Hurricanes Tethered, Awaiting Their Hour

On the Charlie Kirk assassination and political violence

In reading The Revolution Betrayed by Leon Trostsky this week as part of my graduate studies on European revolutions of the 20th century, I was stopped dead in my tracks when I read the following line in its concluding pages:

Individual terror is a weapon of impatient or despairing individuals, belonging most frequently to the younger generation. But, as was the case in Tsarist times, political murders are unmistakable symptoms of a stormy atmosphere, and foretell the beginning of an open political crisis.

Our professor obviously had no inkling of what was going to happen on September 10th, 2025. But he understood, as he made clear as we discussed the role of workers in the Russian Revolution, that the United States has not seen the levels of escalating political violence that have characterized much of the 2020s in my entire lifetime.

Personally speaking, I haven’t really been able to properly articulate why the story of Charlie Kirk’s assassination, bothers me so much compared to other examples of the escalating political violence and explicit approval of it that I’ve been seeing ramp up for years now; from the ugly riots of summer 2020 all the way to the killing of United HealthCare CEO Brian Thompson at the end of 2024 (to say nothing of other horrifying recent events, like the antisemitic murder of Sarah Milgrim and Yaron Lischinsky as they left the Capital Jewish Museum), political violence has already been relatively “normal” up until this particular event. But talking to the most amazing woman in my life, my partner Molly, helped crystallize it for me.

We were walking our dogs and I was recapping the story for her and answering her questions about why this has hit so hard for so many people, both as something to cheer and something to mourn. It eventually got to my resentment of the people cheering on this man’s murder and the bloodlust being experienced by those most hurt by it all. I off-handedly mentioned that it just bothered me because it was so clearly motivated by weakness, hypocrisy, and performative cruelty on seemingly everyone’s part, with the only logical conclusion being more violence. She then very matter-of-factly said, “well, you’re also in Charlie Kirk’s business.”

By that she didn’t mean conservative activism or public debates with college students; she meant punditry. My focus is obviously history, but I also do follow and comment on politics and, if we are honest, history inevitably crosses streams with politics. Someone who discusses these things honestly and doesn’t consider themselves a journalist is going to come off as a pundit; they essentially are a pundit whether they like it or not. In other words, to quote journalist Jesse Singal on a recent episode of Blocked and Reported, slinging ideas for a living.

