The Areo Archives: A New Great Awakening May Be Nigh

This is the third and final installment of the Areo Archives, a trilogy of articles I wrote during the course of 2020-2021 for the dearly departed (but not forgotten!) Areo Magazine. In this edition, we have probably the longest one I wrote for them and, in my opinion, the one about which I am the most proud for multiple reasons.

Those who know me or have followed me for a long time know that I carry within me not just a pretty deep distrust of organized religion, but of the religious impulse itself. It remains to be seen whether or not that is a fair position for me to take—in that, it is certainly possible that religious belief is something innate within human evolutionary psychology—but it is what it is. It’s also been at the core of my distrust of political/ideological possession, in the cruder, more obvious personality cult sense of the Trump phenomenon (at least from around 2016-2021), and in the more sophisticated (and in my opinion, relevant) sense that has, reductively, come to be called “Wokeness” or “Wokeism” (I prefer to simply call them Wokestani Americans).

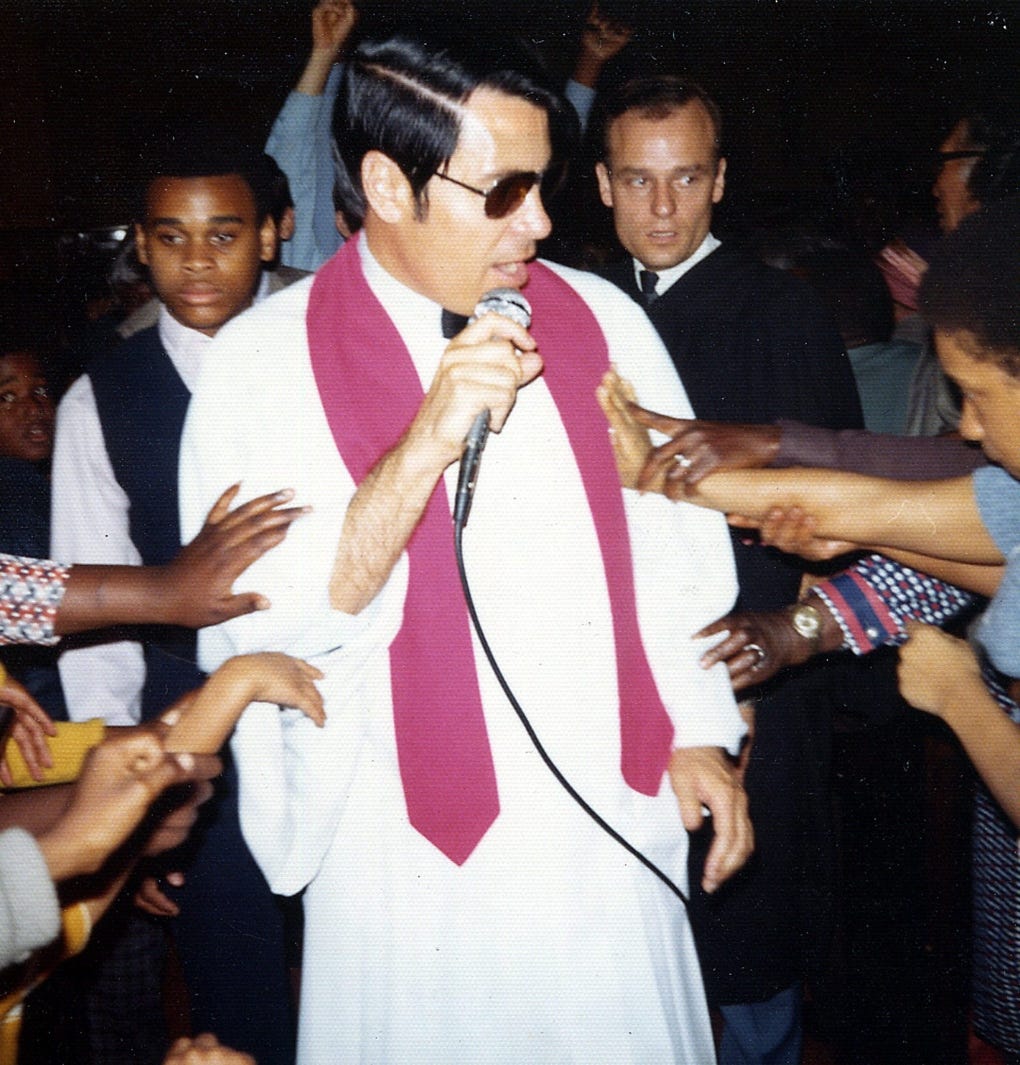

Joking aside, in the wake of January 6th, 2021—which I always saw as a natural culmination of what had already been brewing and even happening across the political spectrum for the previous four years—I wrote this piece exploring the idea that perhaps what we had been seeing, particularly on the political left/left-coded side of American politics, was a deeply religious phenomenon. There were two things that made me think this. The first was this photo:

