The Vital Truth About Rhetoric and Violence

There is no clear link, and even if there is, it doesn't matter

“The tongue has no bones but is strong enough to break a heart. So be careful with your words.”

—Unknown

“My own opinion is enough for me, and I claim the right to have it defended against any consensus, any majority, anywhere, any place, any time. And anyone who disagrees with this can pick a number, get in line, and kiss my ass.”

—Christopher Hitchens

…

Something surprised me when I started formally studying history in graduate school almost one year ago: that the idea of correlation not equaling causation was not a dictum. To be fair, when examining history, it is next to impossible (or perhaps just very difficult) to dig out causal links, especially the further back in time you travel. If journalism is the first draft of history and manages to get this wrong so often, what does that say about history? Regardless, it was still a bit of a surprise for me, having a background in psychology—particularly research-based psychology—in which the drum of “correlation does not equal causation” was banged upon in every single class.

In fact, in the history of psychology course I took, the main takeaway was that psychology, in its infancy, had a major causal fallacy problem (just look at most of the stuff Freud produced, or the totally-not-ghoulish Philip Zimbardo of Stanford Prison Experiment fame). These days, psychologists and psychological researchers—at least those worth their salt—are careful to explain what evidence suggests, and therefore where future research can go from here, either to refute or replicate the results. In other words, a good study has a good and thorough (and honest) conclusion section.

I bring all this up because former (next?) President Donald Trump survived an assassination attempt on July 13th, 2024.

Wait, what? What did all this have to do with that?

Well…

These are just a sample of the masses of tweets and commentary that continues to proliferate less than a month after the failed attempt at blowing the former President’s head off. And they all share one common thread, seen in bold lettering in the images I’ve provided. As in, this situation happened because of the rhetoric that people on the left (both in media and in general) have been using for the last nine years.

To be clear, I do believe that the depictions of the former President have been, to put it mildly, pretty hysterical over the last nine years or so. Invocations of “fascism” and especially “Nazism” being applied to him have never made much sense to me, even with what has been revealed about his electors shenanigans after the 2020 election. Obviously, those are the signs of someone who does not respect the democratic process, yes, but fascism requires much more than just not liking democracy. And to imply that he is so sinister we’d soon see millions of our own countrymen (not to mention the countrymen of our neighbors, who we’d be bound to invade in this strained analogy) herded onto cattle cars to be shipped to industrial gas chambers? I don’t know, I never much liked Donald Trump as the President, but that seems pretty damn insulting to the millions of victims to the Third Reich military machine (not to mention, again, hysterical).

I also don’t think that the growing hysteria from the post-MAGA Republican camp (the populists? the New Right?) is particularly salient either, especially when they start talking about LGBT issues and other things that are, frankly, no more their business than a progressive’s weird fixation on J.D. Vance’s crime of miscegenation-while-conservative. Attempts at creating a barrier between the state and parents via the public school system while using shaky evidence about “harm reduction” are certainly creepy in their implication and should probably be unacceptable in all but the most extreme contexts, but…“groomers”? “Marxist and Luciferian incantations”? We’re really going with these kinds of things?

The point is, if we try to limit insane or even just factually incorrect speech because some crazed person might have responded to such speech (and it is not even clear as of this writing that the would-be assassin of Donald Trump was), we’re trying to kill flies with sledgehammers (or crates of explosives, if we really want to run with this analogy). And yet, people still try. And it’s hard to blame them; while there was no shortage of unhinged imagery and rhetoric directed at George W. Bush and Barack Obama from 2001-2016, it’s likely fair to say that the persistence, intensity, source, and scope of the inflammatory rhetoric has since increased. But that does not address the real question that I want to approach, both as a budding historian and as someone with a moderate background in research-based psychology.

That core question is this:

Did violent, existentially-framed rhetoric cause former President Trump to be almost assassinated?

…

The question of whether or not violent rhetoric causes an attempted assassination is part of a broader question of whether or not rhetoric causes violence in general. Even more broadly, it is part of a question over whether or not rhetoric causes behavior to occur, positive or negative, at all. It’s a simple question, and seemingly one with a simple answer.

I would wager that most people, using what they believe is common sense, would say yes. What I would also wager is that saying “yes” would correspond almost perfectly with their political beliefs. They believe that positive rhetoric (say, Greta Thunberg’s impassioned speech in 2019 regarding the existential threat of climate change) causes people to behave well. They also believe that negative rhetoric (say, Trump’s speech on January 6th, 2021) causes people to behave badly. In other words, people will attribute the positive or negative effects of rhetoric based on what they believe is right and wrong.

To further flesh out this example, someone who believed that Greta Thunberg’s 2019 speech was inspiring and helped make people more animated about the threat of climate change would be unlikely to believe that her rhetoric caused the more unhinged climate activist behavior of the past five years—like defacing priceless art and archeological sites. Conversely, someone who believed that Donald Trump’s speech on January 6th, 2021 directly inspired the Capitol Riot that day would be unlikely to believe that his calls for peaceful dispersal and for protesters to go home had any effect on anyone’s behavior whatsoever. Whether or not anyone in these scenarios has a point doesn’t matter to the broader point: that it is a form of attribution bias—specifically fundamental attribution errors—that more likely informs our moral judgments rather than rational, situational considerations.

However, as suggested, this does not put to bed the claim that rhetoric causes violent behavior. According to an article published by the Brookings Institute only three months after the January 6th, 2021 riot, “a range of research suggests the incendiary rhetoric of political leaders can make political violence more likely, gives violence direction, complicates the law enforcement response, and increases fear in vulnerable communities.” They do indeed cite several papers (and self-described experts) which suggest that rhetoric “emboldens” people to express what they define as hateful attitudes, but there is nothing in the data that suggests anything more significant than this kind of correlation.

