Why the Abortion Debate Is (and Will Always) Be Different

Some thoughts on the biggest American culture war flashpoint

With the confirmation that the Supreme Court of the United States' draft opinion on the question of the Roe v. Wade (1972) and, by extension, Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992), decisions is indeed legitimate, abortion has finally left the rhetorical coma it entered over a decade ago and begun to show its face yet again. Within 24 hours, violence had already erupted on the streets of Los Angeles, resulting in at least one police officer becoming injured, and quite possibly showing the firestorm that is to come if (or once) this court ruling comes to pass, and especially if (or once) state laws begin to reflect such a passage and progressives' worst fears begin to come to pass. Despite the constant warnings from advocates since the inauguration of Donald Trump in 2017 and the massive, record-breaking Women's March (not to the mention the constant invocations of The Handmaid's Tale through cosplay), progressive pro-choice advocates and supporters clearly seem and described themselves as shocked by the contents of this leak, though certainly they have and will find new verve with which to protest. We have seen how this plays out before, whether it has to do with transgender issues or the unfair treatment of black Americans at the hands of the police. And yet, when one begins to examine the landscape and, more importantly, the data, a very different, much more complex picture begins to appear that seems to transcend simple partisan politics surrounding social issues.

The attitudes of Americans on every major, highly-publicized social issue of the last 75 years have meaningfully shifted towards one direction: acceptance of changing social standards. Despite a 1963 Gallup poll suggesting that 78 percent of white Americans would move out of their neighborhood if several black families began to move in, in the two decades that followed Brown v Board of Education (1954), support for any law segregating whites and blacks from one another plummeted to less than 15 percent, according to a general social survey published by Princeton University in 2012. By the 1980s, it was less than ten percent, and by the 21st century, no one was even asking questions regarding segregation anymore.

The same holds true for interracial relationships and marriage. In the decades following the landmark case of Loving v. Virginia (1967), attitudes toward interracial coupling continued to warm. According to data collected by the Pew Research Center, while the approval of interracial dating between whites and blacks hovered at around 48-50 percent in 1987, but as soon as the 80s gave way to the 90s, that number began steadily climbing where it peaked in 2009 at 83 percent of approval. As of 2017, the rates of acceptance reported by Pew continue to climb with rates of dissent continue to decline. Much of the data collected in these surveys depended largely on the age of the person being polled, with lower rates of acceptance appearing with older age cohorts. This is unsurprising but it also likely reflects why so much attitudinal change is happening as millennials and Gen Z begin to take their place as the stewards of American culture.

Perhaps the finest and most salient point on attitudinal change that can be made, however, is in the case of same-sex marriage acceptance. In 1997, Gallup reported that a mere 27 percent of Americans supported the idea of same-sex marriage. That climbed to 35 percent in 1999 (perhaps not coincidentally the year following the premiere of the hit gay-friendly sitcom Will and Grace) and then continued its ascent to 60 percent into the 2010s with the passage of Obergefell v. Hodges (2015). From there, it only continued to grow, peaking in 2021 with Gallup reporting that a whopping 70 percent of Americans supported same-sex marriage, which included a majority of Republican voters. Less than two decades before, the GOP was the bastion of moral panic regarding the “gay agenda” and while in 2022 there seems to be a bit of a resurgence of gay panic in the form of “groomer discourse”, it's apparent that acceptance of same-sex marriage is becoming a societal norm. And while it is certainly been gradual, like all other issues previously covered, it's hard not see the attitudinal shift toward same-sex marriage acceptance as anything other than meteoric, especially when considering the last Democratic candidate for president only came around to supporting same-sex marriage two years before its effective legalization.

These trends appear to be ironclad, and with all of them being considered to be part of progressive causes, one could be forgiven for believing that the arc of American social history is indeed toward this notion of progress. And yet, as has been revealed with the recent draft opinion from the SCOTUS (and much more), things aren't that simple. If one bought into this understandable presumption that American social life is marching in lockstep toward progress, they could also be forgiven for thinking that when they see mass protests in places like Los Angeles, or recall the three-to-five-million-strong Women's March in 2017, or likely seeing the even larger protests that are likely to come, that this is yet another settled social issue that reactionary fascist holdouts are weaponizing against all women. “We've progressed past this!” they must think. “Just look at the gains made by LGBTQ people! And all minorities!” For those that believe this, however, they are bound to be in for a rude awakening when they actually look at the data surrounding the hot-button topic of abortion.

In 2021, Gallup put out a report that showed something truly fascinating: that apart from some peaks at 50-51 percent in 2006 and 2015, Americans who considered themselves pro-choice have consistently hovered around 48-49 percent from 2017 until 2021, with pro-life attitudes reflecting a similar rate. It was 1995 that the last major difference and possible notion of “progress” was reported, with 56 percent of respondents calling themselves “pro-choice” and a surprisingly small 33 percent calling themselves “pro-life”. Even more interestingly, the data, all the way into 2021, suggests that a mere 32 percent of respondents believe that abortion is acceptable in all cases, while the “acceptable in some cases” responses totaled at around 48-52 percent, and “illegal in all cases” rarely ever topping 20 percent. And yet, when boiled down to the fundamental question of whether one is “pro-life” or “pro-choice” the data is clear: while certain subtleties exist within the data (namely when during pregnancy that termination is considered acceptable) overall attitudes on abortion have not changed in decades.

This, of course, leads us to the question of why? Why have all those other social issues previously mentioned moved the needle on Americans' overall attitudes and why has this not? It is hard to say for certain, but much can be speculated. According to Pew Research, 67 percent of adults who look to religion to assist them in determining what is right and wrong believe abortion should be illegal in most or all cases. With the exception of Jewish respondents, all groups polled who look to religion to guide their moral compass—including the “religious none's”—had a plurality, if not handy or even overwhelming majority in favor of making abortion illegal in most or all cases. The explanation as to why very little attitudinal change has occurred regarding abortion is provided by this data quite clearly: this is far more complex and deeply-rooted than simple partisan politics.