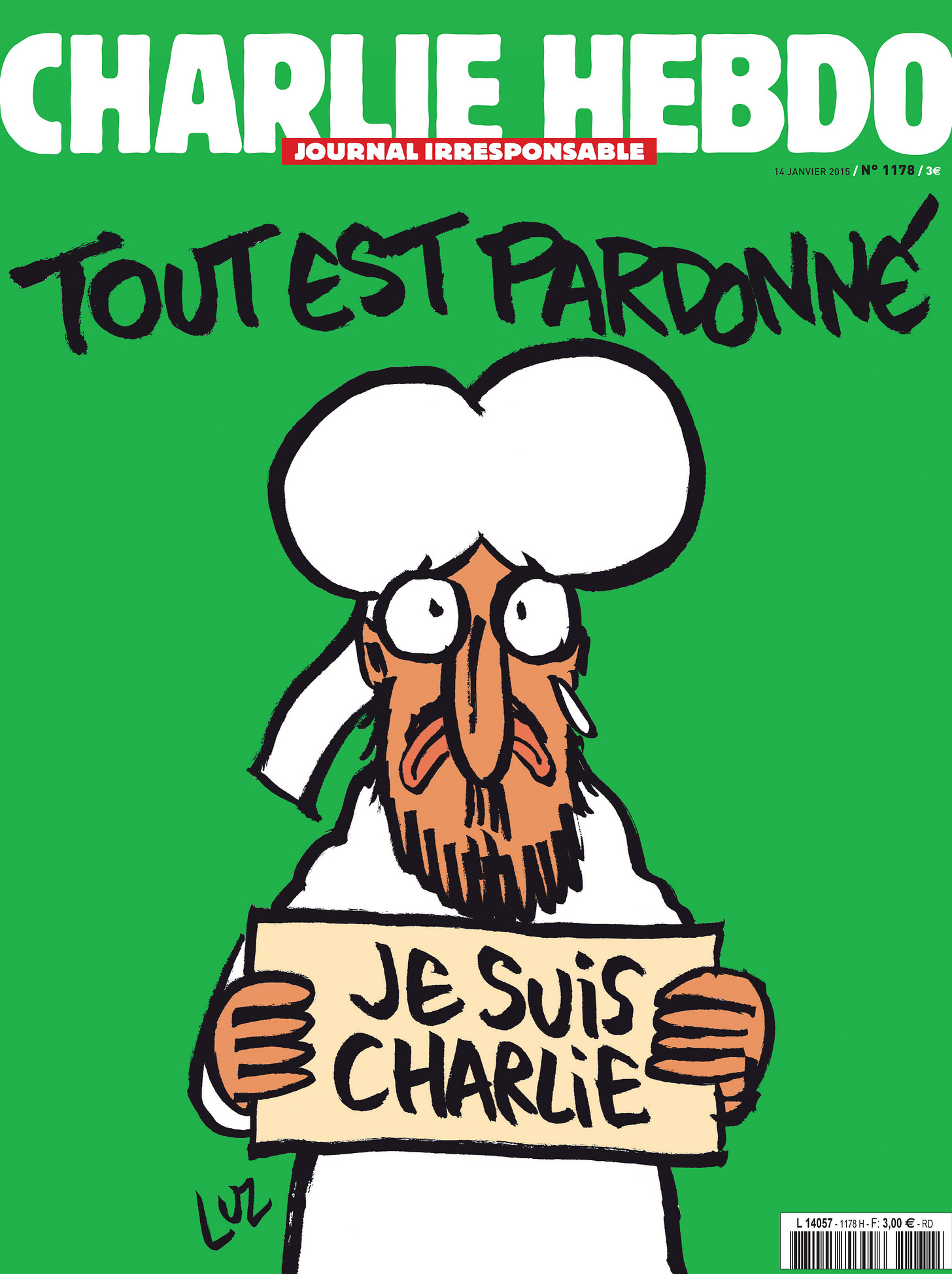

This is why, with very few exceptions, I have yet to hear any of my podcasting and writing comrades and people whose work I enjoy—all of whom with wildly different political views across the spectrum—have had the same exact reaction as me: seeing this as a broad threat not particularly coming from any “side.” Even most those in the space I occupy who are ready to pin the blame on transgender antifa Marxists or Nick Fuentes’ Groyper cult (despite growing evidence at least against the latter), all recognize the broader threat of political violence itself as being the true, root problem at hand. The last time a lot of people, including me, felt this way was after the massacre at the Charlie Hebdo offices by Islamist thugs. That’s why, in my opinion, it’s not fair or accurate to say that these reactions are driven by fear of repercussions. The desire to simply reach for low-hanging fruit and try to seem edgy is not as strong as a revulsion at viewpoints, however controversial, being met with actual destructive violence, at least to those of us who, to use Singal’s term again, sling ideas for a living.

This is not to compare myself or anyone I know to Charlie Kirk quantitatively; given his massive success and cultural and political influence, that would not be possible. This is to say, however, why this killing likely feels significantly different to so many of us out there; why it’s different to me. I’ve come to believe, sadly, that the number of us who actually want to express ourselves without fear of violence being used as a reaction is actually not really that high, but that’s because, frankly, we are weird people that believe this stuff matters. So it’s therefore different for me when a pundit—no matter what kind of things he is espousing—is shot for what he says.

Because make no mistake: that is what happened. Charlie Kirk was shot through the throat and killed not because he was a bad person, or because he was a bigot, or because he hurt anything more substantive than other people’s feelings; Charlie Kirk was shot through the throat and killed because he said things. Maybe those things he said were awful, according to you, but he was still shot for what he said. Not what he did.

Maybe this last way of explaining it, via basic moral philosophy, will make some people understand this perspective better: if Donald Trump had been killed last year, obviously the consequences would have been devastating and by general moral metrics it would be a tragedy, but one could, in theory, make a moral argument for that outcome the same way people make the classic “using a time machine to go to 19th century Austria to find baby Hitler” arguments. A president makes choices that literally kill people, after all.1 But, unless you literally believe words and beliefs are violent acts themselves, a pundits like Charlie Kirk have never caused anything with what they do. Common sense might tell you speech causes violence but 1.) it has been proven over and over again via psychological research that there is no causal connection, and 2.) even if there was, ask yourself: do you really want to go down that road to its logical conclusion? Longtime readers know this is the thing that concerns me most when it comes to the protection of speech. If you’ll pardon a paraphrased cliche, pundits don’t kill people; assassins—assassins that are too insecure to live in a world where people are free to believe and say what they want—do.

