Woke Racism. A Review.

A new angry masterpiece

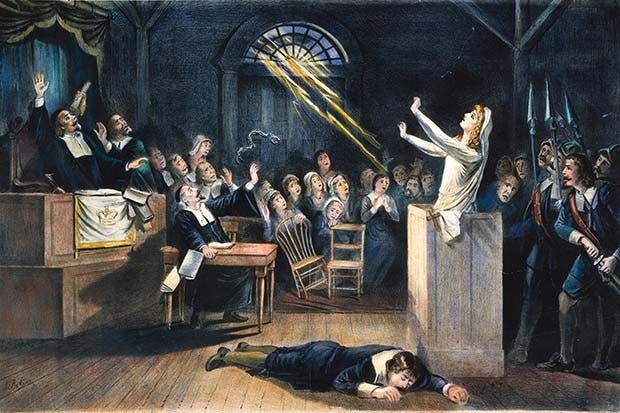

In February of 1692, the quiet New England town of Salem began to experience something that would come to define American history, nearly a century before the United States even came into existence. It would define American history, not just for its profound-if-relative strangeness, but also for just how truly normal its underlying impulses would become, if they weren’t already. Of course, this is in reference to the event that would come to be known as the Salem Witch Trials, which would last into the spring of 1693 and, had it not been for some economic boosts created by some very unlikely sources, likely would have faded into obscurity, not too dissimilar from the town clinging to dear life on Crockett Island in Netflix’s recent and brilliant Midnight Mass series.

During the witch trials, at least 25 accused witches were humiliated by strip searches, tortured during questioning, and eventually strung up for being insufficiently contrite for their supposed crimes. Many times the last words out of an accused woman’s mouth were, “I am not a wit—” cut short by the wind propelling from her throat as the noose pressed in, strangling her in slow motion for up to 20 minutes. Families turned on one another. Friends sold out friends, neighbors sold out neighbors. It became increasingly clear, especially to onlookers, that what was going on was wrong, and yet nothing was said. Not even after the famed “pressing” of Giles Corey, the 81-year-old curmudgeon whose last words were supposedly a curse upon the town of Salem (though one without any awareness of social psychology could be forgiven for believing he might have placed a hex of social hysteria on America even before its founding). It was only after the wife of the governor was accused by the increasingly unhinged (or power-hungry) sheriff of Salem and his henchmen that the trials were stopped. But by then the damage had been done.

…

In June of 2020, businesses scattered across the south side of the midwestern city of Minneapolis—my hometown as it happens—were set ablaze, looted, and pillaged in other various ways. Some acts of violence were reported, with some deaths and many injuries resulting. This was in the midst of the third month of national lockdowns brought upon the United States thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic, with no end—namely no vaccine, but also no end to lockdowns, no end to closures, no end to uncertain fear—in clear sight, and nothing but rage at the machine that was not only seemingly making things worse by basically doing nothing, but was, per the analysis that followed the callous killing of George Floyd, actively seeking to hunt down and massacre black Americans in staggering numbers never seen before.

There were no lynchings, no impromptu sentencing hearings, no kangaroo courts of any real meaning; much has been made of the cringe lawlessness of CHAZ in Seattle, much has been made of the non-stop chaos that gripped parts of Portland for months on end, and much has been made of the crime-ridden homeless encampments that sprout up across the country. These things were all connected, but Minneapolis was the epicenter of it all, the place where not only the match struck the fuse, but also the blueprint for how one of a very new and yet seemingly very familiar supposedly ideological persuasion would respond to any of the horror and disgust experienced by anyone living outside the conflagrations. While many would call criticism of the Minneapolis populace’s reaction to the riots anything from a response to “overblown” reporting at the least, you would be hard pressed not to find anything ranging from utter outrage and disbelief at your dissent to even snarling contempt, whether online or IRL from those who celebrated and even participated in the demonstrations, especially, curiously, if they hadn’t taken part in the rioting specifically.

Something was very wrong with this picture to many of us who watched. There were no accusations of witchcraft to point at and seemingly no clergy to identify…and yet it all felt eerily similar. We just didn’t have a sufficient word to describe it.