This suggests that while conversation and debate surrounding abortion is certainly partisan in how it manifests, it wouldn't be accurate to compare an American citizen's opposition to abortion to their adherence to political narratives like “Stop the Steal” or QAnon, as many are likely to do in the coming days. While things like QAnon can certainly take on the character of religious mania, they are, from the beginning, driven by politics rather than some deeper, even more transcendental belief structure. Those who consider themselves pro-life, despite being religious, can hardly be called universally “conservative” and, per the available data, it shouldn't be controversial to suggest that many millions of Americans truly, sincerely believe in the sanctity of life, even before birth. Andrew Sullivan, who once praised Hilary Clinton for her acknowledgment of “the genuine religious convictions of those who oppose all abortion”, recently wrote that, “[Abortion is,] to many, of literal life and death, and of the ultimately unknowable question of when a human being’s life begins. For many, a wrong answer to this question can result in mass killing. It’s also an issue that affects women far more than men — and the right to one’s own body is about as basic as you can get.” In other words, this is a truly, deeply-held belief and, as Sullivan noted in this same essay, not the same as something like same-sex marriage, which doesn't carry at least the implication of a life-or-death choice.

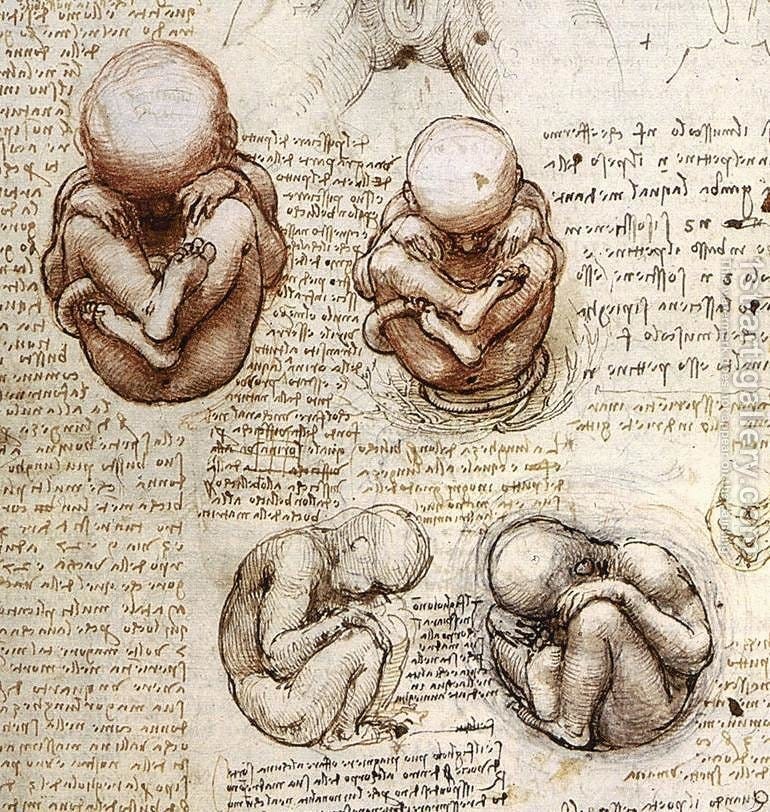

This also begs the question of whether or not this sincere spiritual conviction is borne from something deeper than religious dogma. While no one can see a baby growing within a woman (apart from the bump), humans have been shown to have a “parental instinct” region within our brains, something that likely only grows more sensitive when one has a child of their own. Protective instincts are well-studied, with NYU psychologist Lee Salk observing in the 1960s that 75-80 percent of mothers held their infants with their heads to the left, even suggesting that there was a psychobiological explanation for the phrase “close to a mother's heart.” To put an even broader point on it, pandemics and epidemics that disproportionately affect and kill children tend to produce a higher likelihood of violent scapegoating, according to a historical survey conducted by Elvesier in 2021, suggesting that the suffering of children has a broad effect on populations. In other words, there at least appears to be some sort of instinct at play when it comes to protecting the welfare of children. None of this is to say that a fetus is literally the same as an infant that has been delivered to term, but rather, to suggest that there's perhaps a much deeper reason for so many people's aversion to anything that they perceive as harming an innocent baby. The religious conviction is merely the super-structure holding up this base instinct, in other words.

This is all, of course, speculation. We don't know why so many millions of Americans oppose abortion on such deeply-felt moral grounds; we just know that they do. It speaks to just how profoundly intractable the argument is likely to become in the coming years, especially with another sizable percentage of the population (of which this author is a part, it should be said) who believes that the right to bodily agency should trump religious sensitivities. But those of us in this group would all do well not to assume that this is or possibly ever will be a settled social issue. Compromises exist, as we've seen with the crafting of legislation that, while considered toxic to some, is considered preferable to others. We have yet to see an outright state-wide ban on abortion—and that will be made all the more likely if (or once) this decision comes to pass—and we know full well that a large number of states will keep the practice in place. While it may seem obvious to many that late term abortions will be contentious, it needs to become more obvious that the topic of any abortions will always be contentious. This issue is likely never going away.

We know that there are many people on both sides of this debate who would be willing to make the necessary compromises until we can either craft better, sturdier legislation protecting the right to bodily autonomy or at least for the indefinite future. There are many who say that there shouldn't have to be a conversation about abortion, and they are free to believe that, but there are just as many people who believe the same thing, just with a different conclusion. One must work with what they have and when both sides are as convinced as they are on this issue, there are only two options: rational compromise, or outright war.