This image was taken a mere five blocks from where I grew up in Minneapolis, the site of George Floyd’s unfortunate death. Putting aside how deeply perverse it feels even over four years later to look at, it is also deeply revealing: it is clearly a religious rite being done through a supposedly secular lens of racial justice. As the Christian Post reported, “A number of Christian groups that have been holding revival services at the site where George Floyd died in Minneapolis say they're seeing many people turn to God in baptisms and miracles are happening.”

These images were coming out as I was reading the masterful tome of Christian history by Tom Holland, Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World, in which, in the book’s final chapters, he made the parallels between Christian tradition and what we now call “woke” quite explicit. He had written his book a few years before everything that occurred in 2020, but the rhetoric was already quite apparent, especially in the vestiges of what Curtis Yarvin calls “the Cathedral” (or what I prefer to just call “the elite academic-to-professional class pipeline that has always existed in one form or another”). These connections were only made clearer in 2020, with the tent revival atmosphere of the protests and even riots being obvious to anyone who knew even a little about America’s Christian history. This led to me doing some more digging and what resulted in this essay.

As the years have gone by, and as I entered graduate school, this essay’s subject has stuck with me, and I always come back to the same conclusion: I was even more correct than I initially believed. The discourse surrounding atheism’s role (or especially communism’s role) in the decline of religion has always struck me as unimaginative at best, and downright idiotic at worst. However, I grant that unless you read about America’s religious history and how deeply entwined it is with politics and social psychology and our culture’s self-concept, it would be a reasonable assumption to believe that anti-religious rhetoric hurts religion (which seems insecure to me, but whatever). The point is, my views on this have only solidified and it’s a topic that I’m essentially placing at the center of my master’s thesis, but specific to the First Great Awakening and its connection to the Salem Witchcraft Crisis (which, I would be loathe to not add, is actually closer to what was happening in 2017-2020 than an actual Awakening; I suspect the real Revival is still to come). I have adjusted the title to better reflect my views on this subject—namely to reflect the lack of consensus on how many Awakenings we’ve had—but the point ultimately remains the same.

Please enjoy this edition of the Areo Archives.

—AVS

P.S. There are some references that have become dated, and while I’ve done my best to clean those up and/or provide foot-noted context, this will at times read a lot like something written in 2021. However, I still believe the central point holds up.

…

“Nietzsche had foretold it all. God might be dead but his shadow, immense and dreadful, continued to flicker even as his corpse lay cold.”

—Tom Holland, Dominion

The United States of America has had a long and complicated relationship with religion. Religion is more fundamental to America than most believe and that situation is by no means over or predetermined to end, though this may not seem obvious, given that Americans have seemingly never been less religious than they are now. In 2019, the Pew Research Center found that almost a quarter of Americans were unaffiliated with any religion and that 3% and 4% of them were atheists and agnostics, respectively. This was up from the 15% reported by the American Religious Identification Survey in 2008—and touted by Bill Maher in his docu-comedy, Religulous—which was itself already double that of the number cited in the 1990 report.

The reasons for this decline are many—not least the incredible pace of scientific and technological advancement, which has satisfied many people’s desire for immediate wonder. But the decline was also due to the marked increase in beautifully written and logically sound works by members of the so-called New Atheist movement, including such luminaries as the late Christopher Hitchens, Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris and Daniel Dennett and amplified by YouTube videos of their debates with religious figures—the kind of events that would previously have only been available to ticket holders or viewers of Book TV. These interactions revealed just how shaky the logical and moral foundations of religion—particularly Christianity—actually were, especially in the face of neo-Enlightenment arguments. This had already been clear since at least January 6th, 2002, when the “Spotlight” article exposing the widespread rape and abuse of children within the Catholic Church hit the front page of the Boston Globe. It was therefore unsurprising when, eight years later, Hitchens defeated former British Prime Minister Tony Blair in a debate over whether religion was a force for good in the world (a loss that Blair himself conceded). Irreligiosity was growing—and in some ways seems to be still growing—and many non-religious folks became understandably complacent.

Unfortunately, they may be about to face a rude awakening.

Many of the New Atheists—including Richard Dawkins and Sam Harris—seem to have accepted that religion is probably here to stay, despite declining church attendance and the statistics referenced above. This doesn’t mean that the New Atheists have given up their fight. However, some of the recent trends in the supposedly secular world have taken on an increasingly religious character, showing that growing irreligiosity seems to lead to an increase in spiritual yearning.