In other words, any evidence which shows that changes in behavior was caused by inflammatory rhetoric is, at best, circumstantial. In fact, the article even acknowledges at the top of its fourth paragraph that, “There is no direct line between violent rhetoric and political violence if the speakers are careful not to name specific targets and means,” the best example of an awkward mumble in article form if there ever was one. The key part of that statement—that as long as no specific target and means are labeled, the direct line cannot be established—is a key part of this puzzle. The point is, despite making a sneakily-worded claim that rhetoric “connects” to violent behavior, the article’s author Daniel L. Byman is unable to make the case that rhetoric causes behavior, despite the implication of causality being created by letting “connects” do so much heavy lifting.

A more honest accounting of the facts comes from an article on LiveScience, written back in January of 2011, in the aftermath of another story to which we will return. The author Stephanie Pappas explains that psychologists make it very clear that “the answer isn't as simple as yes or no,” and that while “violent rhetoric can make people more comfortable with the idea of violence […] it's almost impossible to pin down the larger causes of one specific incident.” [Emphasis mine]. This might seem like a cop-out when it comes to explaining the causes of something seemingly straightforward, but it’s important for us to remember that just because something seems like common sense, does not mean that it is therefore true.

For example, while it’s clear from research cited by Pappas in her article that “people with acute mental disorders like schizophrenia or bipolar disorder are two to three times more likely to commit violent crimes (not just homicide) than people without mental illness,” it’s also clear that other factors play a part, including substance abuse, which correlates with violent behavior at rates eight to ten times greater than that of the population. These factors matter for our purposes because they are completely independent of the presence of violent rhetoric and yet act as risk factors for violent behavior.

While it might not seem unreasonable to “tone down” violent rhetoric as a means of trying to stem a tide of violent behavior, there are a number of reasons this is pretty unnecessary. In terms of it being unnecessary, Pappas notes in her piece that “there hasn't been any systematic research on whether rhetoric pushes people on the edge of sanity off the cliff” and that “the phenomenon is so rare that it would be difficult to get good data.” To quote a University of California—Irvine psychologist named Peter Ditto from the Pappas article, “You’re never going to get science to speak to whether some sort of violent political rhetoric caused this particular individual to [act as they did].” This is backed up by a 2012 study from the University of Michigan, which found that political advertisements which used words associated with violence (think words like “fight”) had little effect on an individual’s opinion on whether or not political violence was justifiable. In addition, any positive effect that was observed by the researcher was more strongly correlated with individuals who already possessed high levels of aggression. In other words, the violently worded rhetoric did not make anyone violent who was not already primed for being violent to begin with.

If only to hammer the point home a little more strongly, these kinds of findings also track with the data that I gathered while doing my own research 15 years ago on the effects of violent media exposure on adolescents. In terms of the research I examined, there was very little evidence to suggest that violent behavior stemmed significantly from exposure to violent media, though there was plenty of evidence strongly suggesting that exposure to real-world violence—namely environments in which domestic violence, gang violence, and war violence—produced a very real positive effect on an individual’s likelihood of committing violent action at some point in their lives. This was supported by a study conducted in 2006 by McCabe and colleagues, and from earlier work done in 1996 by Saner and Ellickson; the former found that “exposure to community violence significantly predicted […] externalizing problems two years later when potential confounds were controlled,” and the latter found that “as the number of risk factors increases, so does the likelihood of engaging in violent behavior.”

If it was not yet clear that violent behavior stems from much more than second-hand exposure—that is, violent media and rhetoric—it becomes even clearer when examining how biological and cognitive factors have also been determined as being significant in predicting violent behavior relatively independent of environmental pressures. According to a study conducted by J. Martin Ramirez in 2002, psychobiological factors like hormonal levels—namely higher levels of testosterone, primarily in young natal males—demonstrated a significant link to violent behavior with adolescents that continued into adulthood. As Ramirez reports, “early adrenal androgens contribute to the onset and maintenance of persistent violent and antisocial behavior, and that it begins early in life and persists into adulthood,” concluding that “hormones can be involved in the development of aggression as a cause, as a consequence, or even as a mediator.”

In addition, according to a study conducted back in 1984 by L. Rowell Huesmann and Leonard D. Eron, aggressive behavior remained stable over time, in which “a circular process in which scripts for aggressive behavior are learned at an early age and become more firmly entrenched as the child develops, so that aggression becomes self-perpetuating in children with certain cognitive characteristics.” This further suggests that aggression—that is, violent behavior—is something far more entrenched than something that can just be “activated” by the presence of violent rhetoric. In other words, much of the evidence available suggests that human brains, while certainly malleable over time and with proper pressures applied (some of which are biological and likely have a genetic component), are not so putty-like that someone shouting “fight” at a rally will prompt a violent response.

In other words, from the evidence that is available trying to study the effects of exposure to violent media and rhetoric, there is, at best, no clear answer, which requires us to assume a non-positive effect. This is not to say we should not continue to study such linkages for the sake of expanding our knowledge on the effects of speech on behavior, but it is to say that we cannot start ascribing responsibility to speech where none conclusively exists.

In terms of external, social factors, the studies we examined above all concluded the same thing: that the risk for violent behavior increases thanks to exposure to other violent behavior, but often only in children’s and adolescents’ immediate vicinity (i.e. not via media consumption). The only significant and persistent effect media consumption had upon children—and these were very young children, often toddlers—was that it sometimes desensitized them to violent depictions when they were exposed to it again. In other words, there was a diminished reaction toward the violence. The question then, of course, becomes, “does this desensitization toward violent expression lead to a greater propensity toward violent behavior?” The problem is that this leads us to a frequent (and classic) chicken-and-egg paradox in psychology: would someone desensitized by violent depictions in media already be someone who is more likely to engage in violent behavior thanks to other factors (both biological/genetic and environmental), or did this violent depiction exposure “push them over the edge”?

