The Not-So-Impossible Country: The Ever-Changing Study of Yugoslavism

This is the newest installment of historiographical work I have done for graduate school, this time taking a closer look at another favored topic of mine, the history of Yugoslavia, specifically about its first attempt at creating a unified kingdom. As long-time listeners of History Impossible know, this did not go well and many problems arose along the way. The question of why—and explaining how it was by no means inevitable—continues to this very day among many scholars of Yugoslavia and the phenomenon of Yugoslavism, which was the subject of analysis for this paper. The attempt to explain the first stab at a unified South Slav state began even before the disintegration of the Yugoslav state in the late 1980s and early 1990s, and while clarity has come as time has gone on, it remains a hot topic, thanks largely to the old wounds it tends to reopen and/or salt.

Anyway, please enjoy this newest piece of historiographical pedantry.

…

One might assume that national identity is only as complex as the nationality in question. However, this is an easily-made mistake. National identity comes from an intensely conscious and deliberate process, and oftentimes, even “simple” national identity (such as, say, that of the French) did not come about without dispute or conflict. States with varying ethnic groups, religious denominations, and clan loyalties are thus often seen as the “problem children” of stable national identities thanks to these supposedly inherent conflicts. Nowhere can this be seen more clearly than in many of the impressions of the former Yugoslavia. Thanks to its complex nature as a multi-ethnic, multi-confessional state and its eventual reputation as a state that broke apart and often warred with itself largely upon those lines—that is, ethnic and religious ones—there developed a lasting and flawed perception among media pundits, popular writers, and politicians that a South Slav state was always doomed to fail, with some even terming it an “impossible country,” to borrow the title of observer Brian Hall’s 1994 book.

Another common theme that arose from this perception was the assumption that what lit the flames of ethnic and religious conflict that rent apart this state was a confluence of “ancient hatreds,” something that historian Norman Naimark has ably refuted when he explains that these commentators “repeatedly cite [Bosnian novelist and poet] Ivo Andric’s The Bridge on the Drina to prove that the Balkans are endlessly violent,” despite the fact that this book’s context is relatively confined to the chaos of the Second World War. Indeed, the disintegration of a state by the name of Yugoslavia—which has occurred more than once—was an intensely modern phenomenon, with Naimark reminding readers that it was “rooted in the twentieth century history of nationalism and war in the Balkans and not—as so often proclaimed in the popular literature and press—in six hundred or more years of conflict.”

This is not to say that the disintegration of Yugoslavia and the wars that followed from the 1980s to the 1990s did not possess historical continuity; it most certainly did, as most scholars agree, thanks to the national idea of Yugoslavism. These scholars often point to the initial attempt at creating and maintaining a South Slav state—first the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, then turned into the Alexandrine Kingdom of Yugoslavia—as indicative of the kinds of dysfunctions the Yugoslav state would experience throughout its history, up to and including the official conclusion of its existence in June of 2006. What changed was how these dysfunctions were interpreted, from before the initial collapse in the 1980s until well after the official end in 2006. Therefore, the historiographical question with which this paper is concerned is as follows: How did Yugoslavism’s scholars’ interpretations of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes’ and Kingdom of Yugoslavia’s collapse change over time, particularly before, immediately after, and well after the final disintegration of Yugoslavia in the 1980s-1990s?

The most important theme shared among these scholars of Yugoslavism is one that disputes the aforementioned notions of inevitability and dismisses the canard of “ancient hatreds.” Where the scholarship changes has been in explaining how and why this is the case; in other words, the explanations for why the Yugoslav kingdom was not, in fact, doomed to fail from its very inception. Straddling the line between hindsight bias and diagnosing the dysfunctions found within the Yugoslav national project is a difficult one, but the scholars analyzed here each provide insightful and distinctive interpretations that point out the forks in the road in which choices were made by historical actors that were not conducive to the integrity of a Yugoslav national identity. The change in the scholarship over time reflects different weighting of different factors, ranging from a flawed constitutional construction to the legitimacy of the state to an actual lack of proper nationalist verve to sustain the energy needed to create a new state. In order to explore this trajectory, we must begin with scholarship that emerged before Yugoslavia even began its process of Balkanization.