Take Jordan Peterson, for example, whose guru-like appeal to his dedicated audience, mostly comprised of young men, has a distinctly religious character. Many claim that he has changed their lives. During a mass event at Liberty University in 2019, a young man rushed the stage as Peterson was speaking. “My name is David,” he said, “I’m unwell, and I need help … I just wanted to meet you!” The man collapsed in tears. Peterson walked over to him and began speaking to him off-mic and rubbing his shoulder. Judging by subsequent comments and articles about the event, this touched a chord. According to Peterson’s former colleague Bernard Schiff, the psychologist once wanted to purchase a church. That seems apt.

But, despite Peterson’s reverential overtures about the “metaphysical truth” of Christianity, his following is probably less interested in religion than in him. However large his audience, Peterson alone hardly explains the current spiritual yearning. The other factor here is social justice.

A New Religion

Despite a founding member’s claim that the organizers of Black Lives Matter are “trained Marxists,” the social justice movement has a distinctly religious character. As John McWhorter writes, “Antiracism is now a religion. It is inherent to a religion that one is to accept certain suspensions of disbelief. Certain questions are not to be asked, or if asked, only politely—and the answer one gets, despite being somewhat half-cocked, is to be accepted as doing the job.”

Over the years, as opposition to the Trump administration and support for movements like Black Lives Matter has grown, it has become increasingly clear that social justice is more than just a political phenomenon. This isn’t just because of the fervor of its adherents, nor does it mean that the movement has no secular power. But observant Christians like Andrew Sullivan have noted similarities between the devout of both main factions—Trump supporters and antiracists—and cult followers:

The need for meaning hasn’t gone away, but without Christianity, this yearning looks to politics for satisfaction. And religious impulses, once anchored in and tamed by Christianity, find expression in various political cults. These political manifestations of religion are new and crude, as all new cults have to be. They haven’t been experienced and refined and modeled by millennia of practice and thought. They are evolving in real time. And like almost all new cultish impulses, they demand a total and immediate commitment to save the world.

But, however fervent the support for Trump and despite the events of 6 January, it pales in comparison to the spiritual yearning that suffuses the rhetoric of western leftist social justice movements, as Jonathan Haidt, Douglas Murray, Coleman Hughes, Helen Pluckrose, Josh Szeps, Peter Boghossian, Sam McGee-Hall, and many others have observed. This makes sense. After all, as Sullivan puts it, “We are a meaning-seeking species.”

Rudderless twenty-somethings at elite colleges and under- and unemployed twenty-somethings trapped in their homes during a pandemic with nothing but rage-filled social media to keep them company might well panic when the meaningless of their lives finally hits home. George Floyd’s killing and the subsequent consensus of righteous outrage must have given some of them a rush of purpose.

Of course, some people are sympathetic to social justice ideas and committed to reducing racism, but uncritical or unaware of the movement’s more clerical, fundamentalist aspects. It’s understandable that social justice adherents should focus on the unsatisfactory outcomes that persist despite the huge legislative gains made over the course of the twentieth century in protecting the rights of disenfranchised populations. But the movement lacks self-criticism and promotes totalizing explanations more concerned with examining the soul and character of humanity than proposing meaningful reforms. In this it is unmistakably illiberal. It masks religious zeal as secular politics. We can see this in the pronouncements of people like educational theorist Bettina Love, who wrote in 2020 that “We need therapists who specialize in the healing of teachers and the undoing of Whiteness in education.” Some hear echoes of China’s Cultural Revolution or the Khmer Rouge in proclamations like this one. I hear echoes of Jesus camp, Scientology and even Jim Jones.

As Robert Jay Lifton has explained in his book Thought Reform and the Psychology of Totalism, human beings can easily succumb to cults. Social justice makes use of many of the methods of totalizing ideologies: milieu control, i.e. complete dependence on specific methods of communication; behavioral manipulation for some greater, usually mystical or spiritual purpose; demands for purity and confession of sin; “sacred science” (e.g. “this theory isn’t up for debate,” or “it’s not my job to educate you”); loaded language and especially the prioritizing of the doctrine over the person and what Lifton calls “the dispensing of existence,”: i.e. the idea that the individual matters less than where they are placed within this ordering of the world. Anyone who falls outside the order should heed the words of torturer O’Brien to Winston Smith in 1984: “You do not exist.”

As Tom Slater has written, “identity politics is in many ways more spiritual than material. Heretics must be ousted. Blasphemies must be scrubbed. Past sins must be ‘come to terms with,’ in some vague, undefined sense.” That social justice is a religion is now, surely, beyond doubt. So where will it go from here?