As best I can tell, in the decade and a half since I conducted my own research, no further data has emerged that suggests exposure to media—including rhetoric—can accomplish this on its own. In fact, thanks to the research that has been conducted suggests the opposite. The previously cited Huesmann and Eron write that “violent scenes [seen on television] provide examples that the child can encode,” and that children “rehearse aggressive acts through aggressive fantasy, and these aggressive acts undoubtedly include the ones viewed on TV.” However, despite this study demonstrating a link between cognitive processes and violent behavior, it fell well short of demonstrating those cognitive processes being determined by exposure to violent media, much less being persisting across time independent of other factors. According to a much more recent study by Devilly, O’Donohue, and Brown published in 2021, anger and aggressive behavior was much more strongly correlated with personality factors and feelings of frustration than with exposure to violent media. As Devilly himself put it in an interview about these findings in the Griffith University news story covering the study:

We found no difference in both anger and aggression following exposure to a book, violent video game, television and non-violent video game. What we did find was that people with high levels of impulsivity, increased emotional reactivity to the media, and frustration with the content of the media are more likely to have a higher anger response to media exposure. These results are in direct opposition to traditional models of aggression which suggest a causal link between trials of violence and aggression risk.

This study has essentially found what many other studies have found over the past several decades: that violent media exposure demonstrates little to no significant connection to the incidence of violent behavior. What makes this frustrating for a lot of social scientists (and no doubt some of you reading this piece) is that while it doesn’t demonstrate a positive effect, it doesn’t demonstrate a negative effect either. Because to be fair, these kinds of results to these studies also means that you cannot say with any certainty, on a scientific basis, that violent media or rhetoric exposure doesn’t cause particular behavior to occur. The real key thing to remember is that the lack of a positive claim does not, therefore, negate the negative claim; that is what trips a lot of people up (i.e. “Well there’s no evidence that rhetoric causes violent behavior, but there’s no evidence that it doesn’t; ipso facto we might as well assume it does!”).

This kind of response is at the heart of a “correlation = causation” fallacy. Some of my favorite examples of this fallacy at work can actually be found on Wikipedia, including:

Young children who sleep with the light on are much more likely to develop myopia in later life. Therefore, sleeping with the light on causes myopia.

As ice cream sales increase, the rate of drowning deaths increases sharply.

Therefore, ice cream consumption causes drowning.

A hypothetical study shows a relationship between test anxiety scores and shyness scores, with a statistical r value (strength of correlation) of +.59. Therefore, it may be simply concluded that shyness, in some part, causally influences test anxiety.

Or what will always be my personal favorite: The number of films Nicolas Cage has appeared in a given year has a positive relationship with how many people drowned by falling into swimming pools in that same year. Therefore, Nicolas Cage film releases cause people to drown in swimming pools. …Then again, I did almost trip and fall into a pool after watching Mandy and Pig back to back…

Joking aside, the truth is, there are too many variables for which we must control when studying the phenomenon of media/rhetoric consumption to say for certain. In order to explain how difficult this would be, let me list what needs to be controlled in an experiment seeking to determine the singular, causal effects of violent media/rhetoric consumption:

The genetic incidence of behavioral disorders that are positively correlated with aggressive behavior toward others (e.g. antisocial personality disorder, psychopathy, bipolar disorder).

Self-perpetuating cognitive connections between violent behavior and thought patterns.

Socioeconomic hardship when growing up.

Exposure to violence in the real world, including different kinds of abuse, bullying, urban violence, and warfare.

The point should be clear: unless you can control for all of these things (and likely other factors I’m not smart enough to think of) while conducting a study of people’s propensity toward violence when exposed to violent media or rhetoric, you cannot—at least if you’re a good and honest researcher that isn’t searching for a particular conclusion—say with any certainty that rhetoric causes particular behavior to occur.

However, there is a deeper reason that, at least until such evidence appears and is conclusively replicated, we should not be wringing our hands over the effect of rhetoric. And perhaps, even if we can determine a strong causal link, perhaps we still shouldn’t.

…

So does rhetoric cause violence? That is the million dollar question.

Or perhaps, should we be treating the expression of rhetoric—violent or otherwise—as something that can meaningfully affect behavior? Despite the psychological evidence appearing pretty damning against the idea that there is such an influence, it’s still not as clear as I would like it to be in order for me to definitively say, “no” on the basis of human psychology alone.

However, to my mind, the practical answer is a definitive “no.” An outright, flat-out no, based both on this lack of compelling evidence from the psychological literature and, more importantly, on the profound legal history on the subject of speech protection.

The practical implications of claiming that rhetoric—i.e. speech—is what causes violent action are (or should be) simple. This is because even if the casual link between rhetoric and violence wasn’t extremely tenuous, there is a profound legal and even moral perversion at work if we acted as if rhetoric caused violence. And frankly, I don’t think anyone understands this better than the head of the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (as well as co-author of the excellent The Coddling of the American Mind and it’s semi-sequel, The Canceling of the American Mind), Greg Lukianoff.1

Greg has been providing incredible commentary on this subject for years. In an excellent recent post over on The Eternally Radical Idea Substack discussing this very subject, Greg made it very clear that this argument—of speech constituting violence—“needs to die.” As he explains, “Anyone who equates speech and violence has likely never been punched in the face,” and that “equating a barbed tongue with a barbed spear not only betrays a lack of understanding of genuine violence, but also the way words — even harsh ones — have served as both an alternative and a solution to violence.”

This is the core moral issue with claiming that rhetoric causes violence, because it is, in effect, saying that rhetoric is violence, and thus, should be subject to legal punishment akin to the punishment of actual (that is, physical) violence. And if that is the case, well, then we know who is really responsible for the attempted assassination on former President Trump. Or, perhaps more controversially, then we know who is really responsible for the chaos that occurred on January 6th, 2021. As we’ve already covered, these kinds of claims simply do not hold water when it comes to human psychology. But they also hold little to no water when it comes to the long, and vital-to-understand history of free speech protections in the United States legal system.

While Greg is the real expert on such a subject (and he does great work summarizing some examples in his previously-linked article), I need an excuse to make this essay on my nominally history-based newsletter more about history, so I think it would only be fair to apply some historical analysis of the free speech debate in the United States to demonstrate why arguing for rhetorical responsibility for violent behavior—again, already shown to be dubious at best earlier in this essay2—simply does not pass muster (for anyone who values free expression, at least).