With all of that said, like a lot of people in this business I was describing, I see the assassination of Charlie Kirk as part of something far worse facing the United States; something that many of us have been clamoring about for years now. That is, the escalation of political violence. In an effort to help get across why this is as bad as it is, I’m planning to have a conversation with some fellow podcasters this coming week who know a thing or two about escalated political violence, thanks to their upbringings in very different cultures from our own. In the meantime, however, I want to reshare a written adaptation of something I discussed in an earlier episode of History Impossible, from the first part of the “Balkan Inferno” trilogy, “The Yugoslav Vortex.” In this story, you will see first hand what Trotsky spoke of when he warned of “open political crisis.” I can only hope that it will get through to the people clamoring for a new civil war or who think a political assassination of a “bad person” is no big deal, and in fact worth celebrating. Because this story is what it looks like when a country is truly polarized; this is what it looks like when political norms have truly broken down.

…

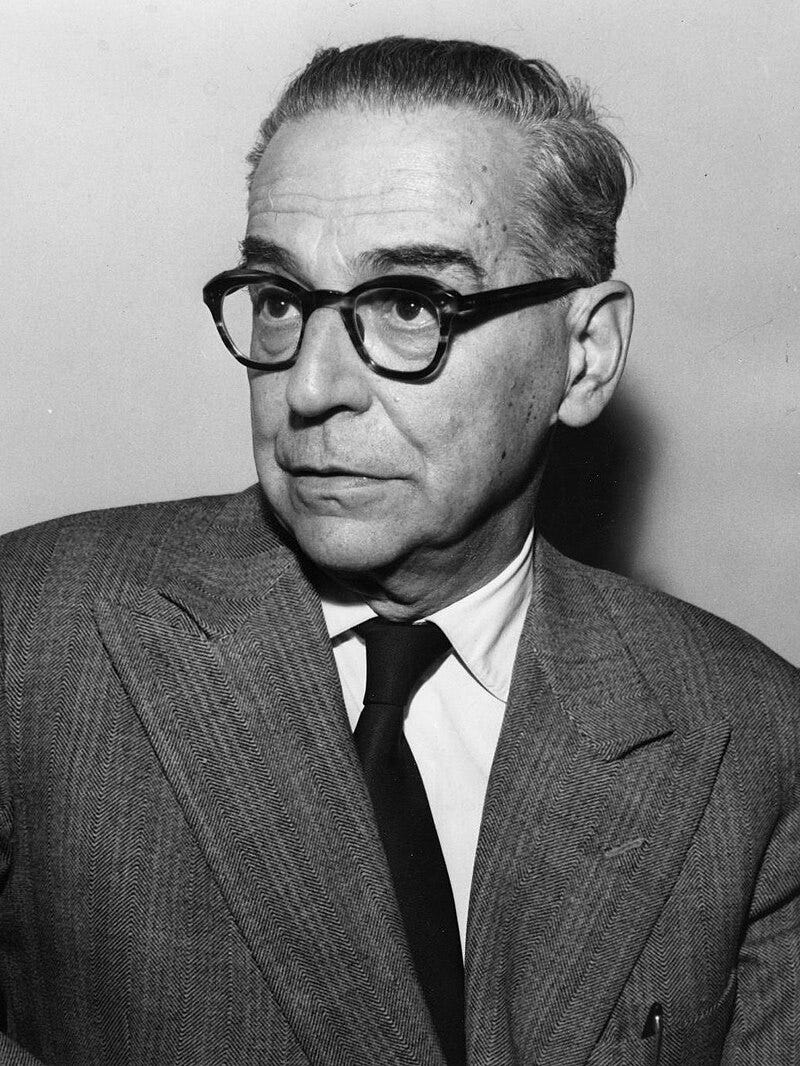

In his short story “A Letter from 1920,” Yugoslav writer (and eventual Nobel Prize laureate) Ivo Andrić would write the following of his native homeland of Bosnia, one of the many nations incorporated into Yugoslavia:

[B]y strange contrast, which in fact isn't so strange, and could perhaps be easily explained by careful analysis, it can also be said that there are a few countries with such firm belief, elevated strength of character, so much tenderness and loving passion, such depth of feeling, of loyalty and unshakable devotion, or with such a thirst for justice. But in secret depths underneath all this hide burning hatreds, entire hurricanes of tethered and compressed hatreds maturing and awaiting their hour.