A New Faith

To anyone who read Christopher Hitchens’ own antitheistic polemic God is not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything (and with whom it resonated of course), the alarm at the obvious fundamentalism at work in summer of 2020 was almost automatic. It has indeed been difficult to put into words why—and simply calling it “the woke cult” won't do. I myself observed that it seemed part of a trend of religious “awakening” faced by Americans at various points throughout our history, but in retrospect even that seemed insufficient in explaining just how ominous and even nefarious much of this “racial reckoning” had come to feel; merely pointing out the entrance of a new denomination of Christian tradition or even a new religion itself wasn’t and isn’t sufficient to explain the unease felt by many except perhaps the most antitheistic of us. Enter John McWhorter’s Woke Racism: How a New Religion Has Betrayed Black America.

McWhorter has long been a critic from the left of this newest incarnation of antiracism in the early 21st century. There are many who would likely dispute this characterization, either out of ideological pedantry or simply because left of center is insufficiently progressive. Between his regular collaboration with his co-host Glenn Loury on Bloggingheads.tv and his Substack (that recently turned into a regular gig at the New York Times), his critiques of the excesses and increasing irrationality of the American antiracist movement stretch back over half a decade. In fact, McWhorter was likely the first high profile writer to define antiracism as “our flawed new religion” back in July of 2015. McWhorter has continued to hammer this thesis home, increasingly in rigor and persistence after the death of George Floyd and its attendant rise in riotous outbursts, and the result has become a finely-tuned tract where he not only lays out exactly how and why antiracism—which he calls “Electism” and/or the beliefs and actions of “the Elect”—has indeed become America’s new religion, how it ultimately hurts black Americans more than it helps them, and perhaps most importantly, what the rest of us—namely those on the fence on the issue—can do about it.

Who Are These People, Anyway?

The first three chapters of McWhorter's slim volume lay out just exactly who he means by “the Elect”, how what they believe and what they do can only be explained by religious conviction, and why this new faith is so appealing to seemingly so many people (or perhaps at least why so many people are seemingly terrified to resist its influence). These chapters are more enjoyable for their witty prose to fans of McWhorter's work, with much of it being well-tread territory for anyone who watches, listens to, or reads him. However, without these chapters, the pure strength and rage felt in the latter chapters would likely seem quite impotent. In the first few pages of the book, McWhorter asks the simple question: what kind of people? Namely, what kind of people would do these things? (“These things” being the firing of figures like Alison Roman from the New York Times for the crime of critiquing two public figures of Asian descent while being white, the rapid sacking of Leslie Neal-Boylan from the University of Massachusetts at Lowell for suggesting that everyone’s life matters, and the expulsion of progressive data analyst David Shor from the consulting firm where he worked for sharing a study that suggested violent protest was detrimental to social movement efficacy).

To explain the Elect, or those who follow the tenets of what McWhorter calls Third Wave Antiracism, he lays out ten contradictory statements that likely sound all too familiar, at least to those who run in activist circles or who work in academia; things like silence about racism being violence paired with the need to elevate the voices of the oppressed over your own, or things like dating only white people signifying racism paired with dating someone of a different race signifying your guilt of exotifying an “other”, or things like the importance of multiculturalism paired with the profound problems that come from cultural appropriation. All of these contradictions, McWhorter maintains, aren’t signals of stupidity or confusion: the contradictions are the point. And as many-a-theologian will remind us, the contradictions of a religion are indeed the point because without those contradictions, faith wouldn’t serve much of a purpose. So too does McWhorter highlight this frequently throughout the book, and always to great effect.

And of course there must indeed be a term to describe these people who truly embrace the contradictions without question and see true wisdom in the nonsense. Pulling from the writings of Joseph Buttom, McWhorter calls these people “the Elect,” writing:

“They do think of themselves as bearers of a wisdom, granted them for any number of reasons—empathic leaning, life experience, maybe even intelligence. But they see themselves as having been chosen, as it were, by one or some of these factors, as understanding something most do not. ‘The Elect’ is also good at implying a certain smugness, which, sadly, is an accurate description. … [But] they are not smug. They are evangelists. They are normal—as are all religious people.”