In his article, Greg mentions a couple vital cases in the history of free speech rulings, including the infamous Watts v. The United States (1969) and Walter H. Rankin, etc., et al., Petitioners v. Ardith MacPherson (1987), both of which involved inflammatory speech against the President (Johnson and Reagan, respectively). These cases demonstrated that, at least by 1969, our freedom to say extremely inflammatory things (such as the Watts of Watts v. The United States proclaiming, “If they ever make me carry a rifle the first man I want to get in my sights is L.B.J.”) was actually quite robust. Yes, these cases went to the Supreme Court, but they both worked out in favor of the defendants thanks to their First Amendment rights. However, things were not always this certain.

The road to what I, for a long time, have called the “post-Brandenburg world” (referring to a famous case to which we’ll return), has had many twists and turns that many have not and still do not fully appreciate (and I include myself, a legal layman, in that). There are many incredible books that cover these twists and turns, both broad and specific, but the one that has helped me most in coming to understand this journey through the American court system is the 1998 opus The Shadow University: The Betrayal of Liberty on America’s Campuses by Alan Charles Kors and Harvey A. Silverglade, the co-founders of the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE).3 Kors and Silverglade’s history is comprehensive and vital for understanding the journey free speech has taken in the United States.

To begin, Kors and Silverglade describe Gitlow v. New York (1925), in which Benjamin Gitlow, one of the founders of the Communist Party USA (and future anti-communist crusader thanks to, like many similar to him, newfound post-Stalinist disillusionment), was convicted for spreading pro-revolution pamphlets, which was ultimately upheld by the Supreme Court. This might seem like an obvious loss and indeed, Kors and Silverglade explain this first major victory of the ACLU in 1925 as “Pyrrhic,” but the ruling incorporated the Fourteenth Amendment by arguing that its provisions of due process also applied to local state authority as well as federal authority. As Kors and Silverglade summarize, “Despite Gitlow’s loss, the incorporation of First Amendment rights into Fourteenth Amendment ‘due process’ proved vital to the development of free speech jurisprudence.”

This standard would be solidified just over a decade later with Hague v. Committee for Industrial Organization (1939), in which the ACLU was able to challenge an anti-organizational ordinance passed in New Jersey against the CIO (i.e., the “CIO” of the AFL-CIO mega-union we know and love today) that prohibited them from distributing leaflets and organize meetings. As Kors and Silverglade explain, this secured the “public forum” doctrine of free speech protections, thanks to Justice Owen Roberts “[holding] that the parks and streets where the CIO and others were speaking were held ‘in trust’ for the public as a forum in which to exercise the rights of speech. Local governments no longer could restrict speech because they controlled the land upon which the speaker stood.” If you’ve ever heard someone say “I pay taxes,” as a way to defend their right to say vile things on publicly-owned land, they may be obnoxious but they are absolutely correct.

Kors and Silverglade also devote a lot of space to explaining how the litigious pursuit of loopholes in these free speech protections actually helped fuel plenty of cases that helped create the incredible free speech protections we enjoy today in the 21st century. As they write, “The history of First Amendment jurisprudence has been written by the efforts of those who have sought to whittle away free speech rights by positing one exception after another, and by those who have resisted.” This has resulted in the Supreme Court consistently hearing four special types of cases against what we consider free speech in the United States. Two of these exceptions—namely those of “obscenity” and threats to “national security”—are less relevant to this essay and honestly, will likely open up enough cans of worms on their own, so we’ll leave those be. The exceptions that matter most to the question of whether rhetoric and behavior are connected are, in Kors and Silverglade’s words, “speech posing a ‘clear and present danger’ of imminent violence or lawlessness,” and “so-called ‘fighting words’ that would provoke a ‘reasonable person’ to an imminent violent response.”