When Andrić wrote these words, the Vidovdan Constitution had not even been written yet, much less passed; the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes—later to be known as the Kingdom of Yugoslavia—was in the midst of its painful birthing process. In less than a decade, the democracy at the core of this new Kingdom would be completely gone.

On the night of June 20th, 1928, the floor of the Yugoslav parliament was soaked with the blood of three of its Croatian members, representatives from the Croatian People's Party, including its leader, Stjepan Radić. The three, including Radić's own nephew Pavle, had been shot by a parliamentary member of the Serbian People's Radical Party (or the Radicals), a one Puniša Račić, after the debates rocking the parliamentary floor had grown increasingly filled with shouted accusations and violent threats. Račić, a longtime supporter of the Radical Serbian cause and something of a son to the Radicals' leader and Prime Minister of Yugoslavia, Nikola Pašić, who had long-encouraged the young Račić in his political ambitions until his—that is, Pašić's—death in 1926. There is evidence that much of this was premeditated since, earlier that day on June 20th, Račić had met with the King of Yugoslavia, Aleksandar, and, as historian Misha Glenny puts it, “strode purposefully out of [the King's] chambers.” As Glenny also notes, no one knows what had been discussed between Račić and the King (seeing as it was a private audience), but what is known is that Račić “left the palace an angry man with a revolver in his pocket.” Only a few hours later, he would be arrested and three of his political (and ethnic) opponents—including a beloved Croat leader—would be dead, with Montenegrin representative calling the event “one of the worst nights of my life.”

It began when Puniša Račić and another member of the Radicals, Toma Popović, had shouted in the middle of a parliamentary session, “Heads are going to roll here and until someone kills Stjepan Radić there can be no peace!” With their leader's life being essentially directly threatened (both here and previously in the Serbian nationalist press), this then prompted insults to be shouted at one of the Serbian politicians by a Croatian People's Party deputy named Ivan Pernar, who shouted, “Oh yes, what a hero! He slaughtered defenseless people in cold blood. You're real Robin Hoods, you are! You've slaughtered people, you've eaten people and you know it. And after such heroic deeds, you proclaim yourselves Dukes!” And if accusing a member of parliament of cannibalism wasn't enough, Pernar continued his harangue at a different Serb politician named Pechanac, shouting, “Oh we know about Comrade Kosta Pećanac! He massacred 200 Muslim children and pensioners! He slaughtered them like sheep. You killed them like chickens […] Is it not true that Voyvoda [Duke] Pećanac killed 200 Muslims in 1921? Just tell us it's not true!” Now, I couldn't find any evidence of either of these claims, though it's known that Kosta Pećanac did play a role in suppressing Muslim votes under the orders of Serb Radical leader Nikola Pašić in 1921. Regardless, as Misha Glenny explains, “The mood in the [Parliament had] turned extremely nasty, even by its own standards.” Continuing, Glenny writes:

“When [Serbian Radical Toma] Popovich repeated his warning that he would murder Pašić, there was an uproar on the opposition benches. Insults were bawled across the floor, tables were banged and death threats hurled around with abandon. Ninko Perich, the [Serb] Radical who presided over this undignified assembly as Speaker, refused to cancel the session and instead ordered a recess of five minutes. Having spoken with Punisha Rachich in his private chamber, Perich then invited the Radical member to take the floor.”