And indeed McWhorter asks his rhetorical question, “what kind of people do these things?” and very plainly and immediately answers: religious fundamentalists. This charge forms the backbone of the entire book, with McWhorter going on to very plainly say that this ideology is not “like” a religion, but that indeed it is a religion. They “have superstition” (the way they frame racism in almost spiritual terms), they “have a clergy” (the unintentional Ta-Nahesi Coates, and very intentional Robin DiAngelo and Ibram Kendi), they “have original sin” (white privilege), they “are apocalyptic” (always pointing to that Aquinan city on a hill when “America ‘owns up to’ or ‘comes to terms with’ racism and finally fixes it”), they “ban the heretic” (most instances of racial issue-related “cancellations”, which typically amount to blaspheming), and they “supplant older religions” (transforming many American churches’ and clergies’ vocabulary regarding social justice, from the Unitarian Universalist Association to New York City’s Church of St. Xavier). McWhorter leaves this unsaid, but one can also see, just as the Christian proselytizers of days past and present, that the Elect as being bearers sentimentality, what James Baldwin once called “the ostentatious parading of excessive and spurious emotion” and “the signal of secret and violent inhumanity, the mask of cruelty.”

Much of this characterization fundamentally helps explain the pushback this type of thinking has received—particularly from those who count themselves as atheists or find religion distasteful. Of course much has been and will continue to be said that any discomfort with this rhetorical sea change—this “racial reckoning”—is the result of “white anxiety” or, dare it be said, “white fragility,” but this doesn't quite wash either, per McWhorter's analysis or simply per common sense and using our eyes and ears. There is more diversity in the “anti-woke” pushback than within the woke crowd to begin with, particularly when one factors class into the equation. But in the end, the “racial reckoning” gripping the United States, seems to mostly manifest in claims of “doing the work” (typically meaning mental work) or “sitting with discomfort or defensiveness” as being ends in and of themselves. The thinking may go that once “the work” is done and “the discomfort or defensiveness” is sat with, attitudes will change, and thus society; one might call it “trickle-down social justice” (pardon me while I vomit). But one may wonder: how does this help people of color now? Indeed, as McWhorter asks, how does white penance for past sins committed by whites really help blacks achieve and succeed? It doesn’t take long to see that much of what has come to be seen as “white allyship” amounts to little more than performance, and claims of “doing the work” or “sitting with the discomfort” look little different from saying your nightly prayers. It’s also worth pointing out, as McWhorter does, that this “work” is never done, as is often the case with religion, because as any openly religious person will tell you, the work of the spirit is eternal. It's that work—that process—that provides meaning and, hopefully, guidance. But when married to such a material, superficial concern as that of race, the “work” takes on a much more troubling dimension. As McWhorter writes:

“To these people, actual progress on race is not something to celebrate, but to talk around. This is because, with progress, the Elect lose their sense of purpose. Note: What they are after is not money or power, but sheer purpose, in the basic sense of feeling like you matter and that your life has a meaningful agenda.”

What Animates These People?

Woke Racism truly starts picking up speed when McWhorter starts exploring the more difficult question of what makes this new religion so appealing, primarily to whites and blacks, the two demographics upon which the faith hinges. For whites, McWhorter notes that the Elect are a logical conclusion to what Richard Rorty referred to the shift of a reformist left to a cultural left that occurred after the 1960s. To be Elect while white is to engage in justification of cultural pessimism: America is a rotten place and things have never been worse, and the evidence is right in front of us as these countless black men are murdered with impunity by our law enforcement. It’s to conform to a particular strain of thought that gives one a sense of relief and belonging, as observed by Csezlaw Milosz. It’s to simply feel good, engaging in what Pascal Bruckner referred to as “Western masochism”, or a form of what Goran Adamson more recently called “masochistic nationalism”: the pleasure of being seen as morally corrupt (with of course salvation to follow from this admission of “responsibility”). And finally, perhaps most tellingly, to be Elect while white is easy. True, it's given an air of sophistication, with Robin DiAngelo's insistence on soul searching, and even a supposed air of elegance, with Ibram Kendi’s Manichean dualism of everything being “either racist or antiracist.” But this sophisticated elegance is all in appearance—as McWhorter likes to intone, it’s kabuki. As he writes, “If Elect philosophy were really about changing the world, its parishioners would be ever chomping at the bit to get out and do the changing, like Jane Addams and Dr. King.”