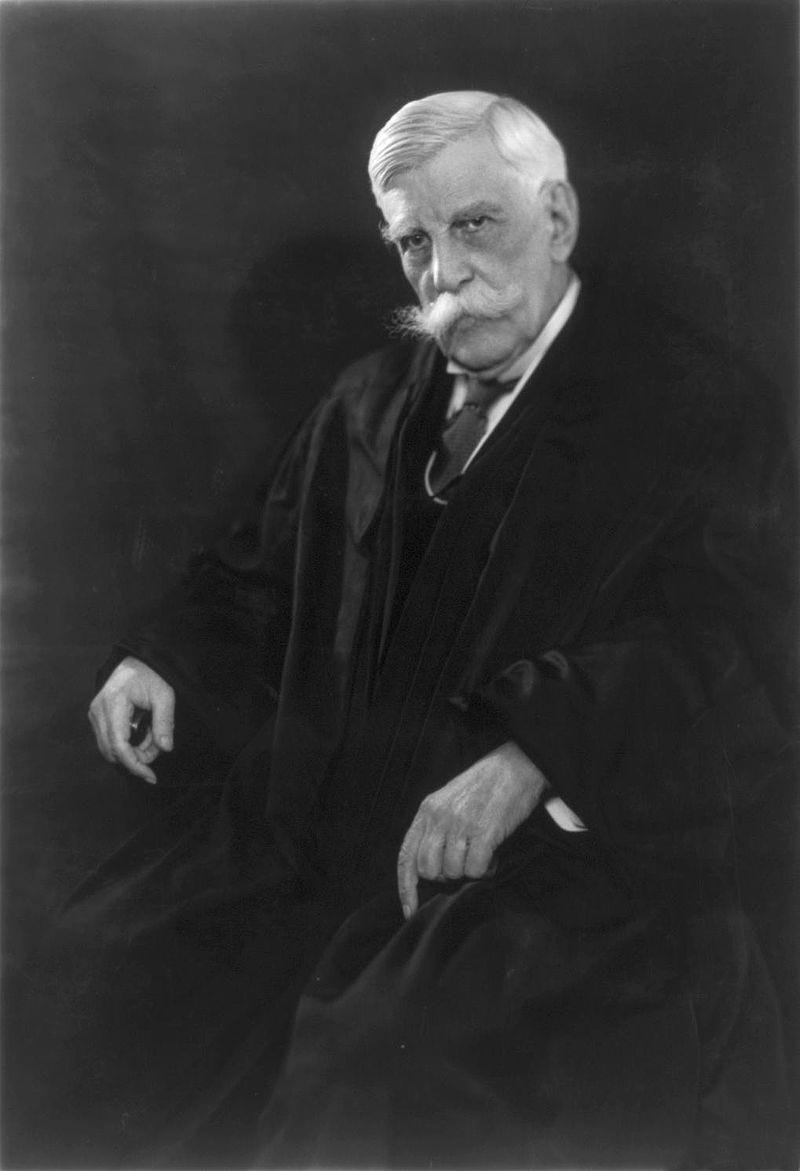

The “clear and present danger” exception first arose in the infamous Schenk v. United States (1919), in which Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes claimed that First Amendment protections were a moot point when words were “used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent.” The part of Holmes’ opinion most of us are familiar with is his proclamation that “The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theater and causing a panic.” This standard was kept in place for a half-century until the most famous free speech case of the 20th century, Brandenberg v. Ohio (1969), began the process of putting limits on these attempts at limiting free speech on the grounds of “clear and present danger” standards.

There is a reason that the Brandenburg case is considered such a landmark in the expansion and protection of Americans’ freedom of speech (and a reason that I still sometimes use the term “post-Brandenberg world,” though I’ve come to think that more credit is due to subsequent cases too). That is, this case began the process of whittling away anti-speech activists’ ability to go after their targets for their advocacy of distasteful ideas for fear of “incitement” (there is that word again!). Obviously, people have continued to claim that unseemly speech will “incite” others into action all the way to 2024 and likely will continue to do so well into the future, but outcome of Brandenburg v. Ohio began a process of strengthening the standards required for such legal outcomes to occur. And there are likely people who, when they hear the things the Brandenburg of this case was saying, would like to see him not just thrown in jail, but perhaps strung up on a lamp post.

Clarence Brandenburg was a leader of a Ku Klux Klan chapter in rural Ohio in the 1960s. He had organized a rally in Hamilton County and invited a Cincinnati reporter to come cover the proceedings. During the rally, captured on two separate films, Brandenburg proclaimed that, “Personally, I believe the nigger should be returned to Africa, the Jew returned to Israel,” and that, “We’re not a revengent organization, but if our President, our Congress, our Supreme Court, continues to suppress the white, Caucasian race, it’s possible that there might have to be some revengeance taken.” Thanks to the, to say the least, inflammatory remarks made by Brandenburg, he was arrested and charged under the Ohio criminal syndicalism law, in which “crime, sabotage, violence, or unlawful methods of terrorism as a means of accomplishing industrial or political reform,” and assembling “with any society, group, or assemblage of persons formed to teach or advocate the doctrines of criminal syndicalism” was deemed illegal.

The case, when it appeared in front of the Supreme Court, was eventually overturned. The reason being, it was clear to the Justices that the remarks made by Brandenburg merely advocated for the objectively racist policies and violent action, but not in any set time or place. This was where the more modern standard of the “imminent lawless action” test came into being, which made the notion of “clear and present danger” far stricter as far as standards went. In other words, unless Clarence Brandenburg had been holding his rally on, say, a street in Cincinnati, and directed the KKK members at his rally to go attack a random passerby who happened to be black, his invective was indeed protected.4 This new standard was applied only four years later in Hess v. Indiana (1973), and it reaffirmed and clarified the imminent lawless action test established by Brandenburg. Ever since then, the standard has continued to be used and continues to be strengthened to the point that, as Kors and Silverglade put it, “mere advocacy ceased being the repeated target of censors.”

However, would-be censors had another exception that, despite seeming less well-known than the notion of “shouting fire in a crowded theater” (in the sense that it doesn’t seem to be referenced as often), has become an even more common weapon against free speech. That is the supposed exception of “fighting words,” which Kors and Silverglade explain us “a doctrine honored in constitutional law more in theory than in practice.” It began with a case that, by today’s standards, seems pretty open-and-shut, in which a man named Walter Chaplinsky was arrested after getting a crowd in Rochester, New Hampshire riled up when, shouting from a street corner, he proclaimed that conventional forms of religion (as opposed to his Jehovah’s Witnesses faith) was “a racket.” After he was escorted away by a police officer for his own safety, he railed against the city marshal of Rochester, calling him a “god-damned racketeer” and a “damned fascist” and that the local government was made up of “fascists or agents of fascists” (seeing as this was 1940, this charge meant more than it does today). Chaplinsky was arrested and charged for violating a law that prevented him from saying “any offensive, derisive, or annoying word to any other person who is lawfully in any street or other public place.” In Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire (1942), the Supreme Court upheld this conviction, with the majority arguing that “there are certain well-defined and narrowly limited classes of speech,” and that Chaplinsky had violated these classes by using “insulting or ‘fighting’ words—those which by their very utterance inflict injury or tend to incite an immediate breach of the peace.”

As we can see, even the Supreme Court—at least eighty years ago—agreed with the idea that words constituted a form of violence (or, in their words, “injury”). Chaplinsky was not able to see his free speech rights affirmed by the Court and the Court reaffirmed the idea that speech could be made illegal in the name of public safety with this decision. However, this decision, with its invocation of “fighting words,” set into motion future nuances and expansions of what constituted free speech. Only one year after Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire was decided, the Court contradicted its own “fighting words” standards in their decision on Cafeteria Employees Local 302 v. Los Angeles (1943). In their ruling, the Court decided that the word “fascist” was “part of the conventional give-and-take in our economic and political controversies,” weakening their own previous ruling, but strengthening the protections on free speech in the process.