During what was apparently a bit of a meandering speech that mostly recycled the Radical Serbian nationalist talking points typical of the day, Račić was likely set off by Ivan Pernar heckling him just as he had heckled the other Serbians earlier, with Pernar shouting that Račić , like the others, had looted Muslim houses in Macedonia, shouting “you plundered beys!” using the old Ottoman terminology. The Zagreb newspaper Novosti's correspondent who was present when this happened described what then happened:

“Račić, expecting Dr. Pernar to be called to order, turns towards the Speaker while slipping his hand into his right pocket where his revolver is hidden. At this time, the most indescribable commotion is going on. At exactly 11:25, seeing that the Speaker does not intend to enforce the satisfaction he had demanded of Dr. Pernar, Puniša Račić takes the gun from his pocket. The Justice Minister [Milorad] Vujičić, who is sitting behind the podium, grabs Račić's back. The former Minister of Religion, Obradović, seizes his right shoulder. Puniša Račić shrugs them off, throwing Vujičić against the ministerial bench while Obradović is sent flying several meters. Rude Bacinić runs to the Speaker, screaming, 'Stop this, blood is going to be spilled!' Everything happened to quickly and the whole house was so shocked that nobody was able to prevent the catastrophe.”

And catastrophe it was. Račić first fired on his (and the rest of the Serbs') main interlocutor, Ivan Pernar, striking him and another member of the Croatian Peasant Party, injuring both of them. The strangest part of this story that gets repeated in all the secondary and primary sources is what the head of the Croatian Peasant Party—Stjepan Radić, the man who had been having his life threatened in both the press and on the floor of the parliament—sat perfectly still the entire time as the room erupted into bloody chaos, seemingly in a meditative trance. And this, unfortunately, made him an easy target: after shooting his first two targets, Račić immediately turned to the 57-year-old statesman and without missing a beat, shot him in the stomach. As Radić keeled over, groaning in pain, his nephew, Pavle, rushed down the length of the hall to help him. As he neared, Račić turned and saw him, apparently smiled and said, “I've been waiting for you” and shot him through the heart.

Unlike his nephew, Radić didn't die from his gunshot wound. At least not right away. While his nephew and Djuro Basarichek—the other Croatian Peasant Party representative killed in the attack—died pretty much on the spot, Radić lingered and was even able to return to the parliamentary floor after being given a positive prognosis by his attended physician. But his health took a turn for the worse and on August 8th, 1928, he died. While new coalition had been formed and a Slovenian named Anton Korosec had been made Prime Minister—likely seen as a way to keep things “fair,” at least in ethnonational terms by sidestepping the inevitable controversy the appointment of another Serb or a Croat would bring—Radić's death all but guaranteed further breakdown of the fragile political system in the young kingdom. Croat nationalism could only grow and fester further into anti-Serb animus at this point, made even worse when, on December 1st, 1928, three students were killed by police while demonstrating by celebrating Croatian identity on the 10th anniversary of the kingdom's formation.

I often make it a point to say that nothing in history is inevitable, things had been building to this point throughout the 1920s in the young Yugoslav kingdom. Many territorial concessions had been made, angering both Croats and Slovenes who lost land that they saw as nominally theirs to outside powers—including Italy—all seemingly to the benefit of the Serbs in power, since the land granted to the Yugoslav kingdom in return for these concessions (namely territories in Albania and Macedonia) was largely dominated by ethnic Serbs, leaving the ethnic Croats and Slovenes in the conceded territory, yet again, under the thumb of an outside imperial power.

In addition to the drama caused by things like this, democracy was increasingly being seen by most Yugoslavs, especially the non-Serb nationalists among them, as a total fraud; a scam that only seemed to benefit the Serbs at every turn. And given that democracy was a very novel concept in Yugoslavia—something the centralizers who dreamed of a unified South Slav state were determined to find compromises for, which including softening the centralization in favor of a looser, “soft” federalism—it was not difficult for the nationalist types, especially in Croatia (and especially after the assassination of Radić) to become completely disillusioned with the whole project. And while the coalition tried to find concessions and compromises that would please everyone, they ended up pleasing no one, and, thus, infuriating everyone.