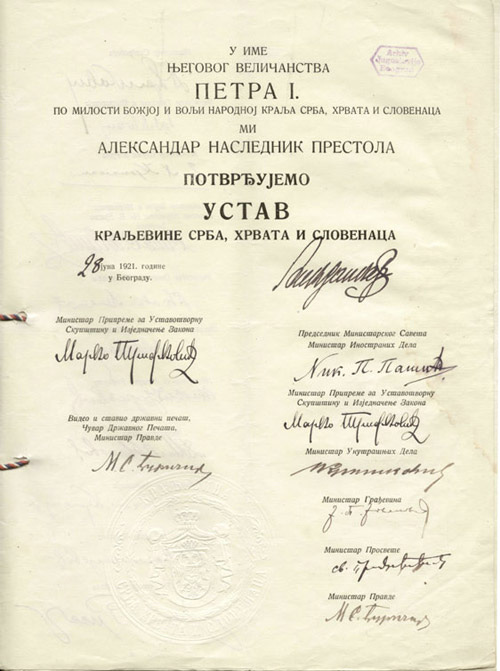

The first significant modern contribution to the study of the Yugoslav kingdom’s dysfunctions comes from the Croatian historian Ivo Banac in his 1984 work, The National Question in Yugoslavia: Origins, History, and Politics. This is partly due to its publication before the disintegration of Yugoslavia was truly underway, which essentially insulated Banac’s analysis from the temptation toward the hindsight bias with which so many future scholars had to contend. In this sense, Banac provided a blueprint for critically examining the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes and its later developments. Banac keeps the periodization of his analysis confined to the first three years of the Kingdom’s existence, beginning with “Yugoslavia’s flawed unification in 1918 and end[ing] with the adoption of the centralist constitution of 1921,” in order “to concentrate on the period that set the pattern for the subsequent development of the problem.”

Banac describes this pattern as one rooted in disenchantment thanks to a number of factors that happened to conspire against the effective unity of a South Slav state, at one point explaining that “the numbers—and therefore the influence—of each national group were dependent on its historical fortunes.” This way, Banac is able to explain that while there were plenty of historical precedents and collective memories fueling the division that occurred in the young Yugoslav kingdom, they were by no means fueled by “hatreds.” It was, instead, fueled by circumstance, largely determined by factors as varied as imperial influence, territorial expansion and contraction, and the creation of “invisible frontiers,” which resulted in a state of affairs in which “no national or religious group had an absolute majority.” Thus, no one could ever convincingly lay an ideological claim of representing the will of a Yugoslav people, though certainly it was not for lack of trying. Drawing from Miroslav Hroch’s sequence of national development, Banac also points out that “it is far more important to examine how faithfully each national ideology reflects the great issues of a nation’s history.”

When examining the different identities that existed within the borders of Yugoslavia, Banac argues, it is clear that many of these different national ideologies conflicted with one another, creating a situation in which the “Yugoslav national question was, more than anything, an expression of mutually exclusive nationalities.” This made it impossible for the Yugoslav state to meet the necessary criteria for a viable and internally stable state, and it was, according to Banac, reflected in both the Corfu Declaration of 1917 and the Vidovdan Constitution of 1921. In the case of the Declaration, the mutual exclusivity of both Nikola Pašić’ and Ante Trumbić’s visions for a South Slav state—of a Serbian-led centralist government and a co-equal federal state, respectively—demonstrated that not everyone was on the same page even before the Yugoslav kingdom was founded. In the case of the Vidovdan Constitution, it quickly became clear, thanks to invocations of Serbian folk imagination and history, that “an impression was made that the constitution represented the final triumph of Serb national ideology” in the creation of a supposedly unified and equal state of all South Slavs. This of course made it very unlikely for the new Yugoslav state to maintain legitimacy in the long-term.

