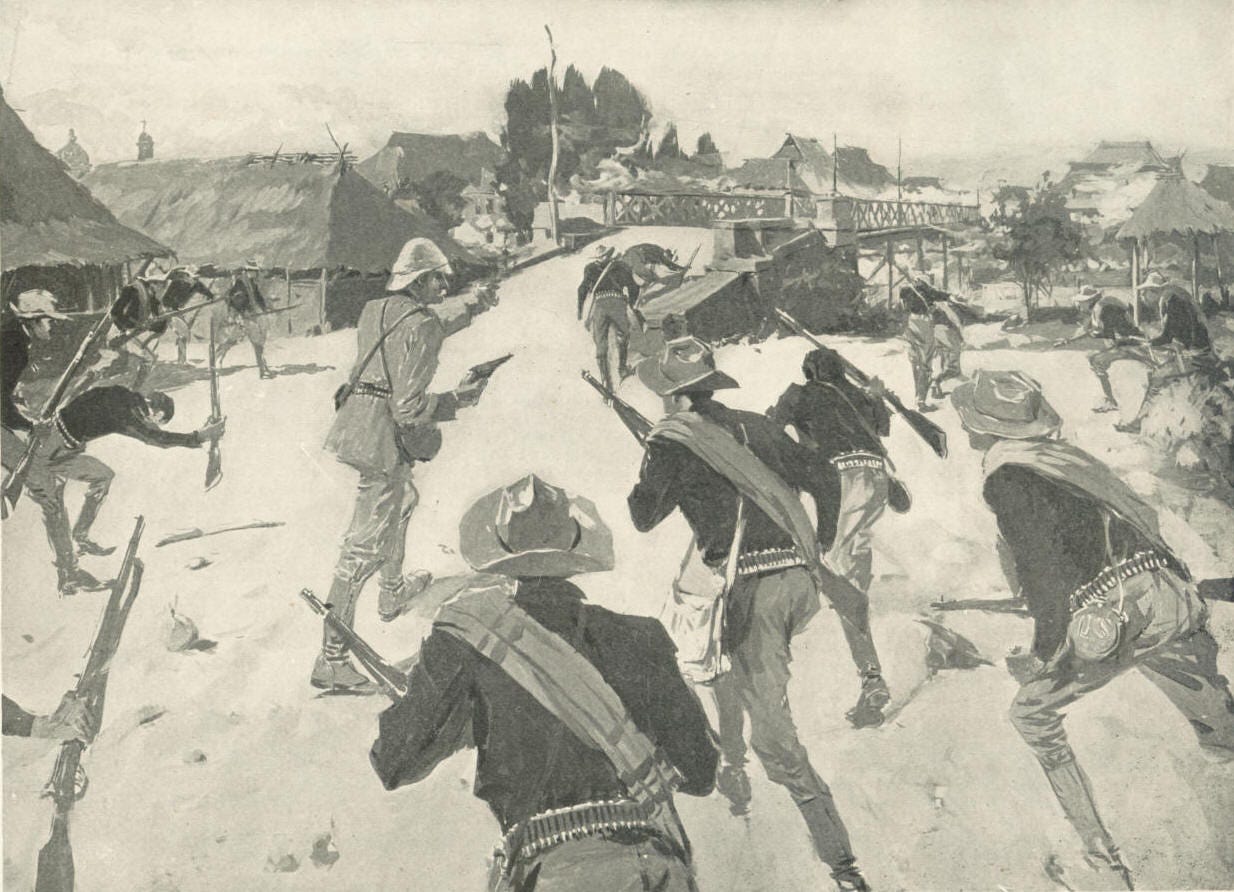

However, not many Americans, even the most informed civil libertarians, would expect that the rise of the modern surveillance state and curtailing of civil liberties in the wake of the 9/11 attacks had its roots in a foreign conflict over a century old. And yet, that is exactly the case being made by Alfred W. McCoy in his 2009 tome, Policing America's Empire: The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State. In this work McCoy takes the reader through the 100-year history of the United States' imperial involvement in the Philippines, starting with the 1898 invasion as part of the Spanish-American War and culminating with the renewed alliance and presence of American troops at during the birthing pangs of the War on Terror. As McCoy writes, “colonial pacification, with its diverse arenas of conflict, proved an ideal laboratory for innovation in the realm of intelligence and counterintelligence,” hallmarks of the modern surveillance state.1

McCoy's main contribution to the preexisting scholarship in both Philippine and American imperial history by demonstrating the continuity and downstream effects of the United States' pacification efforts in the Philippines after the conclusion of the Spanish-American War and after the outbreak (and conclusion) of the Philippine-American War from 1899-1902. As he explains, previous scholarship on the U.S. involvement in the Philippines “focused on the initial, conventional phase of U.S. Army combat operations,” which McCoy points out as being “of secondary importance in the resolution of what was fundamentally a political conflict.”2 The political conflict's contours, which serve as the backbone of McCoy's continuity argument, are explored throughout the monograph, with a particular focus on the “popular need for order,” that consistently provided justification for draconian measures taken on by American colonial and later American-supported authorities.3