The end game will probably not be as simple as a mere fizzling out or as dramatic as a complete balkanization of the United States—though these are both distinct possibilities. To get a clearer picture of how things might turn out, we must look to America’s past. As Tom Holland writes, “In a country as saturated in Christian assumptions as the United States there could be no escaping their influence, even for those who had imagined that they had.”

Revival: American as Apple Pie

Andrew Sullivan has commented:

And so the young adherents of the Great Awokening exhibit the zeal of the Great Awakening. Like early modern Christians, they punish heresy by banishing sinners from society or coercing them to public demonstrations of shame, and provide an avenue for redemption in the form of a thorough public confession of sin.

There have been at least two Great Awakenings in U.S. history; that is about as much consensus as one can find, but it’s also been argued that there have been more, with four periods of time seeming to herald a rise in religiosity, however transient it might ultimately be. As Sam McGee-Hall has pointed out, “America goes through cycles of religious panics” and “through a series of historical circumstances peculiar to the US, these periodic religious panics have, over centuries, been transformed into an unconscious ritual complex.” Hence, I tend to believe that we can ascribe four Great Awakenings to the United States’ history.

The United States’ long, complex relationship with Christianity stems from the tensions between its Christian origins as a colony and its fundamentally secular official foundation. We took the most religious English Christians of the early seventeenth century, let them establish a new home in the so-called New World and then, when they eventually became a united nation nearly two centuries later, their new society was codified by men who said things like “In every country and in every age, the priest has been hostile to liberty.” This created a tug of war between fundamental ideals that only increased as the culture of the growing United States became ever more heterogeneous.

As mentioned, scholars differ as to how many Great Awakenings America has had. It depends what you define as an awakening. Religious revivals have occurred throughout American history, beginning with the first Great Awakening in the early eighteenth century, about four decades before the American Revolution. Clearly, there was no United States at that time, but there was a growing philosophical undercurrent that would come to characterize its founding and the thirteen colonies were by no means as theologically homogeneous as the societies formed by the Puritan arrivals had originally been—and even the Puritan colonists had not been an ideologically harmonious group.

The first Great Awakening was largely the work of revivalist preacher Jonathan Edwards, grandson of the Puritan Solomon Stoddard. In the sermons that ushered in the Northampton Revival of 1734–35, Edwards attacked various ideologies including, most importantly, Enlightenment ideas, which he regarded as fundamentally incompatible with his own Calvinist interpretation of God as an absolute sovereign, who could never be questioned and could only be understood through complete piety and submission to his will. In other words, no matter what the individual did in life, it was God who would ultimately decide whether or not he would be saved. As Edwards proclaimed in his sermon “Sinners at the Hands of an Angry God”: “There is nothing that keeps wicked men at any one moment out of hell, but the mere pleasure of God.” This fatalistic approach appealed to many of the colony’s young people and around 1,000 new converts joined Edwards’ church.

Emboldened by the growing success of his preaching, Edwards began to study the process of conversion. In his essay “A Faithful Narrative of the Surprising Work of God in the Conversion of Many Hundred Souls in Northampton,” he highlights the four major steps toward conversion. First, a person develops an interest in Christianity and hopes to avoid damnation by following its creed. Then, when it becomes clear that the sinner cannot live up to the standards laid out in the Old Testament, he believes that he had committed what Edwards calls “unpardonable sin.” Then, he realizes or, as Edwards puts it, he will “awaken”—or “get woke,” if you will—to the fact that salvation is not impossible but inevitable through Christ’s sacrifice. Finally, the convert experiences a “new light” within himself and—without even being consciously aware that he has been converted—becomes a true servant of god.

Edwards’ ideas had profound effects on colonial American society—not all of them positive. As the revival spread across New England, it became clear that this path to salvation wasn’t going to end well for everyone who embraced it. Bouts of insanity broke out at some of the more emotionally charged events. People saw visions and had mystical experiences. Some of these shocked even Edwards himself, but he also saw them as part of the path towards an understanding of God’s glory. By Edwards’ own account, “multitudes” of congregants were so convinced of their own sinful damnation that they killed themselves. There are only two confirmed cases of such suicides, but some historians have found circumstantial evidence of many more. One even cites the “suicide craze” of the 1730s as a major reason for the initial decline of the first Great Awakening. A second wave occurred in the 1740s, culminating in Edwards’ infamous “Angry God” sermon and resulting in the initial growth of Evangelicalism. But it is the first wave that suggests explanations as to why this awakening occurred to begin with.