Woke Racism is in some ways at its most challenging—intellectually and emotionally—when McWhorter addresses the black members of the Elect and, perhaps more importantly, what drives and motivates them and steers them toward this new religion. This is challenging especially for a white reader more sensitive to racial grievances, despite his own critical tendencies, because, to be blunt, McWhorter’s analysis is not for a white person to make. One could argue it’s not for anyone to make, as we are all individuals with our own motivations never truly known to no one but ourselves, but putting that aside for the philosophers, McWhorter offers some poignant critiques of what may motivate a black American to become Elect. Common sense as it is to posit that pure self-interest motivates the black Elect, that simply won't do, per McWhorter's outlook. True, it's hard to imagine anyone saying “no” to cultural anointment or perhaps even sainthood that is provided at little to no material cost, but McWhorter makes compelling enough arguments showing how this essentially negates the possibility of self-respect and, more to the point, only allows for blacks to have a sense of purpose and even identity through the lens of victimhood at the hands of white oppressors, rather than masters of their own destiny. McWhorter has made it very clear that he’s not referring to the black Elect as being too dim to realize that they’re being condescended to but rather, that they are being given a false sense of purpose that only serves to keep them downtrodden.

Using the famous 1950s experiment demonstrating black children preferring white dolls as his example, McWhorter’s challenging assertion is that black Americans, in their 300 years of being treated like animals, had been cursed with “a damaged racial self-image,” producing a long-running inferiority complex (which can only be amplified by less-than-ideal economic and family circumstances, as studies have shown) leading to an incentive for many black people to begin identifying themselves as “the noble victim.” As McWhorter explains:

“If you lack an internally generated sense of what makes you legitimate, what makes you special, then a handy substitute is the idea of yourself as a survivor. If you are insecure, a handy strategy is to point out the bad thing someone else is doing—we all remember that type from our school days—and especially if the idea is that they are doing it to you.”

This isn’t to say McWhorter’s observation is only meant to apply to black people; it applies to everyone. He’s also not claiming that all black people experience this—millions don't. But with black Americans' peculiar place (to put it mildly) in the annals of American history, identifying as a “survivor” or “noble victim” takes on a new meaning and disconnects very quickly started to appear after the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the Fair Housing Act of 1968. These disconnects were what, as McWhorter notes, “perplexed” and even “put off” a lot of older generations of black Americans who had experienced true oppression under Jim Crow and watched as their children entering and thriving in academia and the intelligentsia begin to claim that things in 1970 (never mind 2021) were objectively as bad as they were in 1940. Legal progress had been made but it wasn’t enough to assuage any void in one’s self-esteem, something that had long been imposed onto black Americans’ psyches for generation after generation. McWhorter traces this strain of thought within the black American intelligentsia not back to the beginning of critical race theory in the early 1990s, but rather to the late 1960s when the new generation of black intellectuals began to pursue something supposedly deeper than “mere” civil rights. Pointing at the black psychiatrist Price Cobbs’ 1970 struggle session in which he claimed a white woman was lying when she said she saw people as individuals, McWhorter attempts to demonstrate that this concern with how white people (or really all people) perceived black people, even in the privacy of their own minds, began to matter more than any legislative or economic or otherwise material gains, which arguably helped more than anything else in transforming antiracism into a religion (what else is psychological validation if not a matter of the soul?). Indeed, it’s this insecurity that explains the infuriated pushback that occurs when someone disagrees with a particularly fervant member of the black Elect. As McWhorter explains, “The fury is that of someone who feels one’s entire sense of purpose and legitimacy as a human being is under interrogation and threat.”