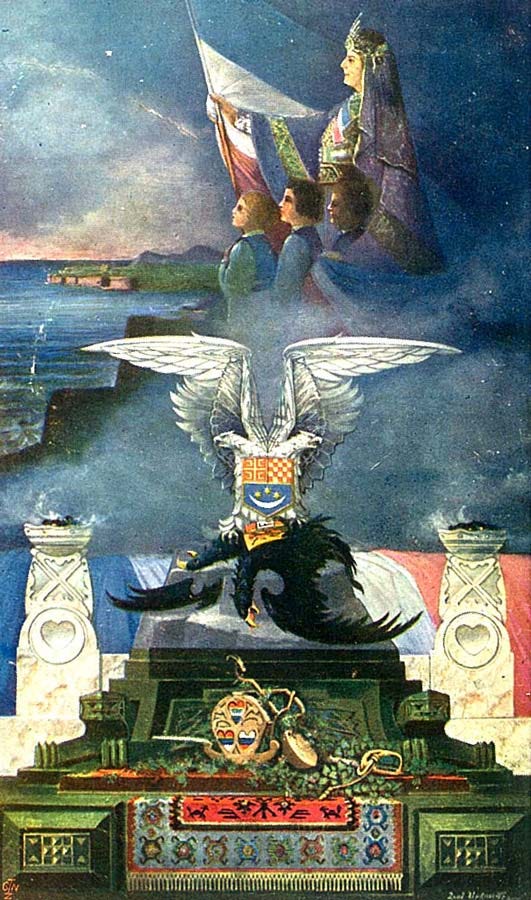

In 1996, in the midst of the death and suffering of the years following the Bosnian War, John R. Lampe published Yugoslavia as History: Twice There Was a Country, which picked up essentially where Banac’s work left off, this time with the benefit (and peril) of hindsight. Lampe manages to deftly avoid the presentist pitfalls created by persistent headlines in the news, and builds upon Banac’s argument of mutually exclusive goals. However, he explains Yugoslavia’s early (and thus contemporary) dysfunction from the perspective of competing expansionist nationalist movements, rather than “merely” national ideas. As he explains, the difficulty in building a viable South Slav state was made greater by “three romantic nineteenth century ideas for the creation of a unitary nation-state—Great Serbia, Great Croatia, and a Yugoslavia founded on the assumption that at least Serbs and Croats, and possibly all South Slavs, were one ethnic group.” Lampe argues that this was the result of a long history of imperial influence and criss-crossing, fragmented borderlands along with ideas of national identity developing at different times and places and under different circumstances, which created different national self-conceptions that often came into conflict with one another.