One major reason was the decline in church attendance in early eighteenth-century New England and another the influence of Enlightenment rationalism, which led many educated people to turn to less pious forms of religious practice, such as Unitarianism and deism, and even led some to become atheists. This incentivized preachers from around New England to begin their calls for revival. At first, they only attracted small, local crowds. Some historians have suggested that the pursuit of increased wealth, especially among the land-owning class, distracted the early settlers from the usual forms of piety. The dwindling church attendance may also have been a result of the increasing atomization of spiritual life in the colonies over the previous century, since the Quakers, Anglicans, Presbyterians, Baptists and others all advocated their own paths to salvation. But things changed in 1727, when an earthquake struck off the coast of New Hampshire and Massachusetts, splitting the ground, shaking the foundations of buildings and injuring and frightening many. The causes of earthquakes were still little known, but it didn’t take long for the clergy to convince many people that this was the act of an angry god. Amid the malaise of a potentially meaningless existence, the locals were literally shaken free of their belief that they were in control of their lives. In many ways, this would set the template for all the Great Awakenings to come.

The second Great Awakening, in the early-to-mid nineteenth century, was similar to the first in many ways, but had a more recognizably American character. Its messaging was far more populist—many of the lower classes got involved, as did blacks and women. But the biggest trend was the rise of more fundamentalist and separatist Christian sects, most of which originated in the region of western New York known as the burned-over district. The second Great Awakening was more American. The first had been largely confined to the more literate class of colonist. The second was characterized by resentment towards elites. Its tent preachers were plain-spoken and, as historian Chris Jennings explains, rejected “traditional denominational authority.” Like Martin Luther’s reformation three centuries earlier, this was about bringing the word of God to the people, by the people.

The most famous of the sects to come into being during these seismic shifts was the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, better known as the Mormons. Mormonism began as a cult, especially under its most nefarious leader, Brigham Young. While the Millerites and the Adventists simply took a more hardline stance on Christian teachings, the Mormons managed to subvert the entire Christian theology in a way that hadn’t been seen since the writing of the Qur’an. They gave the Bible a sequel, which not only explained mysteries like the origin of Native American tribes, but placed America at the center of Christian myth. While the idea of manifest destiny provided a convenient religious justification for America’s westward imperialism, Mormonism provided the “real” explanation of America’s origins. It was the nineteenth-century’s very own 1619 Project.

The increasingly disparate movements of the second Great Awakening arose for reasons similar to those that led to the first: increasing schisms within preexisting belief systems, declining church attendance, abject human suffering and a natural disaster followed by periods of economic uncertainty. In 1815, the largest volcanic eruption in recorded history occurred in Indonesia. The explosion of Mount Tambora produced the infamous 1816 “Year Without Summer.” Almost immediately afterward, economic calamities began to occur one after another, culminating in the panic of 1837. As historian Michael Barkun has observed, these calamities gave many Americans “a special receptivity to millenarian and utopian appeals.” However, there was more to this than simple existential fear: the disenfranchised and enslaved suffered the most and resented the elites as a result.

Many of the increases in church attendance during the second Great Awakening were due to women converts, who, at least one source has claimed, outnumbered male converts by three to two. Historians can’t agree on the reasons for this imbalance. Perhaps the economic insecurity hit harder among women or perhaps many American women had simply had enough of being treated as if they had no minds of their own and being expected to follow their husbands’ influence in everything. Indeed, many husbands disapproved of these conversions, seeing them as a threat to familial stability.

It is easy to understand why black slaves were drawn to the religious revival, especially after the religiously motivated slave uprising led by Nat Turner in 1831. Some Baptist ministries, in states like South Carolina, were started by slaves, largely as a way for black people to come together as a community and cope with the hardships of their day-to-day existence. We can see the second Great Awakening as the first marriage between Christian devotion and social justice. It would by no means be the last.

The third Great Awakening spanned a much longer period than the first and second. Like them, it focused on devotion to Christ and to American identity, but it also incorporated a more explicit renewed focus on contemporary social and even secular issues. Some historians reject the notion of a third Great Awakening because of the prominence of these more secular concerns, but this seems naïve. After all, as the second Great Awakening showed, there is no incompatibility between secular populism and Christian revivalism: in this movement, they complemented each other.