Both Croats and ethnic Serbs in Croatia eventually ended all cooperation with the Belgrade government and began to issue demands of the new Slovenian Prime Minister there that he could not possibly meet, leading him to resign in disgrace. Within the span of half a year, the decade-old democracy had already ceased functioning. And, in an effort to preserve his decade-old Kingdom (though likely in his mind, his two-century-long claim to it), the Serbian King Aleksandar did something that, at this point, would only confirm the disillusionment and resentment of the non-Serb nationalists living within his kingdom. On January 6th, 1929, a manifesto written by the King was distributed to all public officials to be published across the Kingdom's territories. It read, in part, as follows:

To my dear people, to all Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, the hour has come where there can and will no longer be any intermediaries between the people and the King. In the course of executing all my high duties in the execution of which I have demonstrated such great efforts and such patience, my soul has been plagued by the cry of our popular masses. [...] [T]hey have, guided by their natural common sense, long ago discerned that it is no longer possible to take the path which we have hitherto taken. Parliamentary order and our whole political life are taking on ever more negative characteristics, from which the people and the state have now derived only damages. Parliamentarism, which as a political means in the traditions of my unforgettable father, has remained my ideal as well, but began to be abused by blind political passions to such an extent that it became a hindrance for each fruitful labor in the states. Agreements, even the most normal relations between parties and people, became absolutely impossible. It is my sacred duty to employ all means to preserve state and national unity, and I have resolved to fulfill this duty without hesitation to the end. Because of that, I have decided that the Constitution of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes of the 28th of June, 1921, ceases to be valid. The national parliament elected on the 11th of September, 1927, is dissolved. All laws of the land remain enforced, as long as it is not necessary to change them by my decree. In the future, new laws will be promulgated in the same manner. In communicating to my people my decision, I order all authorities in the state to act in accordance with it, and I order every one and each one to respect and obey it.

The Yugoslav democratic experiment was officially over, and thanks to deft political maneuvering, the mobilization of loyal parts of the military, and the overall skepticism of democracy that had been infecting much of the Kingdom, he was largely unopposed in his seizure of power.

That power would only last another five years. But the violence, clearly endemic from the assassinations that had erupted in Parliament in the summer of 1928, ratcheted up almost immediately from the enraged Croat ultranationalist camp in the wake of the new Serb-led dictatorship. Historian Misha Glenny tells us what happened next as follows:

On March 23rd, 1929, at around 8 o'clock in the evening, Toni Schlegel, the Croat editor of the pro-Yugoslav [i.e. anti-nationalist] Novosti, and a personal friend of King Aleksandar, left his office in [the Croatian capital of] Zagreb's Masaryk Street. Walking past the elegant shop fronts on one of the city's most charming streets, Schlegel took a cab from the stand outside Zagreb's most poplar meeting point, the Theatre Café. Marko Hranilović, a member of the recently formed Hrvatski domobran (Croatian Home Guard), jumped into the next taxi and followed him home. When Schlegel reached his front door at Prilaz No. 86, Hranilović leaped out of the taxi and drew his revolver. Before he could fire, however, one of his co-conspirators who had been waiting at the flat gunned Schlegel down. The hit team succeeded in killing two policemen before Hranilović was finally taken into custody. His two co-conspirators escaped but, under interrogation, he revealed their names and [the future Croat fascist dictator Ante] Pavelić’s role in the killing.

This assassination, like all assassinations, did not happen in a vacuum or even in the context of rising tensions between the kingdom's Croats and Serbs. It had been part of a larger movement—though still in its infancy—that would come to terrorize and murder hundreds of thousands in the long-term. But in the short-term, the effect was create unbearable conditions within the Yugoslav kingdom for anyone with a hint of nationalist sympathies. Because the crackdown that came from the new dictatorship under King Aleksandar was fast, brutal, and even cruel; as Misha Glenny writes, “the dictatorship poisoned relations between Serbs and Croats” in its efforts to stamp out all notions of ethnic nationalism and political radicalism not aligned with royal interests, not unlike the external empires of old. As the Croat writer Josip Horvat wrote of the period that followed:

The death of Schlegel became a pretext for [state] terror in all forms. Politics was soon indistinguishable from gangsterism. Legal authority was regularly pushed aside while in its place came the secret police, the military police, the court police, the police of influential individuals with their own gang of informers, agent provocateurs—all with teams of torturers versed in the practices of the Spanish Inquisition and the methods of the tsarist Ochrana […] Bedković [the chief of the Zagreb police] was himself a clinically pathological sadist […] He would personally torture victims, above all women, at night and then, having changed his blood-bespattered clothes for a clean dinner jacket, would attend high society dinners until dawn when he would find a church and confess his sins as a torturer (he would, of course, receive absolution) and then start the whole process again the next afternoon.

