The Tragedy and Farce of the Short Century

A Review of Eric Hobsbawm's The Age of Extremes

The attempt to characterize or even diagnose the twentieth century is often done in the context of its violence thanks to the World Wars and the inherent threat of nuclear apocalypse that hung over the years of the Cold War. This is understandable, given the unprecedented scale of violence that occurred during the wars made possible by advancing technology, but many scholars have looked at the increasingly common role of ideology in creating such circumstances. As the century reached its final decade, many scholars and writers began to reflect on the century that was coming to an end as a way of determining what was to come.

This trend began to manifest in 1989 with the publication of Francis Fukuyama’s infamous article, “The End of History?”, which argued the fall of communism was paving the way for a relatively stable liberal, democratic future with no meaningful ideological alternative. In discussing a supposed “end of history,” Francis Fukuyama explains that with the end of the Cold War in 1989 and the liberalizations occurring within the Soviet Union under Mikhail Gorbachev, the final viable permutation of ideological development had revealed itself: liberal democracy. As Fukuyama explains, the end of history is “the end point of mankind’s ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.”1 Fukuyama does not outright say that there will be no other challenges (or “histories,” so to speak) that will challenge this new, final paradigm, but he is also clear that no viable alternative has revealed itself on a civilizational scale.

All alternatives were dead ends, Fukuyama argues: fascism had been completely discredited since 1945, China clearly did not follow the Marxist-Leninist paradigm anymore, and because the only other great power, the Soviet Union, was going through a process of liberalization, all that was left was liberalism. An important thing to realize is that Fukuyama is the first to admit that the idea of an “end of history,” as he is describing it, is not a novel concept. In fact, he points to eighteenth and nineteenth century writers like Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and Karl Marx to show that many have claimed that history would one day “end.” But his argument’s greater influence is the writer Alexandre Kojève, who believed that history had reached its end with the conclusion of the Second World War, after which “no struggle or conflict over ‘large’ issues” could exist, with all that remaining being “primarily economic activity.”2

Fukuyama’s argument for an “end of history” has been savaged in the years since its publication, thanks largely to the benefit of hindsight making his claims come off as naive, but taking his arguments in the context of their time, it is understandable that he would see things the way he did. It is true that some of his arguments do not age well at all, particularly his dismissal of neoconservative commentator Charles Krauthammer’s claim that without its Marxist-Leninist ideology, Russia’s “behavior will revert to that of nineteenth century imperial Russia,” and his assumption that Gorbachev’s attempt at resurrecting Leninism are “Orwellian doublespeak,” going against the evidence later presented by scholars like Vladislov Zubok, shown in his magisterial work on the disintegration of the USSR, Collapse: The Fall of the Soviet Union.3 Without digressing much further into the historiographic weeds, Zubok’s work does much to disabuse us of the notion of Gorbachev being a cynical operator and, in fact, a product of post-Thaw Soviet cultural developments in which Stalin—and not communism itself—was the aberration, and the goal was to return to what Lenin intended for the new communist state in 1917.

However, Fukuyama deserves more credit for understanding where China’s development under Deng Xiaopeng was heading—a market-driven command economy of sorts; something closer to Mussolini’s corporate fascism than anything envisioned by Karl Marx—as well as acknowledging the challenges facing liberalism in the form of Islamism and internal nationalism. Fukuyama does discount the idea of expansionist nationalism at the peril of his credibility (especially with hindsight vis-a-vis later events in the Yugosphere in the 1990s and, again, with Putin’s Russia and its new era of imperialist expansionism), but he provides a good reality check when it comes to the civilizational threats posed by Islamism and nationalism; these things are serious and can have provably threatened internal stability in various nations, as we have seen in the thirty-six years since “The End of History?”’s original publication, but having lost the other pole of the Cold War’s bipolar world, assuming Western liberalism’s unipolarity was a fair assumption.