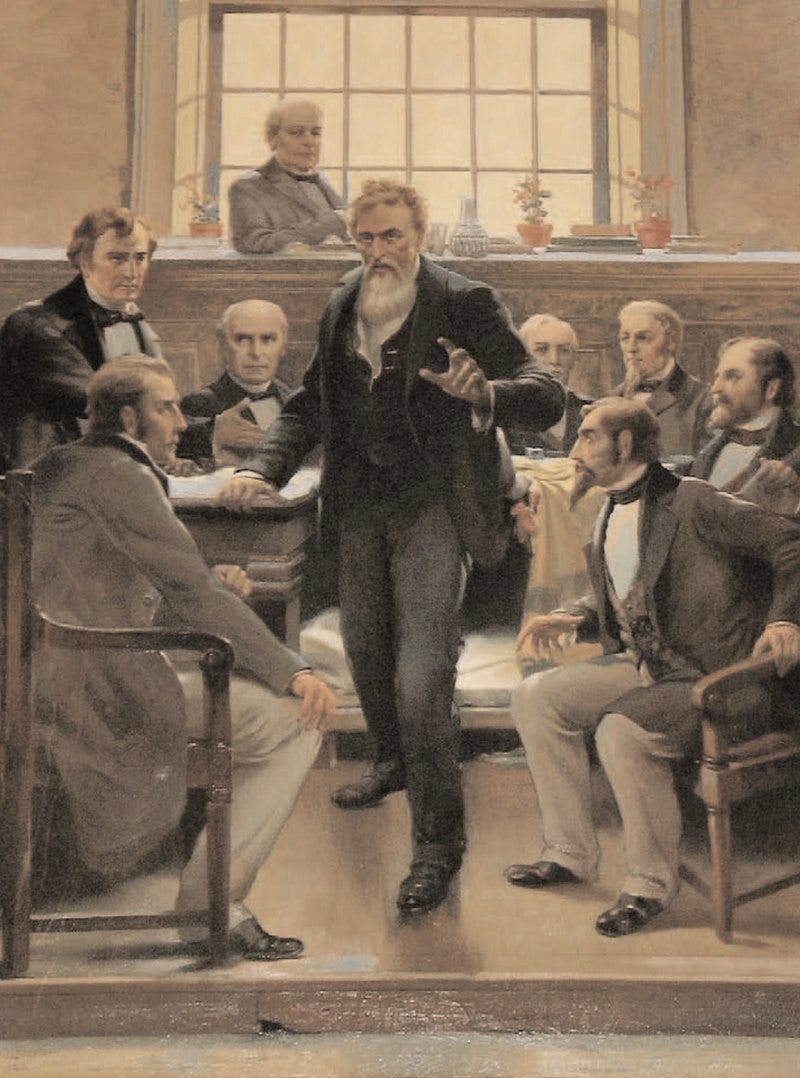

During the third Great Awakening, the latest causes among Christians were the abolition of slavery in the 1850s–60s—Frederick Douglass’ Methodist preachings and John Brown’s fire-and-brimstone approach were part of this—and the prohibition of alcohol in the 1910s. The temperance movement also influenced the movement for women’s suffrage. And, as in the second Great Awakening, there emerged yet more atomized religious groupings that began as cults, including spiritualist and occult movements such as Thelema and theosophy, as well as more seemingly legitimate denominations like the Jehovah’s Witnesses and the Christian Science movement. There were also non-denominational splinter groups, such as the Chautauqua movement founded by the Methodists, which prioritized more secular aims, especially adult education.

All this religiosity was spurred on by external forces that placed individuals under pressure: the nineteenth-century wars, including the Civil War; extreme economic hardship due to the first great depression, which began in 1873; and an increasing wealth gap between rich and poor. Added to this were even more explicitly political issues, including growing distrust in government institutions and a rapid rise in immigration that led to increased labor tensions. While many Americans turned to secular populist demagogues like California’s infamous Denis Kearney—whose racist antics were partially responsible for the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882—many Americans looked to God and his preachers for salvation. Many of these preachers decried the excesses of the gilded age and proclaimed that rich industrialists like Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller were in league with the devil himself.

After the First and Second World Wars, America experienced a spiritual deadening. There had been so much suffering and uncertainty—caused not only by the wars, but by the 1918 flu pandemic, the Great Depression of the 1930s and the uncertain beginnings of the atomic age—and yet the future looked bright. The economy was booming, technology was improving exponentially and everyone was buying homes and having families, ushering in the baby boom. Life was too good to worry about the wrath of God. But the complacency of the privileged could not hide the fact that, despite geopolitical victories, an economic boom and a general sense of optimism, plenty of Americans were being left behind and even held back.

It’s no coincidence that Martin Luther King Jr. was a preacher who took Christ as his gospel and his example. However, as the past Great Awakenings had shown, American religious movements don’t necessarily remain purely religious for very long. The social-justice-inspired spiritual fulfillment King promised gave way to disillusionment after his execution in 1968. What could have begun the fourth Great Awakening was cut short and soon replaced by a highly secular political radicalism, the likes of which America had not seen for nearly a century.