If the King believed that this heavy-handed crackdown on the radical elements within his country—which included both nationalists and communists, as well as those aligned with peasant movements across the kingdom—would put a stop to the unravelling his nation was going through as they entered the 1930s, he was sorely mistaken. Only one month after the assassination of Toni Schlegel, the following proclamation was made at a gathering in Sofia, Bulgaria:

We cannot fight these [Serbs] with a prayer book in our hands. After the World War, many believed that we would have peace. […] But what sort of peace is it when Croats and Macedonians are imprisoned? These two peoples were enslaved on the basis of a great lie—that Serbs live in Macedonia and Croatia and that the Macedonian people is Serbian. […] If we tie our hands and wait until the civilized world helps us, our grandchildren will die in slavery. If we wish to see our homeland free, we must unbind our hands and go into battle.

This was from a speech delivered by that same Ante Pavelić, a 39-year old lawyer and staple in Yugoslav politics since 1921 and staunch Croatian nationalist as a member of the Pure Party of Rights. He was to become notorious as the head of the Croatian Ustashe state, the ultranationalist fascist puppet state of the Nazis during the civil war to come, whose forces often horrified and disgusted even members of the Waffen-SS with their brutality against civilians. However, in the 1920s, Pavelić was a ways off from that, despite there being plenty of hints at his innate brutality. During his time in Parliament, he was known to be antagonistic, particularly toward Serbs, and once when a Serb colleague wished him a simple “good night,” he responded with “Gentleman, I will be euphoric when I will be able to say to you 'good night'. I will be happy when all Croats can say 'good night' and thank you, for this 'party' we had here with you. I think that you will all be happy when you don't have Croats here any more.”

Perhaps, therefore, it is not that surprising that Pavelić was the same Pavelić who was revealed to be involved in the 1929 murder of the Toni Schlegel only one month earlier. And it tracks with his previously quoted speech: this was said to a crowd of Macedonian nationalists called the VMRO. This organization, like Pavelić and his fellow Croatian nationalists, wanted to see the new Yugoslav dictatorship overthrown. This desire would only grow with time, especially since Pavelić was feeling these desires from a place of exile. Thanks to King Aleksandar's bans on ethnic and nationalist organizations and parties, labeling them as essentially treasonous to the idea of Yugoslav unity, as well as the arrests of leaders of such organizations, many nationalist figures within the Yugoslav government—namely Croats like Ante Pavelić—fled to other countries. In Pavelic's case, he had fled to Austria, the old enemy of his Serb antagonists. As we saw, he didn't simply remain complacent in his old imperial masters' homeland and went to Bulgaria to make that speech from which we just quoted, effectively appealing for what Misha Glenny calls “the violent overthrow of Yugoslavia and and the secession of Croat lands.”

In 1934, the Ustashe under Pavelić only numbered about 600 members, with Pavelić even being forced into exile in Italy under the protection of fellow fascist Benito Mussolini. But this marginal status and small number should be mistaken for a lack of influence or potential for an existential threat to the Yugoslav kingdom.

King Aleksandar was in Marseilles in October of 1934, paying a visit to France's foreign minister Louis Barthou, when the assassination occurred, creating what Misha Glenny refers to as “the most sensation and unsettling event that year in Europe.” Aleksandar was attempting to cement better relations with France—who was still six years away from capitulating to nascent Nazi Germany—and while he and Barthou were being slowly driven through the streets of Marseilles, a man stepped into the street holding a bouquet of flowers. Before anyone realized what was happening, he jumped onto the car's running board, shouted “Vive le roi!”, or “Long live the king!” and produced a Mauser C39 semi-automatic, and fired multiple shots into King Aleksandar's torso, as well as some accidental ones into the chauffeur. The assassin took off running, firing wildly at the policemen trying to chase him down, and accidentally shooting two innocent bystanders, killing them.

In the chaos, the police had fired at the assassin and managed to accidentally fatally shoot the French foreign minister Barthou, but were eventually able to catch up to the assassin, with one officer on horseback running him through with a sabre and another clipping him on the head with a gunshot, but not killing him. It was actually the crowd of angry bystanders who chased the assassin down and beat him to near death (while the police stood back and watched, it should be noted) that would do him in; he would die later that evening along with Foreign Minister Barthou. After initially having trouble identifying the assassin, the authorities caught a break when, during the autopsy process, they saw the man had a tattoo across his chest: a skull and cross-bones and the letters “VMRO.” It did not take long to identify the man as a Bulgarian nationalist named Vlado Chernozemski, whose tattoo signified his allegiance to the Macedonian-Bulgarian group the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization, which also, not coincidentally in this case, had direct ties to the Ustashe. Ante Pavelić had been one of the conspirators responsible for this action.