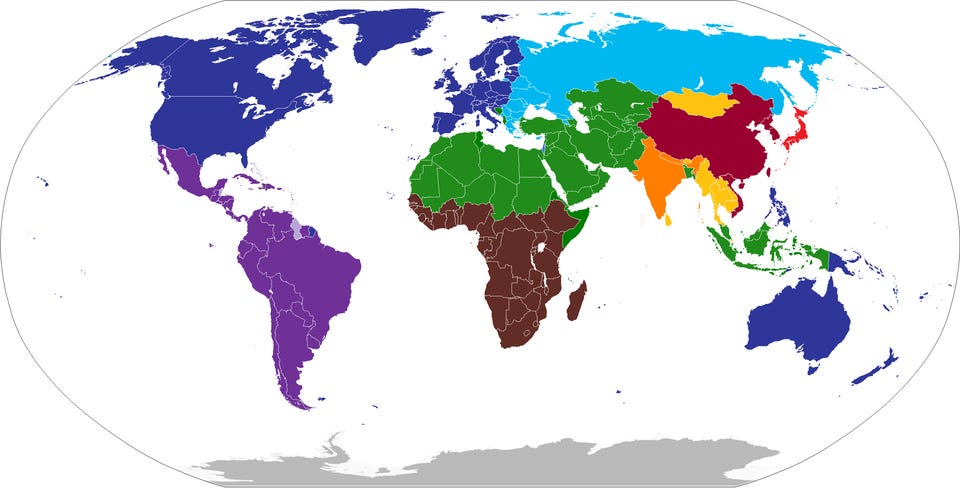

Standing in contrast with Fukuyama was his old professor, Samuel Huntington, whose equally infamous 1993 article “The Clash of Civilizations” (and one that was likely written in response to Fukuyama’s own) argued that the end of ideological conflict was heralding a far darker and more existential future in which entire civilizations would compete for dominance over the globe. According to Huntington, the world order, especially after the fall of the Soviet Union, is defined by the interaction of various civilizations, which includes the West, but also other cultures, including Confucian, Islamic, and Slavo-Orthodox, to name just a few. Whether these categories actually constitute “civilizations” as Huntington describes them or not is less relevant than the fact that they all contain fundamental differences; as Huntington writes, “differences among civilizations are not only real; they are basic.”4

As Huntington would have it, because these differences are products of unique cultures and centuries of history, they largely cannot be reconciled in such a way that precludes conflict. While Huntington is careful to note that conflict due to civilizational differences is not guaranteed and that violence is not inherent, he makes it clear that these differences between the world’s seven or eight civilizations are so fundamental that a true multiculturalism is essentially impossible. Huntington also believes that clashes between civilizations are almost certainly inevitable in the modern era—contrasting with Fukuyama’s more liberal, multicultural view—because of several factors. For example, local identities have started to become separated from individuals; as he puts it, “the nation state as a source of identity” has been fundamentally weakened and thus strengthens the more fundamentalist parts of societies as identity anchor points.5

In addition, Huntington argues that the shrinking of the world leads to greater interaction between civilizations, and a greater effort to emulate the West’s success at achieving such great influence, as well as an increase in “economic regionalism.”6 However, he does also describe conflicts that “occur between states and groups within the same civilization,” while also claiming this is less likely to occur in the future.7 Huntington supports his claims with the writings of other writers and scholars, such as Indian journalist and later member of Parliament M.J. Akbar and the renowned Orientalist and intellectual Bernard Lewis with their predictions of Western-Islamic conflict and explanation for the origins of “Muslim rage” against Judeo-Christian culture, as well as Murray Weidenbaum and his explanation of the growth of the East Asian economic bloc in the late twentieth century, to use two prominent examples.8