However, the first truly significant change occurred in 1949, when, as Kors and Silverglade put it, “the Court further undermined the idea that offensive speech is not protected.” They continue:

In Terminiello v. Chicago, [the Supreme Court] reversed the disturbing-the-peace conviction of a suspended Catholic priest and follower of the notorious anti-Semite Gerald L.K. Smith. Father Arthur Terminiello gave a speech in Chicago attacking “Communistic Zionistic Jews,” moving an unsympathetic crowd to violence against him. Justice [William O.] Douglas wrote that the “function of free speech under our system of government is to invite dispute. It may indeed best serve its high purpose when it induces a condition of unrest, creates dissatisfaction with conditions as they are, or even stirs people to anger.” Thus, the Court sent a message that the First Amendment prohibits the punishment of words merely because they might produce an angry reaction. Terminiello was particularly important, because the offensive language there, even though it in fact produced a violent reaction, was not viewed as “fighting words.” [Emphasis added].

The significance of this ruling, and subsequent rulings (like Street v. New York (1969) and Cohen v. California (1971), which involved flag burning with the former, and anti-conscription agitation with the latter) that reaffirmed the core principle of it, should be obvious, but in case it isn’t, consider it this way: under the protection of these cases, even if violent rhetoric caused or even significantly contributed to violent behavior, then, as best I can tell, neither progressive media outlets or Democratic politicians referring to Donald Trump as an existential threat to democracy or a fascist incarnate would be liable in the 2024 attempt on his life. The same can more than likely be said, at least by my best estimation, about Donald Trump’s speech to his supporters on January 6th, 2021.

An important aspect of the Cohen v. California ruling that must be added to all of this is the fact that constitutional protection was extended to the “emotive function” of speech, in which the Court powerfully ruled that “expression of emotion was as much a function of speech as was the ‘cognitive’ role,” according to Kors and Silverglade, because, according to the Cohen decision, “[emotive function] may often be the more important element of the overall message sought to be communicated.” Who can honestly say that emotions have not been and were not running high among the commentariat throughout the entire Trump presidency or during the 2024 campaign, much less in the mind of the soon-to-be-ex-President at the January 6th, 2021 rally?

After the Terminiello, Street, and Cohen decisions—as well as other decisions, like Gooding v. Wilson (1972)—many other convictions involving inflammatory language got reversed, helping set precedent. In legal terms, this is basically like replicating the results of a study, in the sense that these standards continued to pass muster across time and justices. These standards continued and continue to be challenged every step of the way. That is ultimately the point of First Amendment law: challenges to free speech never end and they never will. As Steven Pinker recently put it in an interview on the Free Press’ Honestly podcast, not only is consent of the governed not particularly intuitive in the context of human nature, neither is the notion of free speech itself. There is a reason people like Greg Lukianoff and others rightly say that freedom of speech must be defended. Assaults upon it are eternal because human nature is the only true eternity.

In a way, these challenges should not end, because that would mean that free speech has, in effect, ended. The power of free speech can be seen in the challenges against its very existence. As long as the ability to make those challenges and to challenge those challenges still exists, the experiment that is free speech—and one could argue, American culture itself—will continue.

…

In the immediate aftermath of the attempted assassination of Donald Trump, there was an outpouring of seemingly principled callouts against violence and praise at the idea of using our words instead of our fists. This was right, if only by accident. And conversely, there was and continues to be plenty of people claiming that had the idea of a Trumpian fascist nightmare not been spread, then none of this violence would ever have happened. The hypocrisy at the core of all of this was and remains apparent. The people who entertained the idea that words were violence in the first place suddenly realizing that real world violence was what was truly beyond the pale; the irony was as thick and smooth as butter. And the people who were mocking the “words are violence” crowd only days earlier, were suddenly wringing their hands over the existential tenor or hysterical tone of the rhetoric that supposedly led to the former President almost being assassinated; the irony is just as thick.

And yet, despite this obvious hypocrisy coming from either camp, it should be clear after everything we’ve covered, that none of it matters. It doesn’t matter for actual psychological reasons, and it doesn’t matter for broader legal and moral reasons.

Let’s look at one more story from our past, but our more recent past. On January 8th, 2011, U.S. Representative (D-Az.) Gabby Giffords was in a Tucson, Arizona supermarket parking lot meeting with her constituents, when a lone gunman opened fire and shot 18 people, including Giffords with a point-blank gunshot to the head. Giffords survived, but six others, including Federal District Court Chief Judge John Roll, were killed. The event was horrifying and it quickly became (and largely remains) one of the centerpieces to the gun control movement in the United States (and indeed, Representative Giffords has spent much of her post-Congressional public life advocating on behalf of this cause).

However, while the gun control debate it sparked sucked most of the oxygen from the room in 2011 (which strangely feels kind of passé in 2024), there was a now-very-familiar refrain going on: that political rhetoric, particularly “violent” political rhetoric caused this to happen and needed to be “cooled down.” Specifically, former Vice Presidential candidate (remember that?) Sarah Palin, along with the relatively nascent Tea Party movement, became the target of the political left’s ire for her website called “takebackthe20” that used animated cross-hairs to indicate which U.S. districts needed to be, well, “taken back” (that is, electorally, by Republicans). Giffords had already expressed outrage at this a year earlier in March of 2010, when, after her office had been vandalized, she said, “We’re in Sarah Palin’s ‘targeted’ list, but the thing is that the way she has it depicted, we’re in the crosshairs of a gun sight over our district. When people do that, they've got to realize that there are consequences to that action.” Thus, the pump was already primed for a massive amount of confirmation bias when the actually unthinkable occurred ten months later.

While much of the commentary both at home and abroad seemed to echo this common sense notion that “there are [lethal] consequences” to political speech, there was some vital, if somewhat muted, dissent. It began with the fact that it wasn’t even clear if Giffords’ would-be assassin even saw the map on Palin’s website to begin with. But soon it expanded to more meaningful and philosophical commentary about how inflamed rhetoric was by no means unique in American history, by no means to blame for what happened to Giffords, and by no means even a bad thing.