What ultimately makes this so challenging and perhaps even problematic is that McWhorter can be seen as telling black Americans who may be experiencing this social insecurity how to feel about it, or rather, how not to feel about it, rather than letting them process their feelings in whatever way works best for them. However, this challenge is necessary to understand McWhorter’s self-described true purpose in writing Woke Racism: that this new religion hurts, above all else, black people. While it certainly has had its share of casualties in all identity groups—and McWhorter doesn’t dispute this—it’s the religion’s claim that it is all about helping black people that makes it such a bitter pill to swallow. McWhorter lays out what he believes is truly required to be among the Elect:

“You are to turn a blind eye to black kids getting jumped by other ones at school. You are to turn a blind eye to black undergraduates cast into schools where they are in over their heads, and into law schools incapable of adjusting to their level of preparation in a way that will allow them to pass the bar exam. ... You are to turn a blind eye to the folly in the idea of black ‘identity’ as all about what whites think rather than what black people themselves think. You are to turn a blind eye to lapses in black intellectuals’ work because black people lack white privilege. You are to turn a blind eye to the fact that social history is complex, and instead pretend that those who tell you that all racial discrepancies are a result of racism are evidencing brilliance.”

McWhorter lays out several examples of how these statements and others manifest in the harm of black Americans, from the efforts to lower suspensions of black boys in school resulting in more assaults between black boys, to the condescension inherent in changing admissions standards to elite colleges, as well as not holding black intellectuals’ faulty work (see also: the 1619 Project) to the same rigorous standards as experienced by other racial demographics, to ultimately defining yourself based on how you think others see you. With this last example, McWhorter provides his most psychologically compelling reason to be suspicious of this new religion on the grounds of it hurting the minds of black people:

“Under the Elect, blackness becomes what you aren’t—i.e., fully seen by whites—as opposed to what you are. It is what someone does to you, rather than what you like to do. And all of this is thought of as advanced, rather than backward thought. All ‘because racism.’ Racism uber alles, but the problem is that Elect philosophy teaches black people to live obsessed with just how someone maybe doesn’t quite fully like them, and then die unappeased.”

In putting a fine point on this, McWhorter then asks the fundamental question in response to this: “This is the meaning of life? This is the grand answer that philosophy has been seeking for millennia?”

What to Do About This and About Them?

Because black Americans are human, they are just as capable of success or failure as anyone else in a vacuum: McWhorter stresses this perhaps more than any other sentiment throughout his book. But more importantly, he doesn't simply lay out all of these criticisms—warts and all—and then grumpily mutter something about pulling your pants up and getting a job. On the contrary, when we arrive at Woke Racism's final two chapters that offer pragmatic, if sweeping (and perhaps overgeneralized) solutions, we see that McWhorter is by no means making a “bootstraps” argument. He lays out three main planks: ending the war on drugs (which largely puts an end to the school-to-prison pipeline and severely reduces the unhealthy interactions between police and black civilians), teaching reading through phonics (since, according to McWhorter, a celebrated linguist it should be remembered, it's more effective at teaching reading and thus improving scholastic skills with all students, especially under-performing black ones), and finally, doing away with the idea that college is the end-all, be-all solution to prosperity and happiness and improved access to vocational education (which effectively lowers the pressure and thus incentive for elite institutions to condescend and treat black applicants like simpletons and provides an increasing number of valuable vocational career paths that don't require four years and massive debt).

These are the long-term, legislative projects (excepting the last one, which is more of a sociocultural standard) with no real evidence to support them beyond the “common sense” interpretations laid out by McWhorter, but that was never the point of this book. These planks are starting points, nothing more, and ultimately, don't have any apparent downsides and likely would see wide, multi-partisan support throughout the United States. This is why McWhorter doesn't dwell on them for very long and—frustrating as that can be—focuses his last chapter instead on one of the fundamental questions he asked from the outset: what do we do about these Elect now? And his answer is quite simple: we learn to live with them and “work around” them.