Like Fukuyama, Huntington’s argument has elements that are compelling, as well as elements that do not age well. However, the “‘us’ versus ‘them’ relation existing between themselves and people of different ethnicity or religion” he identified within the framework of clashing civilizations did and would indeed continue to hold true in various contexts as the years progressed after his initial writing.9 For example, it is undeniable, based on much of the writings from figures like Osama bin Laden such as his 2001 open letter published (and later removed in 2023) in the Guardian, and the rhetoric of figures like George W. Bush in the wake of events like 9/11 that nations and forces were viewed in this way from either side, whether due to religious fundamentalism or a fundamentalist belief in the supposed civilizing mission of American democratic supremacy. Huntington seems to believe in this divide and does little to dissuade his readers from believing it as well, but his civilizational framing is, at least for my tastes, far too deterministic and does not leave room for the nuance required to understand why disparate cultures have and continue to have common interests and support one another.

It is therefore clear that both articles reflected an awareness that an old era had passed, and that it had been dominated by ideological conflict, but their authors seemed to have little interest in interrogating their own certainty.

Filling that void was the unapologetic Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm, who, in 1994, provided definition and clarity to what he called the “Short Century” of the previous eight decades in sweeping detail, with his book The Age of Extremes: A History of the World: 1914-1991. Now, one might not expect someone like me to make this claim, but to my mind, the best “big history”—that is, large scale diagnosis—of the Twentieth Century did not come from a neoliberal or neoconservative historian (I will be the first to admit, likely much to the chagrin of some of you reading, that I often tend towards those schools of thought when it comes to history), but rather, from a Marxist, and one of a truly classic vintage at that: Eric Hobsbawm. This is not to say that I did not find certain assertions made by Professor Hobsbawm in his book that we are about to examine to be particularly troubling, with his refusal to label the Soviet Union as an actual totalitarian system being perhaps his most noteworthy, when he wrote the following passage:

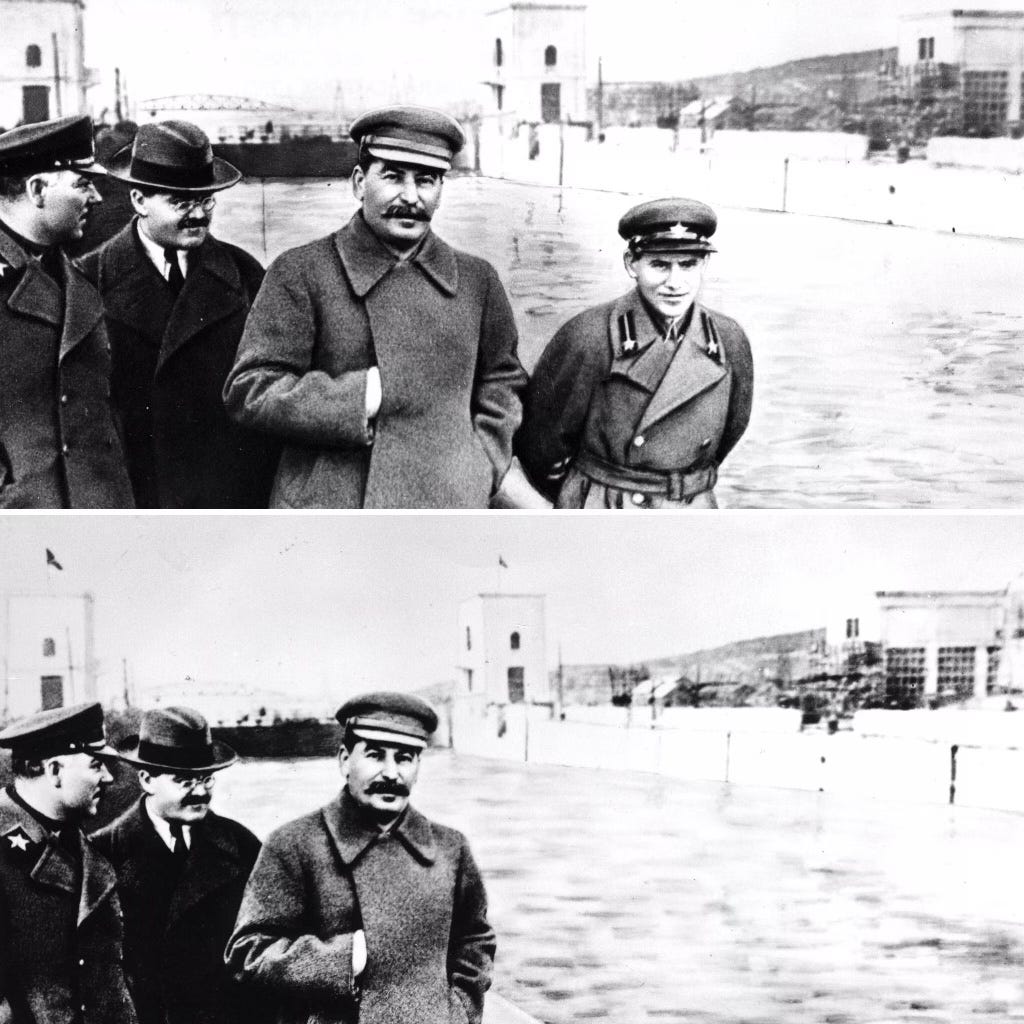

Brutal and dictatorial though it was, the Soviet system was not “totalitarian,” a term which became popular among critics of communism after the Second World War, having been invented in the 1920s by Italian fascism to describe its objects. Hitherto it had been used almost exclusively to criticize both it and German National Socialism. It stood for an all- embracing centralized system which not only imposed total physical control over its population but, by means of its monopoly of propaganda and education, actually succeeded in getting its people to internalize its values. George Orwell’s 1984 (published in 1949) gave this Western image of the totalitarian society its most powerful form: a society of brainwashed masses under the watchful eye of “Big Brother,” from which only the occasional lonely individual dissented.

This is certainly what Stalin would have wanted to achieve, though it would have outraged Lenin and other Old Bolsheviks, not to mention Marx. Insofar as it aimed at the virtual deification of the leader (what was later shyly euphemized as “the cult of personality”), or at least at establishing him as a compendium of virtues, it had some success, which Or- well satirized. Paradoxically, this owed little to Stalin’s absolute power. The communist militants outside the “socialist” countries who wept genuine tears as they learned of his death in 1953—and many did—were voluntary converts to the movement they believed him to have symbolized and inspired. Unlike most foreigners, all Russians knew well enough how much suffering had been, and still was, their lot. Yet in some sense by virtue merely of being a strong and legitimate ruler of the Russian lands and a modernizer of these lands, he represented something of themselves: most recently as their leader in a war which was, for Great Russians at least, a genuinely national struggle.

However, this problematic assertion—along with Hobsbawm’s later shocking admission that he believed the proven death and destruction created by the Soviet Union was not enough to get him to reconsider his Marxist beliefs—surprisingly does little to dampen the overall diagnosis and analysis he provides of the twentieth century’s depraved, violent character, as well as the relatively prescient awareness he had of where things were going as of the book’s publication in 1994. Credit should be given where it is due, even when it is going to a Stalinist like Hobsbawm most certainly was. The only reason there was any prescience at all is because of how keenly he observed the eight decades that had just passed.

In short, Hobsbawm argues, the purpose examining the Short Twentieth Century is “to understand and explain why things turned out the way they did, and how they hang together,” and thus see it for what it was: “a century of religious wars.”10 In doing so—that is, understanding the fundamentalist character of the Short Twentieth Century—one may perhaps understand how the future, according to Hobsbawm, would be one defined by our “unfortunately accelerating, return to what our nineteenth-century ancestors would have called the standards of barbarism”; it became, as he later concludes, “the atmosphere which urban humanity at the end of the millennium learned to breathe.”11 For anyone, including a civilization (to use Huntingtonian language), to be able to breathe barbarism, one must have been inculcated and conditioned by barbarism, and as Hobsbawm would have it, there is no better way to define the Short Twentieth Century.