These draconian measures made frequent use of surveillance, espionage, and what McCoy refers to as an information revolution, which was used to help bring down radical movements, leading to “radical leaders [beginning] to accuse their comrades of espionage, often on groundless suspicions,” thanks to disinformation and agent provocateurism.4 More damningly, this information revolution, in imperial boomerang fashion, was brought home to American shores and used against American citizens during the First World War. As McCoy writes, “a mix of emergency legislation and extralegal enforcement removed the restraints of the courts and Constitution that had protected Americans from surveillance and secret police for over a century,” all propped up by “police methods that had been tested and perfected in the colonial Philippines.”5 This expanded under the influence of Ralph Van Deman, who McCoy calls the “Father of the Blacklist,” and, thanks to a trove of documents in Van Deman's possession that amounted to “a massive private archive with thousands of classified documents.”6

This relates to the other previously underappreciated dimension to the discussion of American empire in general, and in its existence in the Philippines in particular: that is, the role scandal in the maintenance of power. As part of their growing police state in their new Philippine acquisition, “American colonials amassed files on their Filipino subjects rich in the most intimate details,” which ultimately “empowered American colonials to maneuver with magisterial authority, advancing native clients and conceding them power and position confident in the knowledge that they had weapons to destroy their creations.”7 Not only did this allow Americans to pacify their Filipino subjects—namely the ever-important elites—during their occupation of the archipelago until 1946, the methodology was adopted decades down the line within Filipino political society. As an example of how important scandal was for challenging power, McCoy recounts “a simmering scandal [that] erupted into a full-blown crisis when the opposition released a recording of a phone call the president [Gloria Arroyo] had made during ballot counting after the 2004 elections,” known as the “Hello, Garci” tape.8 The “politics of scandal,” as McCoy calls them, by no means was invented by the Americans, but it certainly became a norm under their rule, demonstrating that the imperial boomerang not only visited America's shores, but remained in place in the decolonized Philippines.

Policing America's Empire is nothing short of a monumental achievement in demonstrating the significance of the United States' near-constant presence in the Philippines—in both body and spirit—from 1898 into the early years of the 21st century. Significance for the Philippines themselves as well as the United States is demonstrated through the parallel and subsequent use of surveillance and scandal in order to pacify elements of both populations considered by authorities to be unruly, from the time of the First World War well into the modern day.

NOTES:

1. Alfred W. McCoy, Policing America's Empire: The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2009), 36.

2. Ibid., 36.

3. Ibid., 55.

4. Ibid., 193.

5. Ibid., 294.

6. Ibid., 318, 293.

7. Ibid., 125.

8. Ibid., 509.

It’s hard to avoid thinking that the American conquest of the Philippines during the Spanish-American War was a classic example of overreach. We only held the territory for less than half a century, and, having failed to make the investments to defend it from an aggressively imperialist Japan, ended up expending great blood and treasure to liberate it, only to relinquish control just a few years later.

We did get Subic Bay as a naval base out of it (which I think we still have), but it is true in many of these misadventures, the game was probably not worth the candle, especially in a nuclear-powered naval age. It arguably played a role in provoking the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

On the other hand, you might argue that the Filipinos were better off under us than they were under Japan, whereas the relative merits of Spanish colonialism versus American possession are, I suppose, debatable.

I imagine the Spanish had a lighter hand due to the school's military weakness.

We also spent substantial amounts of blood and treasure suppressing the independence movement.

As to the proposition that American suppression of Philippine resistance led to the surveillance state and the beginning of overclassification of government documents, perhaps it was a template, but certainly not one that we successfully applied to Vietnam. I would argue that there was a time in the United States was not comfortable with espionage and intelligence, back in the era when we disbanded the intelligence service that had been instituted during World War I, because according to one of our senior cabinet members, “gentlemen don’t read other gentlemen‘s mail “. Lord knows how much damage that attitude caused, but we became students of the British, who had always been masters of that sort of thing.

I would also argue that the Cold War was the real fuel that rightly spurred the US to develop more of an intelligence capability and more of a surveillance state. It’s undeniable now that we look back on the ‘40s and ‘50s and subsequent history that the Soviet Union had a significant undercover operation in the United States, including the theft of the atomic secrets that set the Cold War, mutually assured destruction paradigm in motion.

I would argue that the Communist sleeper network remains in place today and has penetrated our academic institutions and media.

Not too many people see that and those who don’t usually consider any assertion that it remains alive and well, operating globally in sort of zombie like fashion as evidence of lunacy on the part of those who try to point that out to the rest of the world, but the reality of it is that Putin resurrected a lot of that KGB and Comintern anti-capitalist apparatus and is using it against us to this day in concert with the Chinese.

Awesome article! I just posted about EDSA today that I thought you might like to check out :) https://open.substack.com/pub/liberterianoverwatch/p/anatomy-of-a-regime-change-2001-philippines?utm_campaign=post-expanded-share&utm_medium=web