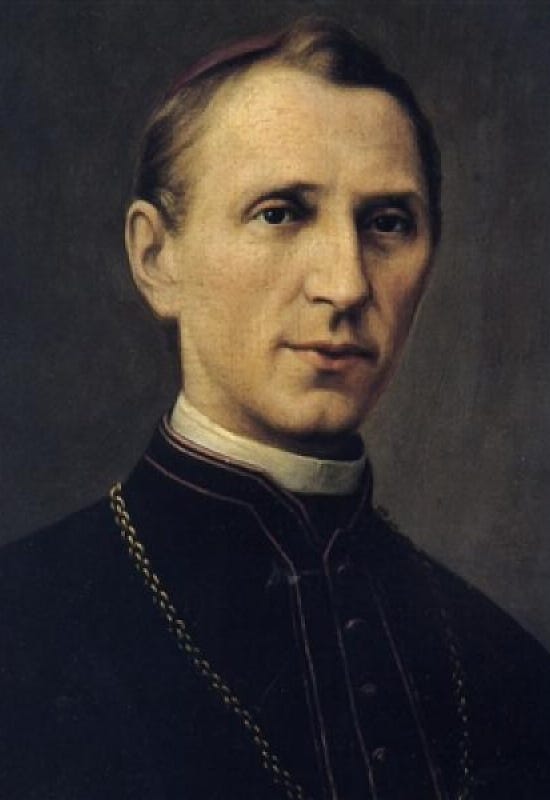

The expansionist nationalist impulse was already in place with many future Yugoslavs before the Corfu Declaration and the Vidovdan Constitution, with Lampe pointing to myriad examples of such rhetoric. For example, from 1906-1908, when Habsburg authorities granted authorization to Serbs, Croats, and Bosnians living within their imperial borders to organize along ethnic and political lines, each created their own nationalist school networks and formed ethnically-based political parties. They engaged in “‘tactical cooperation’” and “swept all of the seats” in the 1910 elections, but one could not ignore the proclamations of figures like Archbishop Josip Stadler in Sarajevo, who saw himself as “‘a full-blooded Croat with a German name,’ who saw Bosnia as a Croatian land.” This predetermined nothing, but it certainly foreshadowed the growing expansionist nationalist conflict Lampe describes as sucking the oxygen from the room after the formation of the first Yugoslav kingdom.

This could be seen in the debates that occurred during the ratification of the Vidovdan Constitution, in which “the name of the state; the recognition of religious freedom; the need for a second legislative chamber; and the nature of local administration” were argued over, with the last two issues “reveal[ing] more fault lines than the one dividing Serbia and Croatia.” Citing the analysis of American historian Charles A. Beard, Lampe points out that there was only a vague awareness of how any kind of government—a unitary or a confederal one—could actually operate, with nationalist priorities seeming to color the proceedings. This was reflected in the governing challenges that existed throughout the 1920s which occurred in part thanks to generational differences, in which older politicians—who dominated in the new parliament—“returned to lead regional Serb or Croat parties in the absence of younger men who might have favored country-wide, multi-ethnic parties had they survived the war.”

Lampe points out that the efforts of King Aleksandar during the kingdom years were well-intentioned, but were not as informed as they could be when it came to understanding the limits of royal influence on local governance. However, he also points out that as much as the king did sincerely wish to maintain the unity of his South Slav state, this came into direct conflict with the reality that “Serbian and Croatian politicians produced a political culture not unlike that of nineteenth century France,” in which “no party was large enough to win a parliamentary majority, and few of their leaders were tolerant enough of the other parties to work together for a coalition for long unless they were in opposition.” This incentivized greater centralization on the part of King Aleksandar and certainly does call to mind the centralizing efforts described both by historians Eugen Weber and Caroline Ford when discussing the formation of the modern French nation.

However, where it breaks with Weber’ and Ford’s analyses is the fact that, despite not necessarily seeing themselves as “French,” per se, the people all over the French countryside did not see themselves as something else entirely the way many Croats, Bosnians, Slovenes, and others did in the Yugoslav kingdom. According to Lampe, “a multi-ethnic state had little chance of survival by the 1930s,” after King Aleksandar dissolved the parliament and established the royal dictatorship.14 After this controversial decision, the popularity of Yugoslavism increased, but only among the Serb population of the kingdom, and thus created a perception among the non-Serb populace that Yugoslavism was simply a trojan horse for a “Greater Serbia,” despite Aleksandar’s opposition to the radical nationalists of the country. The problem was that no matter what the intentions were—good or otherwise—open attempts at creating “Greater” ethnostates or invocations of a unified Yugoslav state were seen by their opponents as completely illegitimate.