Hobsbawm makes it clear that the bang with which the Short Twentieth Century began—that is, the First World War—was not driven by ideology, but rather by the notion of infinite growth. It was, in fact, “waged for unlimited ends,” because, “In the Age of Empire, politics and economics had fused.”12 The chaos and fury of the First World War set the table for the birth of the ideological global conflict, first with the October Revolution and the birth of the Soviet Union, and then the rise of “the revolutionaries of counterrevolution” that made up fascism and National Socialism in Italy and Germany, respectively.13 Despite the rise of ideology (or perhaps because of it, especially in the case of communism’s vision of world revolution), the world was “no longer Euro-centred and Euro-determined,” which was made all the clearer by the rise of the Third World following the end of the Second World War and the end of empires, though Hobsbawm does note that the Great Depression and failure of liberal capitalism was “a landmark in the history of anti-imperialism and Third World liberation movements.”14 In short, nothing would ever be the same after the period Hobsbawm calls the Age of Catastrophe, but not necessarily in the way other commentators at the end of the Short Twentieth Century would assume.

The middle of the Short Twentieth Century began with what Hobsbawm calls the “Golden Age,” though not in the way that later commentators would necessarily have it. Instead of one “single homogeneous period in world history,” that begins in 1945 and ends in 1989, the era that came to be known as the Cold War “fall into two halves, the decades on either side of the watershed of the early 1970s.”15 There were attempts made by both the United States and the Soviet Union—the two belligerents of the “very peculiar [Third World War]”—to secure their power over vassal states and smaller world powers, though Hobsbawm makes the curious claim that “the ‘communist camp’ showed no sign of significant expansion between the Chinese revolution and the 1970s,” which does little to countenance the military expansionism of the Soviet forces into places like Czechoslovakia.16 However, his point is well-taken in that the ideological spread of communism did little expansion during this period of time. This tracks with his later claims about the true appeal of communism in the Third World, which was, as it would turn out, limited and often confined to a more nationalist scope.

Making good use of economic data and first-hand accounts, Hobsbawm charts the changes occurring throughout the First World during and following the Golden Age, particularly with the decline of peasant classes, the rise in the importance of higher education, the emergence of women in the labor market, and the related cultural shifts that began to manifest in the 1970s. While he compellingly explains that the notion of “a collapsing working class” during this period is an “illusion,” he does point out there was “a crisis not of the class, but of its consciousness,” resulting in what would eventually be recognized as the individualism that defined the world of the 1990s (and arguably beyond).17 Beyond these shifts in the First World, however, there were profound and revealing shifts in the Third World that were both independent of and conflicted with the First and Second Worlds of the Short Twentieth Century.

While ostensibly the First World was defined by capitalism and the Second by communism, the Third World was defined by “a distinctly new phenomenon,” in which military coups became the norm thanks to being “the product of the new era of uncertain or illegitimate government.”18 This development, a product of the decolonization process and the rise of national consciousness (often filtered through a communist or socialist lens, as was the case with states like Vietnam), thus made First and Second World military intervention into the Third World “far more inviting, especially in new, feeble and often tiny states.”19 This was part of a “wave of rebellion [that] swept across all three worlds,” but ultimately, Hobsbawm contends, lead to a situation in which “the revolutions of the late twentieth century thus had two characteristics: the atrophy of the established tradition of revolution” and “the revival of the masses.”20 This was, per Hobsbawm, symptomatic “of the growing barbarization of all three worlds,” that would come to define the end of the Short Twentieth Century, forming one of the most compelling parts of his overall argument.21 By the end of this eighty year period, inequality became massive not just between the First and Third Worlds (to say nothing of the collapses facing the Second World in the late 1980s), but also between members of the First World itself.