The Yugoslav kingdom would hang on by a thread for another seven years. By the spring of 1941, Europe had been engulfed in war for nearly two years, and Yugoslavia’s authorities—governed by the Prince Regent Paul until Aleksandar’s son Peter II came of age—desperately tried to keep themselves out of the fighting, likely knowing full well what would come to pass if they entered the war, by signing non-aggression treaties with the swelling Axis powers, particularly Nazi Germany. After a coup d'état forced out Paul and the royalists, Hitler saw this as a major hindrance to his soon-to-be-executed plans to invade the Soviet Union, and declared war on Yugoslavia. This was despite the fact that the coup plotters had planned to continue the treaties signed with the Third Reich, but Hitler, having flown into one of his characteristic rages, was having none of it.

Belgrade, the kingdom’s capital, fell almost immediately under the might of the Nazi onslaught, with thousands dying. Without wasting any time, Hitler carved up the kingdom, placing the various regions under the control of his more “reliable” allies, while placing the Ustashe and Ante Pavelić in charge of the new “Independent State of Croatia,” where the long-held grievances of Croatian nationalists against the Serb authorities exploded in a years long orgy of bloodletting against Serbs, Jews, Roma, and all others deemed unreliable to the new regime. The concentration camp at Jasenovac more than earned the moniker, “The Balkan Auschwitz” during this time, where most prisoners were worked to death, if not tortured and mutilated by the Croat guards—some as young as 12 years old—simply for the enjoyment of the regime. While no credible evidence ever emerged of a now-infamous claim made by the Italian journalist and writer Curzio Malaparte, there was a rumor that the Poglavnik (or “Fuhrer”) himself, Ante Pavelić, had a basket in his office containing forty pounds of human eyes taken from the Ustashe’s victims.

The dream of Yugoslavia was dead. It would remain dead, despite the attempts by the communist Tito to resurrect it in his own socialist image after the war was over and the Allies were victorious. It was never doomed to failure; there had always been a chance. But circumstances developed that eventually made it impossible. Scholars debate when that moment came, but it is hard to believe that the fate was not sealed when political violence had become so normalized that the assassin Puniša Račić believed it would be a good idea to kill his fellow countrymen in cold blood on the floor of the Yugoslav parliament. There was no reason to compromise anymore. It was now a land of death.

Nothing is preordained in history. However, the famous writer Rebecca Black wrote of her travels across the ailing Yugoslav kingdom in 1937, and despite the fall of the nation still being some years off, she seemed to see the place for what it had become and what it would remain:

I had come to Yugoslavia because I knew that the past has made the present, and I wanted to see how the process works. Let me start now. It is plain that it means an amount of human pain, arranged in an unbroken continuity appalling to any person cradled in the security of the English or American past. Were I to go down into the marketplace, armed with the powers of witchcraft, and take a peasant by the shoulders and whisper to him, “In your lifetime, have you known peace?” wait for his answer, shake his shoulders and transform him into his father, and ask him the same question, and transform him in his turn to his father, I would never hear the word “Yes,” if I carried my questioning of the dead back for a thousand years, I would always hear, “No. There was fear, there were our enemies without, our rulers within, there was prison, there was torture, there was violent death.”

It should go without saying that this is not a position I take, even with my general belief that President Trump is a corrosive force to American politics. I don’t know how many times I have to explain this, but I don’t believe the problems the United States face begin and end with Trump; he is a symptom of a larger issue that implicates everyone.

I have been so upset lately about the exuberance my largely left wing friends and acquaintances have shown over these murders. I’m confused about the inability of people to see the danger of wanting to outlaw “hate speech”, and condoning violence against, or isolation of people who disagree with you. Thank you for using that huge brain of yours to write eloquently what so many of us with we could say.

The Americans who cheer for a civil war should read articles such as the above.

They should consider how awful such conflicts get.

https://thegrimhistorian.substack.com/p/so-you-think-you-want-a-civil-war