All of this isn't to say McWhorter would have these people cast out of society like lepers. This religion is indeed here to stay and its adherents may be our closest friends and family members. We must learn to live with these people just as we have learned to live with Pentecostals, Hasidic Jews, or conservative Muslims. As McWhorter has taken to saying, these people have always had a seat at the table, but now they're standing over us; it's time for them to sit back down with the rest of us. And what that requires, ultimately, is for the rest of us to treat them like the religious ideologues they are and simply say “no, I don’t agree with you.” Like Christopher Hitchens was prone to saying, they can play with their toys however much they want, but they won't foist those toys upon me. The goal is to separate church and state as it were; not to debate them, for they can't be reached (just as a fundamentalist Christian can't be reached and convinced that Jesus doesn't love them), but to push back. And as John McWhorter would have it, the pushback must be reserved for when, just as we have pushed back against fundamentalist Christians attempting to rob women's agency over their own bodies or the rights of gays and lesbians to marry, the Elect attempt to wield their religion as a policy club. And all that requires, as McWhorter concludes his book, is for us to remember that we are not moral perverts for disagreeing with them, for being skeptical of this new wave of antiracism, and, most importantly, to stand up.

…

Salem was dead. It was a husk of a town, riddled with trauma, like so many places that have endured mass violence and uncertainty, but also, perhaps more importantly, economically. The economy of Salem crashed and burned in the years that followed the Witch Trials, with many outsiders looking at what happened with horror and deciding they wanted nothing to do with a town that had literally existed for a year in the throes of madness that appeared to have affected everyone. Eventually, people in the quiet coastal town had to turn to privateering to make ends meet, often smuggling large amounts of rum to various locations around the Atlantic and contributing to the so-called “Golden Age of Piracy.” Eventually—and by eventually, I mean it: October 31st, 2001—the accused and punished were granted pardon and deemed innocent of their supposed crimes. A nice gesture, yes, but one that came over 300 years too late.

…

Woke Racism: How a New Religion Has Betrayed Black America is available for $15.99 on Kindle and $18.01 in hardcover over on Amazon.

It seems to me that Mr McWhorter and I must be twins separated at birth, or some such thing. I have long held the belief that identity groups of all stripes have one overwhelming Achilles heel, and that is their complete lack of a plan, including what ultimate success would look like. When is it tools-down time, let's all congratulate each other for the great progress, and let's disband and enjoy our hard-earned status as societal equals? Apparently that time is never, since it is seemingly impossible to relinquish the one thing you erroneously believe makes you special and important: your victimhood.

Now, having said that......I've never been made a victim, or felt like a victim either personally, or as part of a larger group. In an attempt at empathy (I believe true empathy is literally impossible since you cannot truly put yourself in anyone elses shoes) I try to understand the fear that might drive such vehement adherence to the role of the oppressed. Many cultures and "races" have been brutally, and also subtly oppressed for many, many years, and have then (often grudgingly) been given incremental improvements through legislation and general shifts in social attitudes. But ask any abuse victim, such as a female victim of domestic abuse, and they will tell you that trusting someone who swears they've changed, and they're really sorry isn't an easy thing to do. The original aggressor/oppressor is still present, still bigger and stronger and their motivations and future intentions are somewhat unknown. Any time that it feels like doing so the original aggressor can simply undo all their promises, and the original victim takes the fallout. Through this lens it becomes easier (speaking for myself) to see how these things may take far longer to fully shake out than we might find comfortable. For example, ask me if I think the Mexica/Spanish horror show has fully shaken out. I do not. As much as I dislike the rhetoric of the race hustlers I do try to keep in mind that their mileage has varied (had to, sorry) and maybe they have a particularly gruesome family history with parents and grandparents telling stories of trauma. Maybe the trust that their neighbours and country won't turn on them just will not be gained in their lifetimes. Or maybe they're just doing it for limelight and book sales or the sheer joy of shouting down Jordan Peterson. It is very cringey to listen to, and I disagree with most of what they say, but I still feel that it might just need more time. That's a difficult concept, because as I said earlier, there is no specific end goal or finish line where everyone can agree to stop fighting for what most common sense folks think has already been achieved. It is especially difficult to grant more time when you see your city getting rolled up for no good reason.

Solutions, you ask? Well, my ideas are pretty pedestrian and can be found in almost any , but here goes: check your biases when dealing with an identity group, try to make sure you're being the fair person you believe yourself to be, and stay the course. No need to self-flagelate, confess to things you didn't do, apologize for things you never even heard of. Just be a decent person and wait it out, because decency and middle-of-the-road normalcy should always prevail.