The question of legitimacy deeply informed Sabrina Ramet in her massive book, The Three Yugoslavias: State-Building and Legitimation, 1918-2005, which sought not just to chronicle the kingdom years of Yugoslavia, but also the civil war that rent the country apart during World War II, Tito’s socialist republic, and the disintegration of the state that officially lasted until 2006. Ramet makes it clear, however, that the same problem of illegitimacy was at the root of each failure of a Yugoslav national project, including its first incarnation in 1918. The specifics certainly matter, but Ramet’s persistent theme returns to the idea of state legitimacy. As she writes, “There was [...] a deeper crisis which ran through Yugoslav history in 1918-2004, a permanent crisis rooted in its elites’ failure to resolve the dual challenges of state-building and legitimation.” By casting the dysfunction found in early Yugoslav history as part of a longer, wider history that covers its entire existence, Ramet runs the risk of overstating her case, but effectively explains that there were common problems with state-building and legitimation across the “three Yugoslavias,” as she puts it. Defining state legitimacy as a system of government that “protects human rights, including but not limited to freedom of association and freedom of the press, ensures citizens’ access on an equal basis to quality education, work commensurate with qualifications, and salary commensurate with work, and fosters the moral excellence of its citizens,” Ramet argues that the Yugoslav kingdom (and other incarnations) did not meet this criteria.

In focusing on state legitimacy, Ramet avoids the deterministic trap of overrating multi-ethnic and multi-confessional factors when explaining the dysfunction of the Yugoslav kingdom, reminding us that such internal divisions “may even contribute to breaking down stereotypes and narrow provincialism,” while also acknowledging that they often “affect the way in which crises in illegitimate systems are played out.” Drawing from Ernest Renan’s concept of a nation, she points out that the Yugoslav kingdom did face a problem of division, but not one related to ethnicity or religion; specifically that “Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes did not share a common recollection of the past,” and that this resulted in the different groups “[looking] to different state traditions” and “[entering] the kingdom with rather different political expectations,” all made more difficult by the fact that Wilsonian principles of national self-determination could not overcome “the empirical fact of language difference” creating natural barriers.

The subsequent problems faced by the kingdom throughout the 1920s and 1930s often began with notions—often from Croats—of subjective illegitimacy, which ultimately were proven to be objective, per Ramet’s definition, when Serb-led kingdom authorities often cracked down on non-Serb dissent. This crisis of legitimacy manifested in many other ways, particularly with an appearance of poor decision-making. As Peter Troch points out, “It soon became clear, however, that Aleksandar’s death had left the ruling political elite without any legitimacy,” further explaining that the Prince-Regent Pavle’s subsequent decision to have Milan Stojadinović form a new government “meant the actual end of the Royal Dictatorship of King Aleksandar and of integral Yugoslavism as its official national ideology.” Ultimately, Ramet argues that “the Vidovdan [Constitutional] system was objectively illegitimate,” thanks to its many failures to adhere to objectively legitimate standards, and thanks to Serb political elites (and possibly the monarchy) believing that “the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes represented an expansion of the Kingdom of Serbia, and it was therefore, in their view, ‘logical’ that Serbs controlled the levers of power.” Echoing the argument advanced by Lampe, the problem was one of expansionist nationalism.

The view that nationalism presented a fatal problem to Yugoslavia has since become more nuanced. In 2023, nearly two decades after the official end of Yugoslavia, the historian Božidar Jezernik argued in his book Yugoslavia Without Yugoslavs: The History of a National Idea that nationalism was indeed the problem facing the Yugoslav kingdom, but not in the way previous scholars had suggested. Instead of “an excess of history or an overwhelming social and political weight that the young nation could not throw off” or “nationalisms too vicious to for disputes to be settled at the ballot box,” the problems facing Yugoslavia “lay not in a surplus but rather in an absence of nationalism.” The problem, in essence, was that there were not enough Yugoslavs to maintain the idea of a Yugoslavia, while there were plenty of Serb and Croat nationalists to form their own ideas of a Greater Serbia or Greater Croatia. Had there been more Yugoslavs, these nationalist forces would have made little difference in the effort to make Yugoslavism into a reality.