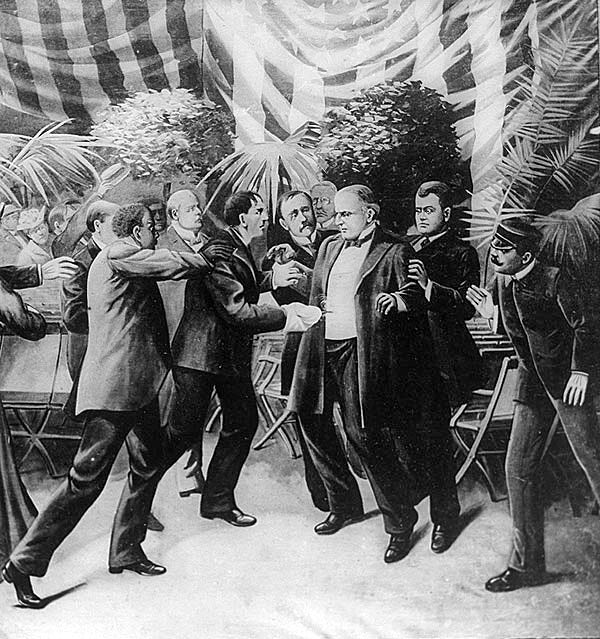

As communications professor and journalist W. Joseph Campbell pointed out in his own historical reckoning of blaming “overheated commentary” for assassinations, the effort to link Palin’ and the Tea Party’s rhetoric to the Giffords shooting was “evocative of a campaign more than a century ago to blame the assassination of President William McKinley on the yellow press of William Randolph Hearst.” Continuing, Campbell writes:

McKinley was fatally shot in September 1901 by an anarchist named Leon Czolgosz, who, according to [William Randolph] Hearst’s finest biographer, was unable to read English. Even so, Hearst’s foes—notably, the New York Sun—sought to tie the assassination to ill-advised comments about McKinley that had appeared in Hearst’s newspapers months earlier.

One especially ill-considered comment helped fuel the allegations: That was a quatrain written by columnist Ambrose Bierce 20 months before McKinley was shot on September 6th, 1901, while greeting well-wishers in Buffalo. Bierce’s column of February 4th, 1900, closed with a reference to the assassination a few days earlier of the Kentucky governor, William Goebel. Bierce, a prickly and acerbic commentator, wrote:

The bullet that pierced Goebel’s breast

Can not be found in all the West.

Good reason: it is speeding here [to Washington]

To stretch McKinley on his bier.

Quoting from the New York Sun’s own story, “A Menace to Our Civilization,” Campbell points out that the paper accused Bierce, the Hearst paper, and by extension Hearst himself of enabling “an atrocious Anarchistic assault on the President” and that yellow journalism had just “graduated into a serious and studied propaganda of social revolution.”

Does this (or, for that matter, the reaction to the Giffords shooting) sound familiar?

Now, despite all this evidence marshaled here, one might still ask more in an abstract, philosophical sense: “Are you saying that you value the freedom for people to express themselves more than preventing harm or ensuring public safety?”

Yes.

And, if you’ll pardon me paraphrasing the Joker meme format, I’m tired of pretending there are any compelling counterarguments against this stance that interest me.

Not only was or is any of this discourse on blaming rhetoric for violence nothing new in American history, but it’s also—if I dare risk falling prey to a naturalistic fallacy—a good thing. As Jack Shafer brilliantly put it in his article on the Giffords shooting and the role (or lack thereof) of political rhetoric in violent behavior, “Any call to cool ‘inflammatory’ speech is a call to police all speech, and I can’t think of anybody in government, politics, business, or the press that I would trust with that power,” and that “The great miracle of American politics is that although it can tend toward the cutthroat and thuggish, it is almost devoid of genuine violence outside of a few scuffles and busted lips now and again.” This is an important reality check, especially in the context of the dreaded 24 hour news cycle (whose 24 hour nature is less of a concern to me than the spotlighting effect it creates on outliers, but…this essay has already grown unwieldy enough). Shafer’s best point, however, and one that I think matters most to what we’re trying to uncover here is this: “The wicked direction the American debate often takes is not a sign of danger but of freedom.” I can’t think of a better way to justify the broader point of this tangled, snarled attempt of mine at explaining why rhetoric doesn’t really matter—materially—as much as so many people think it does.

To recap: the psychological evidence that rhetoric causes behavior, much less violent behavior, simply does not exist. And that doesn’t actually matter because even if it did, we would be sacrificing the one thing that really makes the United States special as a nation and as a culture. This is demonstrated by the repeated expansions and protections applied to the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. The legal system, for generations now, has demonstrated a willingness to continue what was ultimately the experiment the Founding Fathers thought we might put forth as a nation, a culture, a civilization. Given the sophistication of the Bill of Rights, it’s clear that they understood—or at least intuited—that human psychology was more complex than A—>B causality, especially when it came to the question of speech and action. Psychological evidence seems to bear this out; should our legal system and standards not also match what is indeed real and true?

Of course, none of this is to say that such things can’t or shouldn’t be challenged, but it is not insignificant that with every landmark legal case regarding the individual citizen’s right to free expression, his or her protections have expanded. Perhaps the advent of new technologies like artificial intelligence will require a more careful reading on such things—the AI deep-fakes of individuals (including public figures) being placed in pornographic contexts without their explicit consent strikes me as a good example of something that requires deeper legal and moral analysis—but in the meantime, when it comes to the question of rhetoric and behavior, the debate is and should be, in essence, closed.

Further study of the connection (or lack thereof) between rhetoric and behavior must absolutely continue, if only because it will help us make better sense of the greatest mystery of all (that is, the human mind). But again, regardless of the findings of such studies, if Americans are to consider ourselves unique among the rest of the world’s nations and cultures and maintain the reputation as a land of true freedom, then restrictions or referenda on the subject of broader speech restriction essentially render the entire American project moot. While I will always be the first person standing in line to proclaim that the United States is not as special as so many of its appraisers and critics alike seem to think (especially when it comes to comparing it to other countries’ behavior), I will also always proclaim that there are things that Americans do and try that are unique. Our experiment with expanding just how much our citizens are legally allowed to say (and thus think) is one of those things. And to put it bluntly, our legal protections for our speech are not something any American would like to see curtailed if they ended up on the wrong side of that curtailment.