What followed was widespread violence, domestic terror attacks by groups like the Weathermen and the kidnapping of heiress Patty Hearst by the leftist terrorist group the Symbionese Liberation Army. Although most of the activism was motivated by opposition to the Vietnam War, which was seen as the epitome of rapacious western imperialism, the radical movement increasingly devolved into abject nihilism, resulting in a swath of drug addicts, rape victims and single mothers. As Darryl Cooper has observed, many of the casualties of the radical movement of the 1960s and 1970s began, in their aimless wanderings, to end up in cults, the most infamous of which was Jim Jones’ People’s Temple, which united an extreme socialist ideology with proclamations from scripture.

When these cults began to self-destruct, many people probably felt as if there was nothing left. But in what was to become known as the Bible Belt, preachers like Billy Graham were beginning to make a name for themselves and movements like Pentecostalism were gaining followers as never before. Raucous displays of speaking in tongues, hysterical weeping in the presence of the holy spirit, faith healing and even prophecies were making a comeback after nearly two centuries. The spiritual void that had gripped America for the past half century was over. The Republican Party took notice and used this momentum to get the Evangelical-backed Ronald Reagan elected to the presidency in two landslide elections. In 2005, one could hear the last echoes of that fourth Great Awakening when George W. Bush claimed that God himself had told him to end the tyranny in Iraq.

It may seem hard to imagine that another Christian revival could take place anytime soon after such a brazen display of pious warmongering. And yet, as we have seen, America’s Christian legacy has a funny way of reasserting itself at the most unexpected times.

The Emerging Awakening

Early twenty-first-century victimhood culture is rooted in Christian values. As Tom Holland writes:

The measure of a man’s compassion for the lowly and the suffering comes to be the measure of the loftiness of his soul. It was this, the epochal lesson taught by Jesus’ death on the cross, that Nietzsche had always most despised about Christianity. Two thousand years on, and the discovery made by Christ’s earliest followers, that to be a victim might be a source of power, could bring out millions onto the streets. Wealth and rank in Trump’s America were not the only indicators of status, so too were their opposites. Against the priapic thrust of towers fitted with gold plated lifts the organizers of the Women’s March sought to invoke the authority of those who lay at the bottom of the pile. The last were to be first and the first were to be last.

Indeed, as Holland later writes, “The retreat of Christian belief did not seem to imply any necessary retreat of Christian values. Quite the contrary.” Holland views America’s twenty-first-century culture war as “a civil war between Christian factions,” while Sam McGee-Hall argues that “the outbreak [of personally transformative manias like social justice] will lead to collective disappointments or tragedies.” Neither of these observations are wrong. The tragedy of Jim Jones’ People’s Temple—in which a concern for racial social justice was weaponized by a drug-addled megalomaniac who convinced nearly 1,000 people to kill themselves—is evidence enough of what can go wrong when social justice takes on a religious character. But neither Holland nor McGee ask what this means for American Christianity itself. Given America’s history of religious revivals, we may be witnessing the opening stages of a fifth Great Awakening, which, like its predecessors, could result in an explosion in the numbers of churchgoers.

Of course, no one can predict the future. There may be no fifth Great Awakening (or whatever number it might be by now). The social justice craze may either fizzle or flame out in ways no one has predicted. However, America seems to be undergoing a religious and political reorientation. During the fourth Great Awakening, which began as the radicalism of the 1960s began to wane, the Republican Party opportunistically scooped up millions of adherents and made it their mission to show an entire generation that the GOP was their political home—something many still believe in parts of the United States. This could happen again. However, the GOP is currently frantically trying to reorient its public image in a post-Trump world and, while still on friendly terms with American Evangelicals, it no longer reflects the values espoused by George W. Bush and Ronald Reagan. It’s now the left that is expressing more interest in matters of the soul, even though that interest is refracted through a secular, political lens.

The increasingly spiritual terminology used by much of the antiracist, intersectional, social justice crowd, especially in the wake of George Floyd’s death, will surely have a powerful effect on the many online keyboard warriors who have been under lockdown and suffering from relative social isolation for nearly a year now. Soon, a swath of young leftists may emerge, looking for any way to replicate the online communities in which their views have been incubating. Meet-ups won’t cut it, and neither will Tinder. Loneliness was already an epidemic long before Covid-19. After a year of being socially distanced, that loneliness will probably result in a lot of desperation—especially among the left, who have been generally more committed to adhering to lockdown orders and will therefore face a particularly tough uphill battle when they have to re-acclimate to normal social life. The only places that offer relief from social isolation and don’t require proactive planning and scheduling are churches.