This inequality, not to be saved by what Hobsbawm very subjectively sees as the vulgarization of art and culture, as well as the insufficiency of scientific and technological development to save us from his foreseen barbarization, could be seen in the failure of the remaining ideological structure in place in the 1990s—that of neoliberal capitalism, which started to become the First World’s raison d’être during the post-1945 Golden Age—to address the reality that “human collective institutions had lost control over the collective consequences of human action.”22 The consequences of this, Hobsbawm argues, is that globalized competition will result in “one or both of two consequences [that] must follow [as of 1994]: the transfer of jobs from high-wage to low-wage regions and (on free-market principles) the fall of wages in high-wage regions under the pressure of global wage competition.”23

This could only have happened with the continued inequality between the First World and the Third, and the victory of the First World over the Second; the division of the globe into such worlds was only accomplished through the dominance of ideology and what Hobsbawm calls “an era of religious wars, though the most militant and bloodthirsty of its religious were secular ideologies of nineteenth-century vintage, such as socialism and nationalism, whose god-equivalents were either abstractions or politicians venerated in the manner of divinities.”24 And this was only possible thanks to the zero-sum attitude developed during the Age of Empire, bolstered by similar attitudes toward infinite growth on display at the end of the Short Twentieth Century.

The greatest trouble facing the world is that no one has the memory of such developments; that is the third and final transformation that brought the Short Twentieth Century to a close. Ultimately, Hobsbawm argues, this “third transformation, and in some ways the most disturbing,” in which the links between previous and subsequent generations have undergone “snapping […] that is to say, between past and present.”25 There was no end of history or a grand clash of civilizations as the Short Twentieth Century came to an end; there was the victorious forces of capitalism, which had indeed proved itself to be “a permanent and continuous revolutionizing force.”26

Neoliberal political scientists such as Francis Fukuyama have admitted an “end of history” was a depressing thing, he never fully elaborated on why this might be the case, and even, perhaps facetiously, suggested that the “very prospect of centuries of boredom at the end of history will serve to get history started once again.”27 Conversely, pessimistic conservative historians like Samuel Huntington have suggested that a retreat of ideological and a deterministic return to increasing “civilizational consciousness”—firmly rooted in an innate knowledge of a deep, shared (and conflicting) past—lay in our future, in which “violent conflicts between groups in different civilizations are the most likely and most dangerous source of escalation that could lead to global wars.”28

However, Eric Hobsbawm made it very clear that something far more depressing, and far less dramatic, lay in store for the future of humanity after the age of extremes had passed: a complete divorce from history, in which everything exists in the self-interested present, with our only guide being our century-long learned adaptation of breathing barbarism. Perhaps Hobsbawm would disagree, but when reading his words, it appears that he was simply restating the implications made by figures like Fukuyama and Huntington in plainer, perhaps even more compelling terms.

Notes:

1. Francis Fukuyama, “The End of History?” in The National Interest 16 (Summer 1989), 4.

2. Ibid., 5.

3. Ibid., 13, 15.

4. Samuel P. Huntington, “The Clash of Civilizations?” in Foreign Affairs 72, no. 3 (Summer 1993), 25.

5. Ibid., 26.

6. Ibid., 27.

7. Ibid., 38.

8. Ibid., 28, 32.

9. Ibid., 29.

10. Eric Hobsbawn, The Age of Extremes: A History of the World: 1914-1991 (New York: Random House, 1994), 3, 5.

11. Ibid., 13, 457.

12. Ibid., 29.

13. Ibid., 117.

14. Ibid., 34, 204.

15. Ibid., 223.

16. Ibid, 226, 227-228.

17. Ibid., 302, 305.

18. Ibid., 348.

19. Ibid., 349.

20. Ibid., 444, 456.

21. Ibid., 457.

22. Ibid., 565.

23. Ibid., 572.

24. Ibid., 563.

25. Ibid., 15.

26. Ibid., 16.

27. Fukuyama, “The End of History?”, 18.

28. Huntington, “The Clash of Civilizations?”, 48.

I really need to read this. Sounds like just what I need to start the new year. Srsly