Jezernik supports this argument by turning the clock back even further than the other scholars analyzed here and looks to chart the actual history of Yugoslavism as an idea. However, like the previous scholars, he identifies different conflicts that naturally arose from competition over the Yugoslav idea, which originated well before the formation of the Yugoslav kingdom in 1918, and demonstrates that they indeed had rippling effects across time. As Jezernik explains, this likely came down to the uncertainty that was associated with the Yugoslav idea in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century, writing that “the answer to the question of whether there is one Yugoslav nation or several such nations was not as clear [...] as it is today.” This uncertainty was made worse by the distrust of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which Jezernik points out is the less-appreciated source of suspicion and even hatred for the idea of a “Greater Serbia,” a suspicion which its future South Slav peoples would essentially inherit. This is supported by the scholarship of Dušan Fundić, who in comparing the national ideas of Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia, points out that “contrary to the self-proclaimed nation-state ideologies they insisted on, Czechoslovakia and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes [...] should primarily be analyzed as heterogeneous patchworks of several imperial legacies,” which left many similar lasting impressions and effects.

The Yugoslav patchwork was reflected in what was ultimately a disorganized formation of the kingdom in 1918, made disorganized by the differing intentions and priorities possessed by the elite representatives of the various national groups. Had “the fathers of a newborn nation [...] worked together as a well-coordinated team, thinking through as many steps as possible in advance,” and developed a coherent and unified Yugoslav nationalism with which most citizens of the new kingdom could get behind, the dysfunction experienced by the kingdom would not have reached the extreme problems it eventually did. This revisionist approach taken by Jezernik, while potentially controversial, is persuasive because it makes the strongest case against the deterministic fallacies and problematic invocations of “ancient hatreds” that polluted the discourse surrounding Yugoslavism in the popular press and among politicians. Jezernik acknowledges that there were indeed previously-set precedents many generations before the formation of the kingdom, but the problem was less that these precedents were negative ones and more that “memory was short” and allowed for counterproductive nationalistic traditions like those of “the Serbian elite [who] began to spread the cult of [the 1389 Battle of] Kosovo, making it a source of inspiration and hope [exclusively for Serbs].” In Jezernik’s view, this was just one example among many of particularist nationalisms that essentially distracted the South Slavs from the project that had the potential to truly make them a unified people.

The historiography of Yugoslavism has taken many different turns over the years, both before and after the disintegration of the country was complete. Thanks to the efforts of scholars like Banac and later Lampe, norms of resisting the determinism that existed among the wider public and popular press were effectively set, and different interpretations were able to proliferate and add to the conversation. This is important not because it necessarily clarifies the already complex situation that defines the former Yugoslavia, but rather because it demonstrates the complexity that is inherent to all national projects and the difficulties that are present in all of them as conscious efforts. The problem is not that there are national ideas that are doomed to fail, as much as there are national ideas whose execution has not been ideal and will thus experience dysfunction and, quite probably, failure. Identifying failures is among the best ways to inoculate oneself against those failures from occurring in the future. Where some national ideas succeeded for nearly 250 years—such as that of the United States, however imperfectly—some failed after a mere two decades, as was the case with the Yugoslav kingdom. It was never preordained to have an unhappy ending, even when, to use the words of Božidar Jezernik, “God became a Yugoslav,” and the people of the kingdom began to resemble “three quarreling brothers who could agree only to overlook their similarities and view their differences as essential.” It is a warning any nation, regardless of homogeneity or heterogeneity, would do well to heed.

…

Bibliography

Banac, Ivo. The National Question in Yugoslavia: Origins, History, Politics. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1984.

Fundić, Dušan. “Searching for a Viable Solution: Yugoslav and Czechoslovak Nation-Building Projects in the 1930s.” Balonica 54 (2023): 151-173.

Jezernik, Božidar. Yugoslavia Without Yugoslavs: The History of a National Idea. New York: Berghahn Books, 2023.

Lampe, John R. Yugoslavia as History: Twice There Was a Country. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Naimark, Norman M. Fires of Hatred: Ethnic Cleansing in the Twentieth Century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001.

Ramet, Sabrina P. The Three Yugoslavias: State-Building and Legitimation, 1918-2005. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2006.

Troch, Pieter. “Yugoslavism Between the World Wars: Indecisive Nation Building.” Nationalities Papers 38, no. 2 (2010): 227-244.