Imagine how attractive churches could be to these isolated, largely non-religious people who have clearly been suffering from profound psychological turmoil, if the significant increases in substance abuse and mood disorders are anything to go by. Now imagine how effective these churches could be at attracting these people if they adopt the language of social justice, which, as we know, is compatible with Christian teachings, as evidenced by Christianity’s history in America. In other words, it may be less that churches will go woke, but that the woke will go Christian. There may be a rise in Christian religiosity—perhaps of a left-leaning character. The woke are already spiritually inclined. They are concerned with things like sin and repentance, and—if their ideology matures out of the need for crude, performative vengeance—redemption. Then the transformation will be complete and Christianity in America will take on a new aspect, meeting needs that can’t be satisfied by the secular world—full as it is of fallible, unreliable human beings, unfair structures and systems, greed and opportunism. If enough individuals fail to achieve the aims of the social justice left, there will be a further move towards the literally infallible, i.e. God.

However, this prognostication may be wrong. Social justice has had powerful effects on culture, media and the marketplace. None of these will guarantee social justice’s longevity—as we can see from capitalism’s numerous failures to cash in on cheap, digestible, low-resolution social justice principles, from the Ghostbusters remake of 2016 to the attempted reboot of Charlie’s Angels in 2019. Woke culture is largely determined by the market and markets are only as woke as consumer behavior demands. If the adage get woke, go broke is true and if social justice falls out of fashion—and it probably will, as average Americans begin to tire of being hectored by the woke elites many have grown to resent during this pandemic—the true believers in social justice will be faced with a choice: fade quietly away or double down. And, once they lack the cultural force to back up their truth claims, doubling down and sounding like an out-of-touch has-been extremist will seem far less attractive than simply adapting to the new culture trends. We cynics might then be proven right and the whole social justice project might be revealed to be a massive, performative, emotional Ponzi scheme that is making ever fewer people a lot of money, while encouraging the rest of us to distrust and hate each other on the basis of immutable characteristics. If this happens, Christianity will remain the domain of the right and the left will continue to search out the latest progressive trends.

The likelihood of a Christian rebranding of social justice—the completion of our new Great Awakening—is all the greater if the social justice movement fails: because people are highly motivated to avoid cognitive dissonance and the cognitive dissonance experienced by someone who has invested more than a decade of her life in the cause of social justice would be profound. In addition, there are likely to be growing incentives to distance oneself from the increasingly corporate side of social justice. The cynical, performative nature of corporate social justice flies in the face of spiritual social justice and many people hate corporate power as much as they love social justice.

But all effective activists are opportunistic, keen to grab whatever power and influence they can get. Many activists aren’t going to relinquish their influence over media and corporate America out of some vague commitment to principle. For a split between the corporate and the spiritual aspects of the movement to occur, the unholy alliance with capitalism needs to have a negative effect on true believers. That could come about in many different ways. It could be result of a subtle cultural shift or of a massive economic collapse. Or perhaps enough social justice folks will feel the brunt of cancel culture to realize that their aims could be better served outside the movement: namely, in a place of worship, where spiritual and even existential meaning can be married to civic and political concerns. All it would take would be one influential church pastor, who welcomed disenchanted social justice warriors into his or her flock. The future could be inhabited by a piously Christian left and fervently anti-clerical right. In the years to come, everyone, especially those on the non-religious left, will need to decide between a commitment to the Enlightenment-era values of freedom from religion and freedom of thought, or to the modern, progressive demands of social justice. Given the historical instability of social movements that remain untethered to stable preexisting belief systems, such as Christianity, this will be the final litmus test of the twenty-first-century social justice movement.

Perhaps the notion of oppression will become so atomized that the intersection is reduced to the individual and everyone who calls themselves intersectional will realize that they have been anarchists all along, concerned with absolute individual liberty. The events of January 6th, 2021 could result in the GOP’s wholesale rejection of Trump and Trumpism and renewed pursuit of the Christian vote.1 But perhaps, instead, the social justice left will turn to the church and disseminate their views from an actual pulpit.

As Douglas Murray astutely argued, the big problem with intersectional leftism is the dearth of forgiveness to be found within the movement. This lack will either lead to widespread despair and even suicide or a search for something that will absolve guilty people of the existential sin they believe they are guilty of because of their whiteness, complicit silence or privilege of any kind. The woke are true believers in original sin. And, if you are a true believer, the only solution to original sin of this kind is the vicarious redemption offered by god’s son.

Areo Magazine, January 25th, 2021.

Obviously, this did not age well.