So why will there no doubt be people who read this that are unconvinced by the evidence I’ve provided and the reasoning I’ve suggested? While it is certainly possible that it will be due to evidentiary oversights on my part—I have read only so many psychological studies on this subject after all—it goes back to that pesky lodestar we all have within us, that is, common sense. It is really hard to override common sense. Especially when it feels like what I’m saying doesn’t comport with what we want to be true. If we look at how a lot of people who don’t like the polarization in our political culture or the tenor of the rhetoric in it respond to such events, it almost always becomes reduced to arguments about how “it certainly doesn’t help things,” or even “well, it makes things less pleasant.” These things can certainly be true, but at the end of the day, that is still just one person’s opinion. When I hear someone say, “it doesn’t help things,” or “it makes things less pleasant,” I know what they mean and might even sympathize, but I also think those arguments, given the evidence out there, need to be put to bed because the implication will always be, “we need to put a stop to that speech that we think is bad.” Otherwise, what’s the point of saying you don’t like the speech? If you have a deeper argument against things feeling unpleasant, let’s hear it. But I suspect it will mean very little. There are a lot of things we don’t like but can’t (or, as I hope I have made clear, shouldn’t) do anything about.

If only it was so simple; that the young man who shot at Trump (or the one who shot Reagan, or the one who shot Kennedy, or the one who shot McKinley, or the one who shot Garfield, or the one who shot Lincoln) was motivated by pure brainwashing of a hostile, partisan media, then we could find some justice where there seems to be none having come from the Secret Service blowing his brains out. Maybe then we could pin the necessary responsibility, maybe then we could place a lid on the specific kinds of rhetoric that led to this outcome, so it would never happen again. Maybe then the left or the right could finally take real responsibility for things they said so flippantly, and the problem of left or right terrorism could be finally put to bed, and we’d all be safe from the people on the other side of the political aisle who hate our fucking guts.

If only it was so simple.

A quick admission for the sake of transparency here. As far as I am concerned, Greg is a true mensch for one reason alone: he has been recommending this Substack for close to a year or so, and this recommendation has been significantly responsible for the relatively rapid growth I’ve been seeing here. But more importantly, I see Greg as the true point-man for defending free expression in the United States from a legal perspective, especially given the sorry state in which the ACLU has found itself over the last decade or so.

Just a reminder for those of you still fuming about me implying Donald Trump’s rhetoric was not responsible for the events of January 6th, 2021, or that Democratic rhetoric about “threats to democracy” did not cause the shooter to take his shot on the former president on July 12th, 2024.

Formerly the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, and currently headed by Greg Lukianoff.

It should be noted that this kind of specificity has been plaguing the debate surrounding President Trump’s role in the violence of January 6th, 2021, and as best I can tell, there still is no consensus. I have already stated my own opinion on such claims as they relate to the psychological aspect of this article, but legally speaking it still appears to still be gray.

The word violent can mean destructive so in that vein there is such a thing as emotional violence. Obviously the comparison to physical violence should be greatly discouraged but I do think that at least some people using the label “emotional violence” are simply describing emotional abuse, which does exist.

I agree with the idea that hate speech should not be proscribed without a clear credible and at least somewhat immediate or highly specific threat or incitement underpinning it but I don’t think you’re considering any of the bigger picture such as does an aggregate of venomous speech create a critical mass that actually does affect individuals who likely are already troubled but being bathed in confirmation of their worst fears and beliefs, are tipped over the edge. I would not dismiss this possibility especially considering the structure of social media to cocoon people and feed them repetitive streams of what they are most interested in and often repeated validation of their ideas.

Another important point to consider- does an aggregate of venomous speech desensitize people to the violence of others when the actor is “on their side” or “in their camp.” I don’t mind presidential assassination jokes so long as they’re funny but I was taken aback by the wellspring of rather sociopathic not jocular responses to the Trump assassination attempt and of course I don’t think all these posters are sociopaths but I do find myself concerned that they don’t mind at all representing themselves in this way. What implications this has and to what extent I don’t know but it’s worth studying. I suspect the sums of venomous speech do stunt moral reactions.

I would never dismiss the force of venomous speech when it’s spreading across populations. To ignore that would be ahistorical and frankly dangerous. The mechanism through which this might empower an already unstable person or someone with poor coping abilities or someone who grew up hearing very disturbing ideas I do think relates to ironically (given the common profile of the enraged loner) feeling part of a group or a mission larger than oneself. The effect is magnified by social media.

I also believe that when harassment is protected under the banner of free speech, you remove a critical boundary that may then empower someone to become physically violent or destructive. The main reason we protect free speech even on the margin is because to not protect it requires an arbiter (as it is literally impossible to outline infinite examples of what is or isn’t okay into credible consistent categories and have a consenus) and we’ve seen enough examples of what happens when self interested arbiters are in control. The assault on hate speech as something to be reigned in is only one side of the coin. The other side is replete with bizarre breaches of laws and norms under the banner of free speech- invading private property to give a protest lecture, forcing others to listen to you, things of this nature. The boundaries of how people express themselves have to be delineated and these are eroding as well. an Ozzy Osborne song didn’t drive someone to suicide from a state of calm and you can outline correlations that are well established versus ones that are emotional and quite flimsy on the evidence but given the way most people are receiving their information in modern times, and this doesn’t mean the solution is censorship, I’m not sufficiently moved to dismiss a significant correlation between hateful rhetoric and violence as I think a strong link could be established with proper research between violence and the reaction to it, the perception (true or false) that a contingent would approve of one’s violent behavior or be sympathetic because in these highly polarized times, they very well might.

Do you know who Marc Elias is? Tell me what he was up to prior to the election and tell me that was not shenanigans.